ALL-BLACK BATTALION RAISES BARRAGE BALLOONS OVER D‑DAY BEACHES

Normandy, Liberated Northwestern France • June 7, 1944

On this date in 1944 soldiers of the U.S. First Army’s 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion succeeded in permanently raising the first of a slew of 35‑ft./11.6‑m‑long hydrogen-filled, low-floating barrage balloons that would bob in the skies over Omaha and Utah invasion beaches. The morning before, hundreds of trained but unseasoned men of the 320th—the only African American combat unit to take part in Operation Overlord’s initial landings on June 6—had exited their landing crafts under withering fire. The men slogged through 56°F/13°C surf lugging the first of 6,600 hydrogen gas cylinders, 50‑lb/23‑kg hand winches, reels of cable, and other supplies. A few men wearing leather gloves manhandled the first several dozen Very Low Altitude (VLA) gasbags onto Normandy’s beaches. Three 320th men were killed and 17 wounded that day.

As an uneasy darkness settled on the first day, balloon crews on Omaha Beach, trying hard not give German artillery observers and snipers something to sight in on, slowly cranked 12 bullet-shaped, steel-cable-tethered “babies,” as they called their 125 lb/57 kg charges, hundreds of feet/many dozens of meters into the air. Made of 2‑ply cotton fabric impregnated by vulcanized or synthetic rubber and coated with aluminum, not a single “baby” survived the morning. On Utah Beach balloon crews deliberately cut loose their 25 floating gasbags on suspicion that they were drawing enemy fire on themselves. (They weren’t.) Not until the evening of D+1 were more lighter-than-air balloons floating over both American invasion beaches, 20 over Omaha and 13 over Utah, and there they stayed. By June 21, 141 silvery orbs dotted the skies.

Nearly 4 years earlier, on September 16, 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Selective Training and Service Act requiring all able-bodied men aged 21 to 35 (later raised to 44) to serve in the U.S. armed forces for at least 12 months. For many military-aged men service turned into years that lasted the duration of the global conflict and beyond. A total of 10 million American citizens and residents were drafted and 6.1 million voluntarily enlisted, among them 1.2 million African American men and women. Yet out of a total of 57,500 U.S. soldiers who landed on 2 invasion beaches in Northwestern France on June 6, 1944, fewer than 2,000 were black. Of these, two-thirds were assigned to non-combat units where, under appalling conditions, they served with honor, distinction, and courage as stevedores, truck drivers, and maintenance men, unloading and transporting crucial supplies from ships and landing craft to the beaches and to points beyond where they were needed.

Unique among the few black servicemen on D‑Day were 621 men who, from their complement of 1,500 black soldiers and 49 officers, comprised the 320th’s initial assault force. Divided into 4 batteries, three-quarters of the men were strewn across 5 miles/8 km of Omaha Beach, one-quarter on Utah. The planned 1‑day landings took 5 days. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander Allied Expeditionary Force, praised the all-black balloon flyers, writing they had “proved an important element of the air defense team.” He continued: “I commend you and the officers and men of your battalion for your fine effort which has merited the praise of all who have observed it.”

The nucleus of D‑Day’s 320th balloon flyers started training in December 1942 in the U.S. Jim Crow South. Sadly, in the early 1940s the U.S. Army was highly segregated. Though black servicemen at the time were chiefly relegated to support roles, by 1944 50,000 out of 700,000 black soldiers would eventually serve as frontline troops, for example, on the ground as tankers in Lt. Gen. George S. Patton Jr’s U.S. Third Army’s all-black 761st Tank Battalion (“Black Panthers”) and in the air as the celebrated Tuskegee Airmen of the 332nd Fighter Group and 99th Fighter Squadron.

Following 140 days on the frontline in France the 320th balloon crews shipped home to train for more action abroad. The men were slated to reprise their barrage balloon role, this time against fleets of 1‑way fliers known by their Japanese name, kamikaze. However, a pair of mushroom clouds and the entry of the Soviet Union into war with Japan in August 1945 brought the curtain down on further combat and with it on the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion’s extraordinary service to their country but, fortunately for us who like to read, not on the memory thereof. Do yourself a favor: read the utterly compelling account of these African American heroes’ service in Linda Hervieux’s 2016 HarperCollins publication, Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day’s Black Heroes, at Home and at War.

