ALLIES SET UP RHINE MEADOW CAMPS FOR GERMAN PRISONERS

Rhine Meadow Camps, German Rhineland • April 17, 1945

By this date in 1945 and over the next 2 months, American, British, and French armies established 19 Rhine Meadow camps (German, Rheinwiesenlager) principally on the west bank of the Rhine River in the German states of North-Rhine Westphalia and Rheinland-Pfalz (Rhineland-Palatinate) (see map below). The Rhineland camps were officially part of the Allies’ Prisoner of War Temporary Enclosures (PWTE) and held between 1 million and 1.9 million Wehrmacht (German military) and “suspicious civilian” (verdaechtige Zivilpersonen) prisoners who were captured or surrendered by the end of May 1945. The prisoners were classified under a new designation invented the previous month, Disarmed Enemy Forces (U.S.) or Surrendered Enemy Personnel (British) (DEFs/SEPs) instead of prisoners of war (POWs) as codified in the 1929 Geneva Convention.

Until New Year’s 1945, German POWs were typically transported across the Channel or the Atlantic to Great Britain, Canada, and the United States. But after 250,000 Germans had been swept up in the failed German Ardennes offensive, aka Battle of the Bulge (December 16, 1944 to January 25, 1945), and 325,000 after the Allies’ destruction of Germany’s Ruhr Basin (April 1–20, 1945), there were now more than 3.4 million German prisoners in Allied custody. Envisioning the imminent collapse of the Wehrmacht and the Nazi Third Reich, the Western Allies saw the logic in keeping their recent captives at home as it were.

The 19 Rhine Meadow camps began their existence in open farmlands close to German villages served by a rail line; buildings bordering the farmlands were converted into administrative offices, kitchens, and infirmaries. A few of the camps remained operational into September 1945. Some camps were enormous and subdivided into smaller enclosures for 5,000 to 10,000 people. Camps were segregated by gender, military affiliation, and date of capture: e.g., POWs captured before Germany’s capitulation on May 8, 1945; DEFs/SEPs without the status of POW who surrendered after May 8; nurses; Waffen SS; and high-profile Nazis. Teenage and elderly Volkssturm (home guard) soldiers were disarmed and released after a few days; same for women and political types who were “beyond reproach” (politisch unverdaechtig). Military equipment like shovels, tents, and blankets was confiscated. To create shelters and sleeping places for themselves internees used helmets, ration cans, and fingers to dig holes in the ground.

Interestingly, the 40,000-strong U.S. 106th Infantry Division had overall responsibility for the camps, but the division placed internal camp administration in the hands of prisoners: camp managers, armed guards, doctors, cooks, work detachments were posts assumed by Germans themselves.

As if postwar German-run prison camps weren’t controversial enough, the nature and number of camp deaths were. The estimated deaths in the Rhine Meadow camps between April and September 1945 range from 3,000 to 10,000. Official U.S. government statistics on the death tolls range between 3,000 and 6,000, most occurring in the first 2 months of the camps’ existence. A variety of German sources place the lowest figure at 8,000 dead and the highest at 40,000. The West German Maschke Commission (1962–1974) scientifically and extensively investigated the history of German prisoners of war on behalf of the Federal Ministry for Expellees, Refugees, and War Victims. From church records and eyewitness accounts commission members tabulated 4,537 deaths in the 6 most-notorious Rhine Meadow camps, which held 557,000 prisoners from April to July 1945, and in the remaining camps just 774 deaths; commissioners reckoned, however, that the true death count for the 6 camps might be twice as high. A Canadian novelist, James Bacque, who neither examined the Maschke collection nor could read German, posits an absurdly inflated 790,000 to 1,000,000 camp deaths. Bacque’s 1989 revisionist book, Other Losses, is hotly contested by U.S. and German historians.

Rhine Meadow Camps, German Rhineland, April to September 1945

|

Above: This map of the Rhineland shows the location of 19 Rhine Meadow camps (German, Rheinwiesenlager). The camps were officially named Prisoner of War Temporary Enclosures (PWTEs). Situated in the north were three British-run PWTEs, Buederich, Rheinberg, and Wickrathberg. From Remagen and moving south, the camps were run by the U.S. and, after June 10, 1945, France, the date the Americans transferred ownership of their camps to France at the latter’s request. The French government under Gen. Charles de Gaulle wanted 1.75 million prisoners for forced labor in France to rebuild that country’s infrastructure damaged by 4 years of combat on its soil. Eight camps were emptied of some 182,400 prisoners and transported to France as a kind of “labor reparations.” The British, who controlled the Buederich and Rheinberg camps, handed de Gaulle all prisoners fit for work and sent the rest on their way, closing their camps. By the end of September, nearly all Rhine Meadow camps were shuttered. Only the Bretzenheim camp, aka “Field of Misery” (German, Feld des Jammers), remained open until 1948. It was needed as a transit camp for German prisoners released from work in France.

|  |

Left: German soldiers in this photo were captured after the fall of Aachen in October 1944 and given POW status; they are unlikely to have been placed in a Rhine Meadow camp the following year. Under the 1929 Geneva Convention, which governed the humanitarian treatment of prisoners of war, POWs were to be sent home within months of the end of the war. But their treatment necessarily required a German government able to negotiate with the International Committee of the Red Cross. Allied governments refused to recognize the validity of the Nazi regime of Grand Adm. Karl Doenitz, who, after Adolf Hitler’s suicide on April 30, 1945, governed what remained of the Third Reich from Flensburg near the Danish border. Doenitz and his cabinet were arrested on May 23, 1945, by order of Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). The Doenitz regime was dissolved the same day. A 4‑power document, the Declaration Regarding the Defeat of Germany, formally abolished any German governance over the vanquished nation and gave the U.S., Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union legal cover for assuming political control of Germany.

![]()

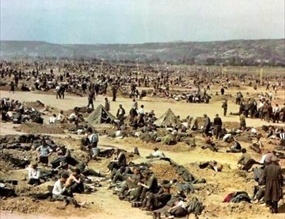

Right: Aerial view of an unidentified Rhine Meadow camp. The Allies incarcerated between 1 million and 1.9 million enemy combatants during the 6‑month existence of the Rhineland camps. Many of the combatants arrived at the camps sick, wounded, or malnourished due to Nazi Germany’s economic collapse in the last months of war. German rail transportation and food factories had been heavily bombed in the Allies’ campaign to hasten the end the war. The average German civilian at the time was reduced to living on 1,000 calories per day, a starvation diet. It’s no wonder that malnutrition and disease spread through these prison camps in the first 2–3 months of their existence.

|  |

Left: Prisoner of War Temporary Enclosure at Sinzig, Germany, probably May 12, 1945. On that date, 116,000 German prisoners of war were held there; the rated capacity was 100,000. Prisoners were kept in a barbed wire-fenced open field with little or no shelter. Sinzig PWTE and the neighboring camp at Remagen accounted for half the prisoners held in the Rhine Meadow camps. Sinzig was one of the six Rhineland camps with the highest mortality rates.

![]()

Right: Lacking shovels, spades, or trowels—anything of that kind having been confiscated by camp authorities—prisoners dug holes in the ground for shelter and a place to sleep. During rainstorms these holes filled with water, making them inhabitable. Many inmates died from starvation, dehydration, and exposure to the elements because no structures were built inside the prison enclosures.

The Rhine Meadow Camps: What Really Happened

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click