ALLIES DISRUPT GERMAN DEFENSES IN FRANCE

London, England • June 1, 1944

In June 1942 members of the French Resistance provided British intelligence with a copy of the top-secret blueprint of portions of Adolf Hitler’s Atlantic Wall—part of the defenses against the anticipated Allied invasion of Western Europe. The map had been spirited from the office of the German public works bureau that was building the coastal defenses, and it revealed the strong and the weak points along the entire Northwestern French coast of Normandy, from Cherbourg in the west almost to Le Havre in the east.

The French Resistance continued to pass the Allies detailed information about the Normandy invasion area (gun emplacements and caliber, real and fake minefields, gaps in German flak defenses, etc.) right up to D-Day—information provided in part by some of the thousands of French laborers, foreigners who had been pressed into forced labor, and Italian POWs Field Marshal Erwin Rommel (he of Afrika Korps fame) was using to build stronger coastal defenses, plant millions of landmines (6 million in Northern France alone) and a variety of shallow-sea naval mines, flood large areas behind the flat beaches to drown Allied paratroopers, and drive long anti-airborne stakes called “Rommel’s asparagus” into open fields to thwart the safe landing of Allied troop gliders.

In advance of Operation Overlord, the codename for the June 1944 Normandy landings, Allied aircraft began pounding synthetic oil plants in Germany, which reduced the Luftwaffe’s fuel supply by nearly 70 percent between April and this date, June 1, 1944. Allied intelligence estimated that the enemy could lay hands on 2 million freight cars to move troops and supplies to the invasion front. So, to prevent the Germans from deploying, reinforcing, and resupplying their beachhead defenders, Allied aircraft heavily bombed and cratered French and Belgian highways, tunnels, canals, river crossings, and railroad yards, usually in daylight. In Operation Chattanooga Choo-Choo (May 20–28, 1944) Anglo-American fighter bombers strafed and destroyed French, Belgian, and German trains virtually with impunity. German air bases and coastal batteries were bombed up and down the English Channel. This forced some guns, for example the 6 155 mm artillery pieces at Pointe du Hoc that directly threatened the Allied amphibious armada and the 2 invasion beaches in the American sector, to be covertly moved inland, much to the surprise of U.S. Army Rangers who on D‑Day scaled the treacherous cliffs at Omaha Beach. Between April 1 and June 6 the Allies flew 200,000 bombing sorties over Northern France, averaging one ton of bombs dropped for every sortie. Nearly 2,000 aircraft were lost in these sorties.

Heavy too were the civilian casualties caused by these air raids, as well as from sabotage by Resistance fighters on the ground, particularly by Résistance Fer, the organization of French railwaymen: over 12,000 people lost their lives. (The Germans were quick with reprisals, executing several hundred cheminots, as the French railwaymen were known, and deporting another 3,000 to German camps.) But 80 classification/marshaling yards and 1,500 locomotives were put out of commission, along with miles/kilometers of railroad tracks (950 cuts), water pumps in the railway yards, major river bridges (24 just over the Seine between Paris and Rouen in Normandy), tunnels, telephone and telegraph lines, heavy lifting cranes, 36 airfields, 45 gun batteries, and 41 radar installations that the enemy would desperately need to throw back the invaders.

When the first invasion ships set sail from England on June 4, 1944, and troops finally set foot on Festung Europa, Fortress Europe, two days later, the Allies had neutralized the Luftwaffe over France (the Germans had less than 160 serviceable aircraft), degraded the enemy’s ability to move on land, and breached the “impregnable” Atlantic Wall in a matter of hours to rapidly forge their beachheads for the inevitable liberation of Western Europe.

