ALLIES ASSAULT ITALIAN MAINLAND SOUTH OF ROME

Gulf of Salerno, Italy • September 9, 1943

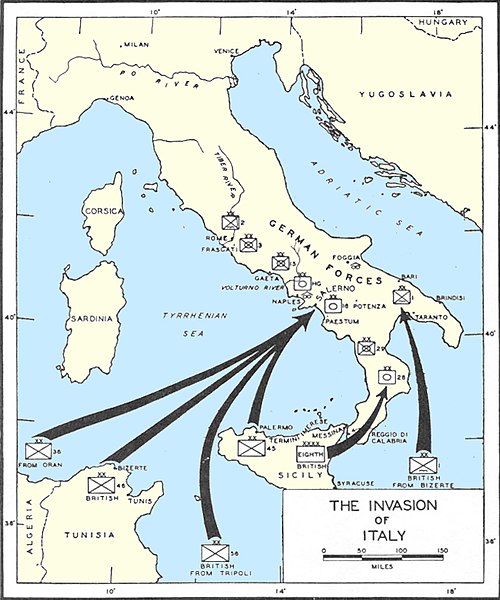

On this date in 1943 in Italy, the Allies from their strongholds in North Africa and Sicily invaded the boot-shaped Italian mainland at the historic port of Salerno 29 miles/47 km southeast of Naples (Operation Avalanche), with diversionary landings at Reggio di Calabria (Operation Baytown, September 3, 1943), which lay on the “toe” of the Italian Peninsula, and Taranto (Operation Slapstick, September 9), the Italian naval port and airfields that lay in the “instep” of the Italian heel (see map). (A landing farther north near the Italian capital, Rome, would have been too far from Allied air support bases in Sicily.) Allied bombing missions during the first week of September softened up the Salerno beaches and plain.

In landing on the Italian mainland U.S. forces were returning to the European continent for the first time since 1918. The day before the Salerno assault, September 8, both Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, and Marshal of Italy Pietro Badoglio, former Chief of Staff of the Italian Army and now Benito Mussolini’s replacement as head of state, publicly announced Fascist Italy’s unconditional surrender, though the 2 sides had negotiated surrender terms 5 days earlier. Immediately, King Victor Emmanuel III and the Italian high command forsook Rome for the safety of Bari on the Adriatic coast, directly north of Taranto.

After Mussolini’s fall from power 6-and-a-half weeks earlier (July 25, 1943), an enraged Adolf Hitler declared the Italians to be the “bitterest enemy.” Dissuaded from attempting a coup against Badoglio’s new government, Hitler directed his armed forces to take over the defense of Italy and occupy Rome, funneling fresh divisions from Austria through the Brenner Pass into Italy since the start of August—this as a resurgent Red Army made gains on Germany’s Eastern Front. Three days later, on September 12, 1943, German commandos snatched Mussolini from Italian captivity high in the Apennine Mountains and soon placed Il Duce (Italian, “the leader”) at the head of a German-imposed puppet government in Northern Italy, the Italian Social Republic (Repubblica Sociale Italiana).

The Allied invasion of the Italian mainland unleashed 20 months of confusing and murderous turmoil in Italy between Axis and Allied armies and Italian Fascists and anti-Fascists. On April 27, 1945, as Allied troops advanced through Northern Italy, Italian partisans captured Mussolini trying to escape to Switzerland, executed him the next day, and hung his bloodied corpse, along with those of his mistress and 4 Fascist leaders, from a girder at an Esso gas station in the Piazzale Loreto in Milan. A total of 15 bodies of leading Fascists were dumped in the city’s square for grizzly display.

Operation Avalanche: The Allied Invasion of Mainland Italy, September 1943

|

Above: Breaching Hitler’s “Fortress Europe” (Festung Europa). Once established on the Italian mainland, the Allies hoped to secure complete naval and aerial domination of the Mediterranean Theater, secure strategic ports and airfields for future operations against Fortress Europe, knock Italy out of the war, entrap Southern Italy’s German defenders behind Allied lines, and force the remaining German forces to retreat north of the Alps. Not everything went according to plan. Instead, the Battle of Salerno became a bloody and vicious struggle to stay ashore or be pushed back into the sea.

|  |

Left: Six-foot 3-inch/189.5 cm Lt. Gen. Mark Clark, Commanding General, U.S. Fifth Army on board USS Ancon, a converted ocean liner, during the landings at Salerno, on Italy’s west coast, September 12, 1943. Clark commanded the first American army to see active duty in Europe. However, his conduct of operations throughout the Italian campaign is controversial, but Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, who had earlier made Clark his deputy commander in chief in the North African Theater, considered him a brilliant staff officer and trainer. (He’s “the best organizer, planner, and trainer that I have met,” Eisenhower said of Clark.) Clark (1896–1984) won many awards during his 36‑year career with the army, including the Distinguished Service Cross, subordinate only to the Medal of Honor, for extreme bravery in war. (The award was recognition of Clark’s assuming direct command of an antitank unit that stopped 18 German tanks at point-blank range during the second major German counterattack at Salerno.) In March 1945, the 48-year-old became a full general, the youngest American ever to wear four stars to this day.

![]()

Right: Artillery being landed during the invasion of mainland Italy at Salerno, September 1943. By sundown on D‑Day, more than 50,000 Allies (out of a total of 189,000 soldiers, sailors, and airmen on September 16) were ashore and had pushed inland as much as 8 miles/13 km. Their intention was to cross the level Salerno plain, cross over the foothills to the mountain passes and through them to Naples, where they could use its excellent port facilities and airfields as a main supply hub and base for future Allied operations in Italy.

|  |

Left: The Allies projected that the Germans might have 39,000 men facing them on D‑Day but on D+3 would have a force of 100,000. Under the command of savvy and experienced Field Marshal Albert Kesselring German units, along with Italian military personnel pressed into service, succeeded in positioning mortars and artillery (like the one shown in this photo) on the high ground in a semicircle covering the whole coastal area. On September 13, “Black Monday,” Clark’s Fifth Army, pinned down to a thin bridgehead, desperately tried clawing its way out of the jaws of defeat. Clark and his staff had already discussed preliminary plans for a seaborne evacuation. Twenty-four hours later the crisis had passed after the nighttime drop on September 13/14 of 2 parachute infantry regiments from the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division, plus another reinforcing PIR drop. Kesselring began withdrawing his hard-fighting forces from Salerno.

![]()

Right: The crescent-shaped, 35‑mile/-56‑km-wide Avalanche landing zone was secured at the cost of 12,500 Allied casualties and MIAs on September 16, 1943. On that date Bernard Law Montgomery’s British Eighth Army, moving up from the south (Monty’s forces had landed unopposed at Reggio di Calabria, just across the Strait of Messina from Sicily’s east coast on September 3; see map), linked up with Clark’s battered Fifth Army. The bridgehead was consolidated on September 18. The next day Allied forces (10 nationalities filled their ranks) pushed northwest towards Naples, which was reached on October 1. In this photo from September 22, 1943, men of the 2/6th Battalion, Queen’s Royal Regiment advance past a burning German Panzer IV tank in the Salerno area. The regiment saw heavy fighting at Salerno, Monte Casino, and Anzio.

Operation Avalanche: British Newsreel of Allied Naval Shelling and Amphibious Landing at Salerno, Italy, September 9, 1943

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click