ANGLO-FRENCH FIRMNESS BOOSTS PEACE FORTUNES

London, England; Paris, France; Warsaw, Poland • August 28, 1939

Public opinion in Europe had shifted from dread of war and a longing for peace evident in the Czech Sudeten crisis of September 1938 to a fatalistic acceptance that war over Poland was now unavoidable. In Germany even Adolf Hitler’s political opponents assumed that if the Fuehrer attacked Poland he would have the majority of the population behind him. Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda organs blamed the intransigence of the Poles to negotiate changes to the Polish land corridor between West and East Prussia and the status of the ethnic German enclave of Danzig (modern Gdańsk) on alleged British and French policies aimed at “preventing Germany’s resurgence through encirclement.”

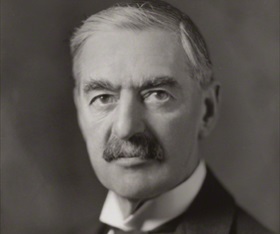

For their part British and French politicians were more confident that they could take their countries into war if pushed by Nazi aggression against democratic Poland. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and Premier Édouard Daladier both felt betrayed when Adolf Hitler occupied Germany’s southeastern neighbor, Czechoslovakia, in March 1939 in defiance of the 1938 Munich Agreement to which all 3 statesmen, plus Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, had been signatories.

On this date, August 28, 1939, both Chamberlain and Daladier believed that this year’s strategy of staring down rather than appeasing the aggressor had kept the door open to further negotiations in the Polish case now that the predicted invasion of Poland was a nonevent. (Their spy agencies and senior anti-Hitler German officers had supplied both senior statesmen with the German timetable for mobilization and invasion.) The French and British governments sensed that Hitler had “climbed down” from war, thereby materially strengthening their position, and that the Polish crisis had exposed chinks in German armor.

Among the chinks in German armor were rumored splits within Hitler’s Nazi Party and the German high command’s supposed rethinking of next steps—even the possibility of a military coup. The Poles were placing no bets on events outside their control. Earlier, on August 23, Warsaw ordered the mobilization of all army units in the Polish Corridor and much of Western Poland, a greater part of which had, prior to October 1918 and the birth of the Polish Republic, once belonged to Imperial Germany. The air force, antiaircraft defenses, and all senior staff units were also mobilized. Now on August 27 the remaining Polish reserve units were mobilized, and the following day measures were made for evacuating people from the western frontier to ensure that the area was ready for military action.

The British, after ordering the mobilization of 35,000 Territorial Army soldiers on this date, were taking no chances with their country’s major art treasures. Collections from the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Natural History Museum, and the Imperial War Museum began their evacuation to areas outside London and to the west of England. Other collections were crated and sent to stately manors for storage. Hospitals were cleared of nonessential cases, railway stations installed blue lights in anticipation of expected blackouts, and children in British cities were preparing for evacuation to the countryside beginning September 1. The watchword was, “Be Prepared.”

Players in the Drama Leading Up to the Invasion of Poland in 1939

|  |

Left: Convinced that he could appeal to the practical self-interest of European states to settle disputes among themselves, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain (1869–1940) is best remembered for appeasing Hitler. After Germany’s unilateral annexation of the Czech state in March 1939, Chamberlain reversed course and worked hard to obstruct Hitler’s designs on Poland. During the last week of August 1939, the British prime minister believed that a firm stance by him and French Premier Édouard Daladier to honor their countries’ treaty commitments to Poland would pay dividends by moving Hitler to the negotiating table, where a solution to the Polish question would then be guaranteed by an international settlement.

![]()

Right: French Premier Édouard Daladier (1884–1970) had no illusions about Hitler’s ultimate goals. A signatory himself to the ill-fated Munich Agreement, he told Chamberlain in 1938: “Today, it is the turn of Czechoslovakia. Tomorrow, it will be the turn of Poland.” He urged their two countries to stick together. If the two allies capitulated again to Hitler, he prophesied they would precipitate the war they wished to avoid. War came anyway.

|  |

Left: Chief of staff and de facto war minister under Hitler, Wilhelm Keitel (1882–1946) believed that the August 1939 German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact (Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact) militated against the prospects of a war with Poland turning into a world war. Wrong on so many other counts beginning on September 3, 1939, Keitel was tried by the victorious Allies at Nuremberg, sentenced to death, and hanged as a war criminal on October 16, 1946.

![]()

Right: A counterintelligence officer in the German Abwehr (German intelligence service) under Adm. Wilhelm Canaris, Hans Oster (1887–1945) was delighted to hear that Hitler had rescinded his order to march on Poland. “The Fuehrer is done for,” he predicted. “It is now merely a question of time and manner: how could this unmasked imposter be removed with the least trouble and the most elegance.” Both Oster and Canaris were hanged on Hitler’s orders after the discovery of their connection to the July 1944 bomb plot to kill Hitler at his East Prussia headquarters.

German and Soviet Invasion of Poland, September 1939, As Seen in Colorized German Newsreels

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click