ALLIES TRAP GERMAN ARMY IN FALAISE POCKET

Falaise, Northern France • August 18, 1944

Two and a half months had passed since the initial landings of U.S., British, and Canadian forces in Northern France (Operation Overlord). On the British flank the Canadian First Army, Second Division, II Corps entered Falaise on August 16, 1944 (see map below) and engaged the Germans in bitter street fighting. The next day II Corps completed the capture of the town. The 20‑mile/32‑km-long corridor through which units of the retreating German Seventh Army and Fifth Panzer Army could escape the Allies’ encirclement was squeezed to a minimum. On this date, August 18, 1944, between Falaise on the northeastern edge of the corridor and Argentan, the town that anchored the southeastern edge, II Corps’ Canadians and Poles and advance guards of Lt. Gen. George Patton’s newly activated (since August 1) U.S. Third Army, VI Corps moved to close the so-called Falaise Gap.

One hundred fifty thousand worn-down German soldiers in roughly 21 diminished formations ran the Allies’ gauntlet to escape annihilation in Normandy. Thirty thousand, perhaps as many as fifty thousand, broke through the 10‑mile/16‑km wide Falaise Gap to form a new German line in front of the Allied advance. But the gauntlet to relative safety had been a bloody meat grinder, the Allies relying chiefly on relentless artillery (as many as 3,000 pieces) and airpower (1,500–3,000 sorties per day) to blast the fugitive enemy and their equipment to smithereens so as to avoid, according to one explanation, the calamity of commingling Canadian and U.S. ground forces accidentally firing at each other. Thus, German dead and wounded numbered at least 30,000; furthermore, 350 tanks and armored vehicles and nearly 1,000 artillery pieces of every type were lost. Fifty thousand shell-shocked and exhausted fugitives were taken captive. Remarkably, a further 240,000 men and 25,000 vehicles crossed to the north bank of the River Seine between August 19 and 31, fleeing eastwards toward Germany and the Rhine.

Called to Berlin to explain himself to Adolf Hitler, Commander-in-Chief in the West Field Marshal Guenther von Kluge—his career laden with successes but marred by his involvement in the July 20 attempt on Hitler’s life—committed suicide en route. Kluge had been relieved of his command on August 17 by Hitler and temporarily replaced with the politically reliable Field Marshal Walter Model, nicknamed the “Fuehrer’s Fireman.” Model himself was a suicide 8 months later (April 21, 1945) after having been publicly denounced as a traitor to the Reich the day before for dissolving his command, Army Group B (Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s old command), which was trapped by 2 American armies in the Ruhr, Germany’s industrial heartland.

By the end of August 1944 the Falaise Pocket had been cleansed of the enemy. In the Battle of Normandy (June 6, 1944, to August 31, 1944) the Germans had suffered upwards of 530,000 casualties, including 210,000 prisoners of war and the loss of over 2,100 precious aircraft and between 1,500 and 2,400 tanks and self-propelled guns. Allied casualties were less than half that and their equipment losses were more easily replaced. French civilian casualties during the pre-invasion softening up and the Normandy invasion numbered between 25,000 and 39,000. The Allies’ chase now shifted into overdrive. The Germans abandoned the French capital, Paris, without a fight. On August 25 a mixed U.S.-French force landed in the south of France (Operation Dragoon), opening a second invasion front, this in the Rhône River valley. For his part Patton advanced into Lorraine in Eastern France while Gen. Bernard Law Montgomery took the Belgian capital, Brussels, and the massive inland port of Antwerp. When on September 1 Allied Supreme Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, newly taking up residence in France, assumed command of the invasion ground forces hitherto under Montgomery’s command, it appeared that victory in Europe would be won before year’s end.

