AFTER SURRENDER GREEKS STARE HOLOCAUST IN FACE

German 12th Army HQ, Larissa, Greece • April 21, 1941

After their prime minister’s suicide 3 days earlier representatives of the leaderless Greek government signed a document of capitulation at the headquarters of the German 12th Army at Larissa in Central Greece on this date in 1941. Fourteen Greek divisions laid down their arms. An armistice that included Italy was concluded on April 23, 1941. Four days later soldiers of the Wehrmacht (German Armed Forces) raised their swastika war banner (Reichkriegsflagge) over the Acropolis, the ancient Greek monumental complex overlooking Athens, the Greek capital. At month’s end, April 30, the Wehrmacht juggernaut reached Greece’s southern shore and captured 7,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers out of the roughly 58,000 dispatched by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill at the top of the month. Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and their ally Bulgaria divided their Hellenic spoils among themselves (see map below).

With a collaborationist Greek government sitting in Athens, the Germans were able to implant their anti-Semitic doctrines on foreign soil. When Operation Marita, the joint German-Italian attack on Greece, kicked off on April 6, 1941, an estimated 74,000–86,000 Jews and their ancestors had been living in Greece since the 4th century BCE. In 1940 Jews represented roughly 1.1 percent of the Greek population of 7,344,860. Around 50 CE Paul the Apostle and 3 companions preached to the Jewish communities in Macedonia, Northeastern Greece. The oldest and the most characteristic Jewish group that has inhabited Greece are Greek-speaking Romaniotes, also known as “Greek Jews,” who hail from present-day Romania. A smaller group, the 53,000-strong (1943 estimate) Sephardic Jewish community of Thessaloniki (aka Salonica,) in Macedonia originated when they fled Spain, Portugal, and Italy during the late Middle Ages.

Gradually German and Bulgarian military authorities imposed a series of decrees limiting Jewish participation in public life in their zones of occupation. (Until September 1943 the Italian occupation zone was hardly affected by German and Bulgarian anti-Semitic ordinances and deportations to work and death camps.) In the second half of 1941, the first deportations to the camps came about when the Bulgarians agreed to German requests to be allowed to round up all Jews then living in Macedonia, who made up more than half of Thessaloniki’s population until the early 1900s, and in neighboring Thrace in Northeastern Greece. Despite efforts by Greeks to protect their wartime Jewish population, some 4,000 Jews were deported from Thrace in the Bulgarian occupation zone to the Treblinka extermination camp 50 miles/80 kilometers northeast of Warsaw, Poland. On July 11, 1942, the Germans rounded up the Jews of Thessaloniki in preparation for forced labor assignments (Arbeitseinsaetze). The community paid a ransom of 2 billion drachmas (a period of catastrophic hyperinflation and famine) for their short-lived freedom. Of the 55,000 Thessaloniki Jews the Germans deported to work and extermination camps in 1943 in Poland, mainly to Auschwitz, fewer than 5,000 survived by hiding or joining Greek resistance groups.

Beside Thessaloniki’s, losses were significant in places like Ioannina in Northwestern Greece, Corfu, an island off Northwestern Greece, and the island of Rhodes in the Southeastern Aegean Sea, where most of the Jewish population was deported and killed. In contrast, larger percentages of Jews were able to survive where local residents such as Athenians and citizens in Larissa in North Central Greece and Volos, a city and port in Eastern Greece, hid the persecuted Jews. Perhaps the most important rescue efforts took place in the Greek capital, where some 1,200 Jews were given false identity cards following the efforts of Athens’ archbishop and police chief. Sadly, by 1945, after the German and Bulgarian occupiers had been expelled from the country, between 82 and 92 percent of Greek Jews had been murdered, one of the highest proportions of Jewish deaths in Europe.

Greek Holocaust, 1941–1944

|

Above: The Axis occupation of Greece was divided between Germany, Italy, and Bulgaria. German forces occupied the most strategically important areas—namely Athens and its harbor Piraeus, Thessaloniki, Central Macedonia, and several Aegean Islands lying west and south of mainland Greece, including most of Crete. East Macedonia and Thrace came under Bulgarian occupation and were annexed to Bulgaria, which had long claimed these territories. The remaining two-thirds of Greece were occupied by Italy, with the Ionian Islands west of the mainland directly administered as Italian territories. Following the dismissal and arrest of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini on July 24–25, 1943, and Italy’s capitulation to the Western Allies on September 3, 1943, Greece’s Italian zone was taken over by Germans at gunpoint. During the triple occupation the Jewish population of Greece was nearly eradicated. Of its prewar population of 75,000–77,000, around 11,000–12,000 survived, often by joining the Greek resistance or being hidden by locals.

