ALLIES PLOT TO RETAKE BURMA, SUPPLY CHINA BY ROAD AND AIR

New Delhi, India · February 1, 1943

On this date in 1943 in New Delhi, delegates from Great Britain, the U.S., and China opened a conference to develop a campaign plan (codenamed Anakim) for the reconquest of Burma (also called Myanmar), then a British colony, and to reopen the land supply route to China. The Burmese capital Rangoon (now Yangon) had succumbed to Japanese invaders on March 8, 1942, nearly 7 weeks after the Japanese had crossed into Burma from Thailand. After taking the Burmese capital and seaport, more enemy troops arrived to push the remaining British forces into Eastern India and to threaten that British colony.

That August the Japanese asked Burmese nationalist Ba Maw, a Catholic, a lawyer, and politician whom the British authorities had once jailed, to head a provisional civilian administration reporting to the Japanese military. The next year, on August 1, 1943, the Japanese declared Burma nominally independent and installed a puppet government headed by the same Ba Maw. The new state quickly declared war on Great Britain and the United States.

The 717-mile/1,154-kilometer-long Burma Road, which 200,000 Burmese and Chinese laborers had built across Northern Burma during the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937–1938, funneled supplies from the Burma coast to Chiang Kai-shek’s Chinese Nationalists until the Japanese overran Burma in March 1942. Determined to keep China in the war and pressure on the Japanese, the Allies were forced to supply the Nationalists by air, flying day-and-night missions to Kunming in China from airfields in Eastern India over the Himalayan uplift known as the “Hump.” The 500‑mile/805‑kilometer-long India-China Ferry was also known as the “aluminum trail” on account of the more than 1,600 airmen and 640 transport planes lost in the mountains or in the jungles on either side due to bad weather, Japanese fighters, accidents, and mechanical failures. (Almost 1,200 men were fortunate to be rescued or walked out to safety.) Meanwhile, the Burma Road would remain shut until January 28, 1945, 3 months before British, Indian, and other Commonwealth troops expelled the Japanese from Rangoon on May 3, 1945.

Taking and holding Burma proved costly in Japanese lives. Sixty percent of Japanese troops died during the Burma campaign, mostly from tropical diseases. The equivalent figure for the Allies was about 10 percent, including those who perished as prisoners of war.

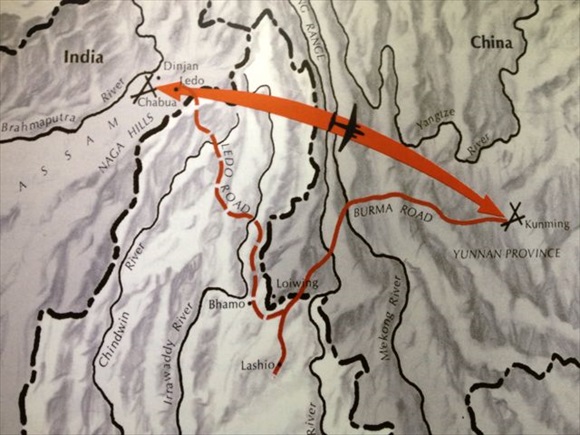

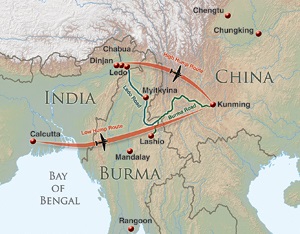

Supply Routes Between India and China: The Ledo and Burma Roads and the Air Bridge Over the “Hump”

|

Above: Japanese forces held all important points in Eastern China, including cities, railways, rivers, and ports. Land-based transport from the Burmese port of Rangoon to Lashio in Northern Burma, and from there over the Burma Road to Kunming, China, emerged as the principal means of delivering war materials, medicines, and other supplies to the beleaguered Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek during the initial years of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945). After the Japanese seized most of Burma in the first half of 1942, air convoys from India over the “hump” formed by the Himalaya Mountains, the highest mountains in the world, replaced land convoys.

|  |

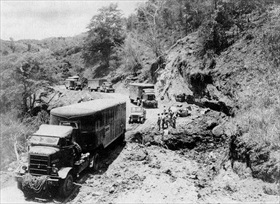

Left: The Burma Road was largely built by the Chinese themselves—160,000 workers using mostly hand tools to carve a 700‑mile/1,127‑kilometer-long road through the mountains of Western Yunnan to reach the Northern Burmese railhead at Lashio near the Chinese border. Before the Japanese conquest of Burma, war materiel and munitions passed from the port at Rangoon to Lashio, and from there across the Himalaya Mountains to Kunming, China. From Kunming supplies were transported to Chongqing (Chungking), the Nationalist government’s southwestern base and wartime capital.

Right: Another road used during the war was originally built by the British and Indians, starting in the 1920s, from Ledo in Assam over the mountains toward Lashio, 465 miles/724 kilometers to the south. Beginning in 1942 the Ledo Road (sometimes appearing on maps as the “Stillwell Road”) was heavily upgraded by U.S. forces. It was finished in January 1945. The first American convoy of 113 vehicles using the Ledo Road reached Kunming, 1,100 miles/1,770 kilometers from the starting point, on February 4, 1945. Over the next 7 months, 35,000 tons of supplies moved over the Burma Road in 5,000 vehicles.

|  |

Left: The Burma Road from Lashio to Kunming consisted of hairpin bends winding through mountain passes. The hair-raising “24 Turns,” often mistaken for a segment of the Burma Road, is actually beyond Kunming in the Chinese province of Guizhou.

![]()

Right: Air transports from India became the chief means of delivering supplies to the Chinese. Regular operations over the Hump began in May 1942 with 27 aircraft, mostly Douglas C‑47 Skytrains. Over time C‑47s were augmented by Curtis C‑46 Commandos, 4‑engine Douglas C‑54 Sky‑masters based in Calcutta (today’s Kolkata), and accident-prone Consolidated C‑87 Liberator Expresses. Even B‑24 Liberators, no longer needed in their primary bombing mission, were assigned as cargo haulers. Air transports flew through mountain passes that were 14,000 ft/4,267 m high, flanked by peaks rising to 16,500 ft/5,029 m. Elevations were lower at the southern end—the so-called “Low Hump”—but patrols by Japanese fighters forced most flights farther north until late in the war. Flying time was 4–6 hours, depending on the weather. The airlift ultimately operated from 13 bases in India. In China there were 6 bases, with the main terminus at Kunming, which became one of the busiest airports in the world.

|  |

Above: In the left frame, Douglas C-47s line an airstrip in the China-Burma-India Theater in 1945. By July 1945, on average 332 airplanes a day flew over the Hump (right frame), a far cry from the hard-pressed 62 on the route in January 1943. During its 42‑month history, the Hump transport fleet carried 650,000 tons of gasoline, supplies, and men to China, more than half of that total in the first 9 months of 1945. Military commanders considered flights over the Hump to be more hazardous than bombing missions over Europe. For its efforts and sacrifices, the India-China Wing of the Air Transport Command was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation on January 29, 1944, the first such award made to a noncombat organization.

U.S. Army Signal Corps: Building the Stilwell (Ledo) Road, Flying the “Hump,” and the Allies’ Burma Campaign

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click