ALLIES SEIZE LUDENDORFF BRIDGE AT REMAGEN, CROSS RHINE

Remagen, Germany • March 7, 1945

By March 1945 the German Wehrmacht (armed forces) was reeling from horrendous personnel and equipment losses incurred during the Battle of the Bulge (December 16, 1944, to January 25, 1945) in the Ardennes Forest, which lay mostly in Belgium and Luxembourg. The military momentum now clearly favored the Western Allies as additional thrusts by Gen. Omar Bradley’s U.S. 12th Army Group and Field Marshal Sir Bernard Law Montgomery’s 21st Army Group in January and February proved, nudging the Western Front eastward toward the Rhine River, Germany’s natural barrier to invasion from the west. Broad and swiftly flowing, the blue-green Rhine was a formidable obstacle to hostile armies, and the few bridges that crossed it were choke points that restricted the size and speed of invaders. The Wehrmacht, on the defensive and capitalizing on knowing the lay of the land, began demolishing the Rhine bridges as their armies retreated east across the Rhine to the imagined safety of the fatherland.

German Army Group B commander Field Marshal Walter Model wagered that the main Allied thrust east across the Rhine would be against Bonn, 15 miles/24 km north of the small town of Remagen and where the Rhine Valley terrain was open to an armored advance. Thus, Model left Remagen and its Rhine crossing, the Ludendorff Railroad Bridge, which abutted a 600‑ft‑/183‑m‑high cliff and nearly quarter-mile-long tunnel at its eastern end, in the hands of a motley set of defenders: 100 regular infantrymen and another 140 convalescent soldiers, the bridge’s principal defenders; a few, mostly middle-age engineers; some Russian “volunteers” who had been captured on the Eastern Front; and the local Volkssturm militia, members of which consisted of teens and older men considered unfit for regular combat duties. The engineer unit was tasked with preparing the Rhine bridges for demolition and operating ferries to help evacuate troops from the west bank of the Rhine to the east.

In the foggy morning hours on this date, March 7, 1945, leading elements of the U.S. First Army, III Corps, 9th Armored Division reached a hilltop clearing overlooking the Rhine bridge at Remagen (see map below). To the soldiers’ amazement they could see a long gray line of German troops and vehicles moving across wood planking on the Ludendorff Rail Bridge, the only still-usable bridge over the Rhine within immediate American reach. By 3 p.m. the Americans had swept most of the enemy from the town and were making their way to the bridge, where they could see Germans making haste to detonate explosives to destroy the bridge. Indeed, a demolition charge on the western approach ramp to the bridge was set off, creating a large crater that prevented tanks from crossing the bridge, and second demolition charge two-thirds of the way across the bridge’s 1,200‑ft/367‑m-span sent wood planks and metal flying but did not collapse the bridge. Elements of an armored infantry battalion, the 27th, arrived to force the enemy from the eastern end. Two 9th Armored Engineer Battalions also swung into action. Three gutsy combat engineers dashed onto the bridge, dodging intense automatic weapons fire, to cut the demolition wires, preventing the Germans from touching off explosive charges planted on the crossbeams underneath.

While this was going on a private led a small group of U.S. infantrymen across the bridge to the east side; they were followed by 120 more men. The bridge’s defenders and German civilians who huddled in the Erpeler Ley railroad tunnel surrendered. The antiaircraft battery above the tunnel was silenced. The Ludendorff Bridge, the town of Remagen, and the approach to the Ruhr District in Germany’s industrial heartland were now in American hands. Two months later, on May 7, 1945, the German High Command grudgingly accepted the inevitable defeat of Nazi Germany by signing the “Act of Military Surrender” document at Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Supreme Allied Headquarters in Reims, France, bringing the European phase of World War II to an end.

Breakthrough at Remagen: First Allied Crossing of the Rhine

|

Above: Using a broad-front strategy, the Allied 12th and 21st Army Groups approached the Rhine River in early spring 1945. The 9th Armored Division used the Ludendorff Railroad Bridge to cross the Rhine at Remagen on March 7, 1945, while elements of George S. Patton’s U.S. Third Army crossed at Oppenheim south of Mainz on the night of March 22/23, and elements of Montgomery’s 21st Army Group at Wesel and Rees north of Duesseldorf the next day.