|  |

Left: After Greece, Germany, and Italy concluded an armistice on April 23, 1941, the citizens of Athens braced for the arrival of the Axis victors by staying indoors, their windows shut. On the night of April 26, Athens Radio urged their listeners: “Brothers! Have courage and patience. Be stout hearted. We will overcome these hardships.” German and Italian troops marched into Athens on April 27, the Germans driving straight to the Acropolis to hoist their battle flag. Nearly 3½ years later, on October 12, 1944, the Germans abandoned the Greek capital and by the end of the month they had been chased from mainland Greece. British troops returned on October 14 and 4 days later the Greek government-in-exile returned as well. Based on 1939 census figures between 7 and just over 11 percent of Greece’s 7.2 million inhabitants had died during the Axis occupation and the events leading up to it: 171,188 civilian deaths due to military activity and crimes against humanity, 300,000–600,000 civilian deaths due to war-related famine and disease, and 35,100 military deaths from all causes.

![]()

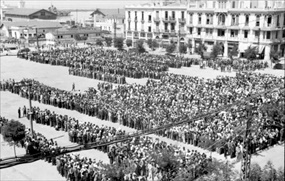

Right: On July 11, 1942, the German chief civilian administrator imposed forced labor on Thessaloniki’s Jewish population. Jews between the ages of 18 and 45 reported to Eleftherias (Liberty) Square that sabbath morning as shown in this photo. In extreme heat 9,000 fully clothed men were forced to perform calisthenics for 6½ hours. Some 2,000 unfortunates were snared as forced laborers for the German Army. “Black Sabbath” is remembered as the beginning of the destruction of the 56,000-strong Jewish community of Thessaloniki. The next February Thessaloniki’s Jews were confined to 2 ghetto-like areas of the city. In March 1943 German and Bulgarian officials began mass deportations, sending the Jews of Thessaloniki and Thrace in packed boxcars to distant Auschwitz and Treblinka in Poland. By the summer of 1943, Jews in German and Bulgarian zones were practically gone; only Jews in the Italian zone remained up to September 1943. Ninety-one percent of Thessaloniki’s Jews perished during the Greek Holocaust. In the Bulgarian zone, death rates surpassed 90 percent.

|  |

Left: At the beginning of World War II the Jewish community of Ioannina in Northwest Greece numbered about 5,000. Their presence in Ioannina was an ancient one, going back perhaps to the 4th century BCE. They were Romaniote Jews, Greek-speaking Jews who had absorbed Hellenistic culture and now comprised some 15 percent of Ioannina’s inhabitants. Most of the Jews of Ioannina were traveling merchants, laborers, and shop keepers. As of April 1941 the city found itself in the Italian zone of occupation. With Mussolini’s sacking in September 1943, Ioannina came under German control. The days of the community were numbered. The fateful number came due the next year, on March 25, Greek Independence Day. Only given time to gather up a few possessions, the Jewish community was herded onto trucks, taken to Larissa, kept for over a week, then placed in cattle cars and sent to the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center. Their journey ended on April 11, 1944. Most were ushered to the gas chambers on arrival. After the Holocaust barely 160 Ioannina Jews found their way home.

![]()

Right: Not all atrocities and crimes against humanity in Greece that were committed by Germans or, to a lesser extent, by Bulgarians and Italians were directed at Jewish civilians. A particularly egregious example by German soldiers directed at blameless Greek villagers was the Distomo massacre. This massacre of Greek innocents—one of more than 90 during World War II—is also part of the Greek Holocaust. The Wehrmacht had standing orders to use terror to frighten Greeks into not supporting the andartes (Greek partisans). On June 10, 1944, an andarte band ambushed a Waffen-SS convoy near the small village of Distomo in Central Greece. Hundreds of revenge-seeking Germans retaliated with demonic ferocity, shooting people and animals as they later advanced on the village. Once in Distomo they raped all females, mutilated their wombs and severed their breasts, cut the throats of infants, shot or hanged all boys and men, and used bayonets to crucify men on trees lining the roads. The German clean-up operation, or Sauberungsunternehmen, bagged 228 civilian dead. A Swedish Red Cross worker driving a truckload of food and medicines to Distomo on June 14, 1944, entered the village, parts still engulfed in flames, empty of life, looted of household goods, utterly destroyed.

The Axis Occupation of Greece, April 1941 to October 1944

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click