ALLIES SEIZE RENOWNED BENEDICTINE ABBEY

Cassino, Italy • May 18, 1944

On February 15, 1944, British Gen. Harold Alexander, commander-in-chief of all Allied armies in Italy, ordered the aerial bombing of the ancient Benedictine abbey towering over the pastoral town of Cassino on the banks of the Rapido (or Gari) River in Italy. Earlier in January, British, American, and French troops had made a series of attacks on the main German defenses in mainland Italy, the Gustav Line—this around the town of Cassino. Sometimes called the First Battle of Cassino, these attacks produced only limited gains.

The February 15 bombing of the iconic mountaintop abbey of Monte Cassino (Operation Avenger), which Alexander wrongly thought was being used by the Germans as an observation post to direct artillery fire on his troops below, was part of a broader effort by soldiers from more than a dozen Allied nations to break through German lines and open 1 of only 2 roads connecting Allied-held Southern Italy with German-held Rome. The Germans had built sufficient observation and defensive positions up and down the mountain side to within 200 yards/183 meters of the abbey. An enemy observation post at the summit conferred no additional advantage, but sadly the Allies didn’t know that. Monte Cassino’s destruction, Alexander confessed later, was “necessary more for the effect it would have on the morale of the attackers than for purely material reasons.”

Surprisingly, a full day passed before the initial air strike by 229 U.S. heavy and medium bombers, dropping 1,150 tons of high explosives and incendiary bombs on the historic abbey, was followed by a timid ground attack (a single British infantry company) up the mountain’s flinty slopes. By then the Germans had had the time to convert the ruins and the thick-walled foundations of the monastery into an impregnable, 7‑acre/2.8‑hectare fortress from which they could direct artillery rounds against anyone sent against them.

The Allies’ controversial destruction of the abbey, fortunately empty of its movable art and world-renowned library, and the death of more than one hundred Italian refugees who had sought sanctuary within its walls were a huge propaganda coup for the Nazis, and Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda Joseph Goebbels played up the destruction and deaths for all their worth.

More air and especially costly ground assaults would take place over the next 4 months. The seemingly interminable Cassino meatgrinder caused British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to bark at Gen. Alexander: “I wish you would explain to me why this passage by Cassino [and] Monastery Hill is the only place which you must keep butting at. About 5 or 6 divisions have been worn out going into those jaws.” Finally, on this date, May 18, 1944, the Allies, after suffering approximately 55,000 casualties (the Germans incurred at least 20,000 casualties), were able to raise their flag—an improvised Polish regimental flag—over the rubble of the abbey as well as over 30 wounded soldiers left by their comrades as the Germans abandoned the western half of the Gustav Line for new defensive positions further north up the Italian boot.

Battle of Monte Cassino, January 17 to May 18, 1944

|  |

Left: Ruins of the town of Cassino after the 4-month battle, longest land battle fought in Western Europe in World War II. In. In the background are the grim ruins of the Abbey of Monte Cassino. The landmark abbey lay just over 1 mile/1.6 kilometers to the west of the town at an elevation of 1,700 ft./518 m and had a commanding view of the Liri and Rapido valleys, Allied gateways to German-held Rome. The 4 battles to take the town and abbey cost the lives of more than 14,000 men from a dozen nations. Total Allied casualties spanning the period of the 4 Cassino battles and the Anzio campaign with the subsequent capture of Rome by Lt. Gen. Mark Clark’s Fifth Army on June 5, 1944, were over 105,000. Clark, who served under Alexander, recalled: “The battle for Cassino was the most grueling, the most harrowing, and in one respect the most tragic, of any phase of the war in Italy.”

![]()

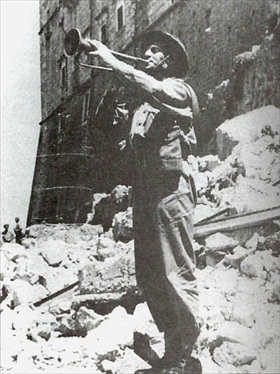

Right: A Polish bugler plays the medieval 5-note Polish military signal, the Hejnał Mariacki (also called the Kraków Anthem), at the foot of Monte Cassino Abbey, announcing the Allied victory on May 18, 1944. Elements of the Polish II Corps were the first among the Allied units to reach Monte Cassino’s summit. It was also the first time since September 1939, when their country was subjugated by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, that Polish armed forces outside Poland itself battled the hated Germans face to face. The Polish II Corps lost 50 men a day—about 20 percent of its strength—by the end of the Cassino campaign but gave no quarter, particularly after the Germans had crucified 2 captured Polish officer cadets with barbed wire and nails. Field Marshall Bernard Law Montgomery praised the Polish soldiers for their panache and skill, saying, “Only the finest troops could have taken the well-prepared and long-defended fortress.” And Free French leader Gen. Charles de Gaulle told the press, “The Polish Corps lavished its bravery in the service of its honor.” During 1944–1945 in Italy the Polish II Corps consistently fought with distinction and incurred 11,379 casualties: 2,301 killed in action, 8,543 wounded, and 535 missing.

|  |

Left: Monte Cassino in ruins, February 1944. St. Benedict of Nursia established his first monastery, the source of the Benedictine Order, here around AD 529 and over time it become a repository of valuable art works and a world-renowned library.

![]()

Right: The restored Abbey of Monte Cassino sits on rocky hill about 80 miles/129 kilometers southeast of Rome. It is still one of the most famous monasteries in Christendom.

|  |

Left: Men of the German Tenth Army, 1st Fallschirmjaeger (Parachute) Division used the grounds in and around the ruined abbey to their advantage to rain down artillery, mortar, and machine gun fire on those wanting to work their way to the summit.

![]()

Right: Captured German paratroopers. About 100 surrendered to the British. Others sought to break out as the Allies closed in on the makeshift German fortress. Joseph Goebbels’ Propaganda Ministry glorified the dedication of the fortress defenders without mentioning that the abbey had fallen to the Allies.

Timeline: The Hellish Battle of Monte Cassino, Italy, January–May 1944

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click