AMERICANS ADVISED TO LEAVE JAPAN

Washington, D.C. · January 9, 1941

On this date in 1941 in Washington, D.C., the U.S. State Department advised American citizens to leave Japan. Two summers earlier the State Department had informed Japan that it would not renew the 1911 Treaty of Commerce and Navigation between the two countries, leaving the U.S. free in January 1940 to impose economic sanctions against the island nation as punishment for its 1931 invasion of Manchuria and its barbarous aggression (especially since 1937) in China. By 1939, the Japanese occupied Beijing, the Nationalist Chinese capital of Nanking (Nanjing), China’s major seaport Shanghai, and practically the entire Chinese coastline, as well as China’s major industrial areas. American aid to the beleaguered Chinese contributed to the rise of tensions between the U.S. and Japan, as well as the prohibition in mid-1940 to sell aviation gasoline, steel and iron scrap, and mechanical parts to Japan, which the Japanese were converting into war materiel.

In early 1941 the U.S. issued directives requiring export licenses for the shipment of copper, brass, bronze, zinc, nickel, potash, and the semi-manufactured products made from those materials. The action gave Washington further control over trade with Japan. In late July 1941, reacting to Japan’s announcement on July 25, 1941, of a protectorate over Vichy French Indochina (today’s Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia), the U.S. ended oil exports to Japan and froze Japanese assets totaling $130 million. Great Britain and many members of its Commonwealth followed suit and renounced all commercial agreements with Japan. Though their mother country had fallen victim to Nazi jackboots two months earlier, officials in the Dutch East Indies (today’s Indonesia) froze Japanese assets and refused to provide further oil shipments to Japan.

On July 26, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the U.S. Army Forces Far East to be formed in the Philippines under the command of 59-year-old Lt. Gen. Douglas MacArthur, who had been recalled to active duty the month before. On August 1 the U.S. Navy established a naval air station on Midway Island in the Central Pacific. A Marine Defense Battalion had already arrived in American Samoa in the South Pacific. Suddenly the January 9 State Department advisory to leave Japan took on a heightened urgency.

![]()

Storm Clouds Gather Over Southeast Asia: China vs. Japan vs. U.S.

|

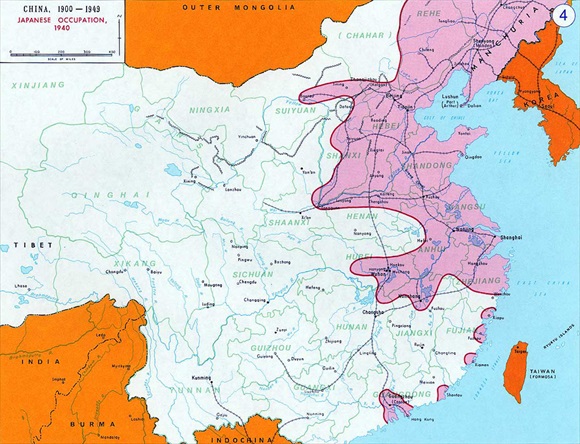

Above: Map of China, 1940, showing the extent of Japanese expansionism (in purple). Japan seized Taiwan in 1895, declared Korea an imperial protectorate in 1905, and invaded Manchuria (Manchukuo) in 1931.

|  |

Left: On November 27, 1940, retired Adm. Kichisaburō Nomura was sent as Japan’s ambassador to the United States. Throughout much of 1941, Ambassador Nomura negotiated with U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull in an attempt to prevent war from breaking out between Japan and the United States. The two men attempted to resolve issues, among them the Japanese conflict with China, the Japanese occupation of French Indochina, and the United States oil embargo against Japan. Nomura’s repeated pleas to his superiors in Tokyo to offer the Americans meaningful concessions were rejected by his government. On November 15, 1941, Nomura was joined by a “special envoy” to Washington, Saburō Kurusu, Japan’s ambassador to Nazi Germany from 1939 to November 1941. Hull and the two Japanese (Nomura on Hull’s right) are shown in this photograph taken in the days leading up to Pearl Harbor.

![]()

Right: Nomura (left) and Kurusu after meeting President Roosevelt at the White House. Secretary of State Hull had brought special envoy Kurusu to the White House to meet with Roosevelt after Kurusu had come with Tokyo’s last peace offer. When Kurusu reviewed Roosevelt’s November 26 demands for peace in Asia—namely, that Japan withdraw its troops from China and sever its ties with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy as a condition for peace—he replied: “If this is the attitude of the American government, I don’t see how an agreement is possible. Tokyo will throw up its hands at this.” On the afternoon of December 7, 1941 (Washington time), Kurusu delivered Japan’s reply to Roosevelt’s counter demands, breaking off relations and closing with the statement that “The immutable policy of Japan is to promote world peace.” Unaware of what had happened that morning at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii (though the president and Hull had been apprised), Kurusu and Nomura were questioned by news reporters as they left Hull’s office. “Is this your last conference?” one asked. An unsmiling Nomura had no answer. “Will the embassy issue a statement later?” asked another. Kurusu replied, “I don’t know.”

Japanese Aggression in China, 1931–1941

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click