320th Barrage Balloon Battalion: D-Day’s Black Heroes

|  |

Left: The men of Headquarters Company and Battery A of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion (sometimes referred to as the 320th VLA Battalion) began landing on Omaha Beach at 9 a.m., a little more than 2 hours into the June 6, 1944, Allied invasion of Northwestern France. Battery C began splashing onto adjacent Utah Beach on the same day. After darkness had set in an hour-and-a half earlier, Battery A floated a dozen barrage balloons over Omaha Beach. Within hours of first light, enemy fire had downed all of Omaha’s balloons. Later that second invasion day Battery B landed at Omaha with new barrage balloons, which were quickly filled with hydrogen gas and floated. By their very nature barrage balloons are passive forms of defense, one that force enemy pilots to fly above them while making surface targets harder to hit. Many vessels crossing the English Channel also flew barrage balloons, more to boost shipboard morale than deter low-level enemy attacks en route to Northwestern France or while beached at the shoreline as LSTs (“large stationary targets,” their nickname). This photo of Omaha Beach taken a few days after the initial landings shows barrage balloons flying over ships and landing craft disgorging fresh stocks of men, material, and munitions needed for expanding the Normandy beachhead. Just 7 days after D‑Day more than 300,000 Allied troops had landed in France, and the invasion beaches were fully under their control. By that time, in addition to troops, 50,000 vehicles and over 100,000 tons of equipment had been deposited on Normandy’s beaches.

![]()

Right: In this rare daytime close-up of members of 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion in action Battery A Cpl. A. Johnson of Houston, Texas, with help from 2 men in his 3‑man crew, walks an inflated 125 lb/57 kg, 35‑ft./11.6‑m‑long VLA balloon toward a 50 lb/23 kg hand winch that will float the balloon over Omaha Beach. Most balloons were raised at night after Allied planes had returned to their bases. Filled with hydrogen or noncombustible helium gas, they could be raised in a minute. Costing $600 apiece ($10,952 in 2025 dollars), VLAs flew at very low altitudes (between 200 ft./61 m and 2,000 ft./610 m), and they were planted at irregular intervals, making enemy efforts to pilot a strafing or bombing run through the hazardous, nearly invisible thicket of dangling 1/8 in./0.3 cm steel cables extremely difficult. The cables could neatly slice off a warplane’s wing or tail or foul a propeller. Some cables were made more lethal when 4 lb/1.8 kg bomblets were attached to them, turning them into “flying mines.” On D+10 the 320th battalion scored a confirmed “kill” by cutting off the wing of a 2‑engine Luftwaffe Junkers Ju 88 flying over Omaha Beach. The battalion was also credited with a large number of possible “kills.” A newspaper reporter on Omaha Beach marveled that one of the Allies’ more unusual lines of defense was “one of the most important missions of the war.” Sadly, the role played by the 320th did not make it into two of the most popular and highest-grossing cinematic retellings of the Normandy landings, Darryl F. Zanuck’s The Longest Day (1962) and Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan (1999).

|  |

Left: The Jim Crow South was home to most of the U.S. Army’ training camps. White officers were put in charge of black units. This was true of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion, a white South Carolinian, Lt. Col. Leon J. Reed, commanding. The all-black balloon fliers were not the first black recruits trained at Camp Tyson near Paris, Tennessee, shown here in this photo. Of the more than 30 balloon units trained at Camp Tyson beginning in March 1942, just 4 were African American. And of those 4 only one, the 320th, was chosen (nobody knows why) for combat. That surprise choice came 11 months after a white American barrage balloon team had made a test appearance on July 11, 1943, during Operation Husky, the invasion of Benito Mussolini’s Italy.

![]()

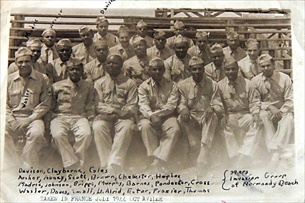

Right: Twenty-three members of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion pose for a photograph at Camp Tyson. The camp, in service from 1941 to 1944, was the training center for the U.S. Coast Artillery Corps and other commands. It consisted of 450 buildings sprawled over 2,000 (eventually 6,000) acres/809 hectares. The camp trained servicemen to fly, build, and repair VLA barrage balloons and equipment. By the end of the war, Camp Tyson’s occupancy ranged from 20,000 to 25,000 soldiers. Interestingly, nearly 600 of over a thousand Luftwaffe aircraft lost in Normandy during the first week of combat were lost not over the invasion coast—the barrage balloons, wrote one newspaperman “keep the front door to the front lines open”—but lost at sea as Germans targeted Allied shipping while thousands of U.S. and RAF fighter planes in turn targeted the attackers. Shipboard and land-based antiaircraft crews positioned near the black balloonists upped the ante on German raiders becoming MIAs (missing in action).

African American Fighting Units in World War II

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click