The Falaise Pocket, Cauldron of Death

|

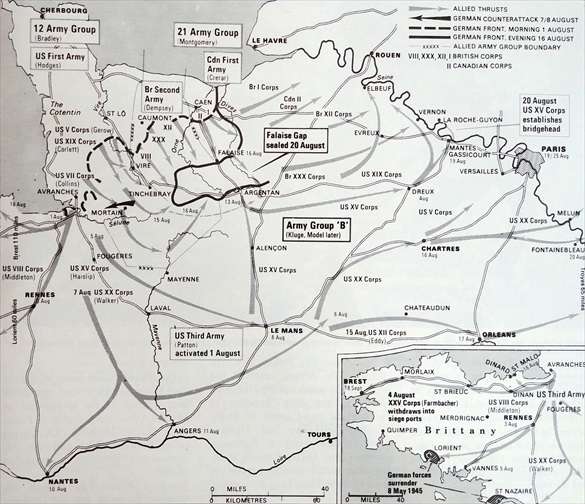

Above: Map of Northern France and the Falaise Pocket and Gap, August 16‑20, 1944. Gen. Montgomery’s Canadians and Poles, having taken the tactically important town of Falaise, almost linked up with Lt. Gen. George Patton’s Third Army at Argentan. Enough of a gap between the 2 French towns was left for Field Marshals Guenther von Kluge and his successor Walter Model to extricate some 30,000 men who had been routed from Normandy. Conservative estimates put the number of Germans killed in the pocket at 10,000 and the captured at 50,000, although some estimates put total German losses (killed and captured) as high as 200,000. The Battle of the Falaise Pocket, known by Germans as the Falaise Cauldron (Kessel von Falaise), took place between August 12 and 21, 1944. It was the largest encirclement on the Western Front during World War II (150,000 men) and is considered the decisive engagement in the Battle of Normandy (June 6 to August 30, 1944), notwithstanding that upwards of 100,000 Wehrmacht troops escaped a trap that should have ensnared them. Map source: Cesare Salmaggi and Alfredo Pallavisini, 2194 Days of War: An Illustrated Chronology of the Second World War, 1988 ed., p. 575.

|  |

Left: Covering the withdrawal of German forces through a gap at Falaise, artillerymen of the 12th SS Panzer Division “Hitler Jugend” service their weapon. The Germans held desperately to the shoulders of the Falaise Pocket and thousands managed to avoid capture.

![]()

Right: An American antitank company of the untested 317th Infantry Regiment, 80th “Blue Ridge” Infantry Division, U.S. Third Army, fires it 57 mm/2.24 in. antitank gun at a distant target during action at Falaise. The company was in position to fire on the Germans as they retreated east from the war-ravaged town of Argentan. The “Blue Ridgers” captured almost 12,000 prisoners and destroyed over 125 tanks during their time in France.

|  |

Left: Germans surrendering to Canadian troops in St.-Lambert-sur-Dives, August 19, 1944, in the closing stages of the Battle of Normandy. The day before the Canadian 4th Armored Division killed, captured, and wounded over 3,000 enemy soldiers during their attack on St.-Lambert-sur-Dives. The captives in this photo were likely members of the 2nd and 9th SS Panzer Divisions, employed in a last-ditch effort by Field Marshal Model to keep 2 remaining escape routes open for Germans trapped in the Falaise Pocket. At midnight August 20 the exit from the pocket was finally sealed at Chambois, a town straddling the Falaise Gap halfway between Falaise and Argentan and the meet-up point between Allied armies. At noon on August 21, a German general outside the pocket reported that the arrival of fugitives escaping the pocket had stopped completely. Late that afternoon or early evening German infantrymen, in a climactic suicide attack, ran straight at a Polish machine gun battery. Many more, however, had grown weary after harrowing days of flight and carnage and chose to surrender.

![]()

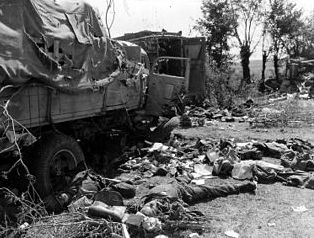

Right: Seen in this photograph taken around August 20 or thereabouts German dead litter an ambushed convoy in Chambois. “The floor of the valley was seen to be alive,” wrote one Allied eyewitness, “. . . men marching, cycling and running, columns of horse-drawn transport, motor transport . . . It was a gunners’ paradise and everybody took advantage of it . . . Away on our left was the famous killing ground, and all day the roar of Typhoons [British fighter-bombers] went on and fresh columns of smoke obscured the horizon . . . the whole miniature picture of an army in rout.” Quoted in Max Hastings, Inferno: The World at War, 1939-1945, pp. 537–38. Two days after the gap was closed, Eisenhower visited the Dante-esque killing ground, writing that it was literally possible to walk for hundreds of yards at a time stepping on nothing but dead and decaying flesh.

Contemporary Newsreel Account: Encirclement of the German Seventh Army in Falaise Pocket

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click