German Atlantic Wall Defenses on the Eve of Operation Overlord

|

Above: Map of the 1,668-mile/2,684-kilometers-long Atlantic Wall shown in green. Stationed behind the wall were 46 German operational divisions with another 7 divisions in the process of being formed. The wall, which included an estimated 15,000 reinforced-concrete structures, hugged the coastline from Norway to Spain in varying degrees and was most elaborate facing the English Channel, particularly in the Pas-de-Calais (French name of the Dover Strait), which was in sight of the English coast. Touted by Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels to be impenetrable, the wall consisted of an extensive system of coastal fortifications built between 1942 and 1944 as a defense against an anticipated Allied invasion of the continent. In France the wall comprised a string of reinforced concrete casemates housing heavy-caliber guns such as three 406mm naval guns at Battery Lindemann between Calais and Cap Blanc-Nez opposite Dover, bunkers housing smaller artillery (100–210 mm guns), and pillboxes along the beaches or sometimes slightly inland, occasional stationary flamethrowers and searchlights, as well as barbed-wire entanglements, mines, and steel or concrete antitank obstacles (e.g., Czech hedgehogs and pyramid-shaped tetrahedrons) planted on the beaches or in waters just offshore. Admittedly a major engineering feat for its time, the Atlantic Wall, in the opinion of the inestimable Stephen Ambrose, author of D-Day June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II, “must . . . regarded as one of the greatest blunders in military history”; to wit, at Utah Beach the wall held up the invading U.S. 4th Division for less than one hour. At Omaha the wall delayed the 29th and 1st divisions for less than a day. At Gold, Juno, and Sword it held up the British and Canadian invaders for about an hour. “Once it had been penetrated, . . . [the Atlantic Wall] was useless,” Ambrose said.

|  |

Left: In late November 1943 Field Marshal Erwin Rommel took command of the ad hoc German Army Group B in occupied France, reporting directly to Hitler. (Only in mid-January 1944 did Hitler place the Seventh and Fifteenth Armies under Rommel, thus making Heeresgruppe B an operational reality under Oberbefehlshaber West Field Marshal Gert von Rundstedt.) Rommel, in his role as Inspector-General for Northern Europe, was also responsible for Atlantic Wall defenses on the French coast facing England, as well as those from Belgium north to Denmark. Above almost everyone else in the German High Command, Rommel was a genius at waging successful war even against a more numerous and better-equipped foe. To do this Rommel employed his own men, conscripted civilians, brought in slave laborers, and made use of more than a quarter million foreign workers, working hundreds of thousands of men to exhaustion, to make the French coast as impervious as possible to invasion. “We’ll have only one chance to stop the enemy, and that’s while he’s in the water . . . struggling to get ashore,” he preached on hectic inspection tours. In this photo, likely taken on April 18, 1944, when he was accompanied by four war correspondents, Rommel, his officers, and commanders of the positions undergoing inspection can be seen inspecting an installation of 15 to 20 ft/4.6 to 6.1 m wooden obstruction beams (Hemmbalken), 3 to 6 rows deep, on a beach near Calais meant to disrupt an amphibious operation, whether at high or low tide. Some beams were topped with lethal sawtooth devices and artillery shells or Teller (German for “plate”) mines to rip open or detonate when Allied landing craft passed over them. The Allies modified their original plans to land troops at high tide, closer to the shore, in favor of landing at a rising tide when the obstructions and mines could be seen and avoided. The disadvantage with the revised plan was that it increased the length of beach to be crossed.

![]()

Right: In 1943 German troops had begun using hydraulic pressure hoses to assist in planting high wooden poles (Hochpfaehlen) in beach sand as obstacles to landing craft. Pressure hoses knocked installation time from 45 minutes to 3 or 4 minutes compared to using clumsy pile-drivers. In February 1944, on a tour of Channel beaches in Pas-de-Calais (since 2016 part of Hauts-de-France) opposite England, Rommel ordered the technique used to place wooden beams, hedgehogs made out of steel girders, and other anti-landing obstructions along Normandy’s beaches. Out of over 4 million mines laid on Channel beaches between Calais and Cherbourg on the Cotentin Peninsula, nearly 11,000 were installed on the coastline where the Allies would land. Despite the measures taken in fortifying the northern coast of France, Rommel sensed they would not be enough to throw the invaders back into the sea. What’s more, the kind of manpower he needed to do justice to the job so far was simply not there—casualties in other theaters of war.

|  |

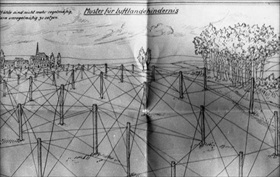

Left: Rommel sent his subordinate commanders sketches like the one depicted here for laying out wooden log and wire defenses against airborne assaults. Barbed wire and tripwires were to be strung between the poles. The complete system of wooden poles and interconnecting wires was called Luftlandehindernis.

![]()

Right: “Rommel’s asparagus” (Rommelspargel) refers specifically to wooden poles used against aerial invasion. Wooden tree trunks and logs set in French fields and meadows in 1944 were intended to cause damage to military gliders (e.g., by tearing off their wings) and to kill or injure glider infantry in an uncontrolled landing. Though more than a million of these fiendish wooden spears were erected, their effect on the invasion of Normandy was inconsequential.

Rare Color Footage: From D-Day to Liberation of Paris, 1944

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click