|  |

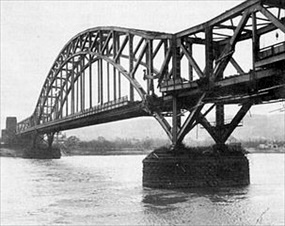

Left: The Germans had wired the Ludendorff Railroad Bridge at Remagen with about 2,800 kg/6,200 lb of demolition charges. Most of the charges (2,000 kg/4,409 lb of explosives) were placed on the 2 stone piers in the river that carried the load of the 1,200 ft/367 m bridge span. Two charges of 300 kg/660 lb each were attached to the girders connecting the bridge to the piers. The charges were attached to an electric-ignition fuse system and connected by electrical cables running through pipes to a control circuit located in the entrance to the tunnel under Erpeler Ley, the 600 ft/183 m rock that overlooks the Rhine River valley opposite Remagen. When the Germans tried to blow up the bridge, only a portion of the explosives detonated. Damage was thus limited to the eastern pedestrian catwalk and a 30 ft/9.1 m section of the main truss supporting the northern side of the bridge, as shown in this photo.

![]()

Right: The U.S. Eighth Air Force had repeatedly tried destroying the 26‑year-old Ludendorff Bridge to disrupt German efforts to reinforce their troops in the west: on October 9, December 28–31, 1944, and multiple times in January, February, and on March 5, 1945, 2 days before the bridge’s capture. Prior to capture, it was a case of the Germans quickly repairing damage to the bridge and aerial mission failure on the part of the Eighth Air Force. In this photo taken 4 hours before the bridge collapsed without warning on the afternoon of March 17, combat engineers are busy repairing steel supports beneath the road surface. Shortly after the bridge was seized, the Germans lobbed artillery and 540 mm mortar shells, sent aircraft (including the new Me 262 fighter jet and the new Arado Ar 234 jet bomber, which carried 1,000 kg/2,200 lb bombs), and even fired 11 or so V‑2 rockets to demolish the bridge, to no avail, although the V‑2s came dangerously close to hitting it. (Most landed within several miles/kilometers of the bridge, destroying several farms and killing civilians and farm animals.) When the weather improved American P‑38 twin-engine Lightnings flew continuous air cover of the bridge. At the same time, 3 LCVPs (Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel) began patrolling upriver and dropping depth charges at intervals to interdict enemy midget submarines and combat swimmers.

|  |

Left: In the 10 days before its collapse, over 25,000 troops from 5 U.S. divisions, like these shown here from the 9th Armored Division’s 47th Infantry Regiment, together with thousands of vehicles and tons of supplies had crossed the Ludendorff Bridge and 3 newly built tactical bridges above and below this ancient, Roman-built resort town on the fabled Rhine. In the serendipitous Battle of Remagen (March 7–25, 1945) Bradley’s 12th Army Group had managed to create a well-established bridgehead almost 25-miles//40-kilometers-long, extending from Bonn 15 miles/24 kilometers north of Remagen almost to Koblenz 20 miles/32 kilometers to the south, and just over 6 to 9 miles/9.6 to 14 kilometers deep. The area U.S. forces streamed into was virtually undefended because German Field Marshal Model miscalculated, thinking the mountainous country east of Remagen would dissuade the enemy from crossing there. Ironically, the Remagen bridgehead became, in the words of Army Chief of Staff George Marshall, “a springboard for the final offensive to come.”

![]()

Right: The twisted steel ruins of the Ludendorff Railroad Bridge as a backdrop, a U.S. Army truck crosses the Rhine River on a temporary pontoon bridge. By March 20 soldiers from an engineer combat battalion and a light pontoon company had replaced the pontoon bridge with a floating Bailey Bridge to help carry critical traffic to the Rhine’s east bank. A 2‑way Bailey Bridge on barges was built across the Rhine downstream at Bonn. Additional tactical bridges were built on the Rhine north and south of Remagen. Augmenting cross-river traffic were LCVPs (Landing Craft Vehicle, Personnel), 6‑wheel-drive amphibious DUKWs, and ferries. These measures took up the burden of moving Allied soldiers and equipment across the Rhine into the German heartland.

|  |

Above: Rescuers and medics wait for the casualties after the collapse of the Ludendorff Bridge into the Rhine on March 17, 1945. Seven soldiers were killed in the accident, 23 went missing and presumed drowned in the swift-flowing, icy water, and 3 later died from injuries; 63 others were injured. About 200 engineers and welders were working on the span when it fell. The center portion of bridge suddenly tipped into the Rhine, and the 2 end sections keeled off their stone piers. In the photo on the right an injured combat engineer is maneuvered through twisted wreckage and placed on a litter for transport to a hospital.

Contemporary Footage of Rhine River Crossings (Skip first 3:40 minutes for Ludendorff Bridge Collapse and Battle of Remagen)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click