ADM. YAMAMOTO TO VISIT BOUGAINVILLE GARRISON

Rabaul, New Britain Island, Papua New Guinea • April 13, 1943

On this date in 1943 the headquarters of Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto on Rabaul, the important Japanese garrison on New Britain Island in the Bismarck Archipelago, sent a coded military radio signal to various Japanese commands in the Western South Pacific. The message listed the dates and schedule of the admiral’s upcoming inspection tour of the Solomon Islands and New Guinea as well as the number of transport planes and fighter escorts in his party. The widely revered Yamamoto was the commander in chief of the Combined Fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy and the planner of the December 7, 1941, surprise attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet anchored in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. By spring 1943, however, the fortunes of Japanese armed forces in the Western South Pacific were sinking. U.S. Marines and Army soldiers had recently captured the island of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands chain after a 6‑month campaign (August 1942 to February 1943) despite the terrible sacrifice of 38 Japanese ships, 638 aircraft, and 19,200 dead. Stung by criticism that senior commanders were not visiting the front to ascertain the situation and turn things around, Yamamoto resolved to pay the first of his visits to naval air units on Bougainville, the largest island in the Northern Solomons (see map below).

The Yamamoto radio message was sent in the new JN-25D naval code variant, but that didn’t stop American cryptanalysts from deciphering it in less than a day. Adm. Chester Nimitz, the U.S. commander in the Pacific, authorized the operation to shoot down Yamamotos’s airplane; he considered killing an enemy officer, even the highest-ranking officer in the Imperial Japanese Navy, purely a military matter. (There is no official record of U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorizing the Navy Department to kill Yamamoto.) The fiery U.S. Pacific Fleet commander William “Bull” Halsey issued his own communiqué to convey to the designated assassins: “TALLY HO X LET’S GET THE BASTARD.”

The end came for Yamamoto exactly a year after the famous Doolittle Raid on Tokyo. On April 8, 1943, a flight of 16 Army Air Forces long-range, twin-engine, twin-boom Lockheed P‑38 Lightning fighters from Kukum Field on Guadalcanal ambushed Yamamoto’s green-striped Mitsubishi G4M Betty medium bomber as it, along with its fighter cover and a second Betty, approached Balalae Airfield on Shortland Island just south of Bougainville. The airmen had managed to do this without the aid of radar, instead intercepting their prey by calculating the speed of the Betty bomber transports (there were two), probable wind speed, the enemy’s probable flight path, and Yamamoto’s reputation for arriving on the dot. One Betty bomber trailing heavy black smoke crashed in Bougainville’s dense jungle, the other crash-landed in the ocean, where 3 people survived. The next day a Japanese search-and-rescue party hacked its way to the jungle crash site and Yamamoto’s body, belted upright in his seat and still holding his jeweled samurai sword. The admiral had received 2 0.50-caliber bullet wounds, one in the back of his neck. His staff cremated his remains and forwarded the ashes to Tokyo aboard his last flagship, the super battleship Musashi.

On June 5, 1943, Yamamoto was given a full state funeral. Amid the million mourners Showa Emperor Hirohito promoted the fallen admiral to Marshal Admiral (admiral of the fleet) and awarded him the Order of the Chrysanthemum (1st Class). The German government, Japan’s Axis ally, posthumously awarded Yamamoto the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords, the only foreign recipient to receive that honor. Conversely, Americans greeted Yamamoto’s death, when it was publicly announced on May 21, 1943, as sweet payback for his role in initiating the war between America and Japan. The U.S. Navy awarded the Navy Cross to pilots of the “killer flight.”

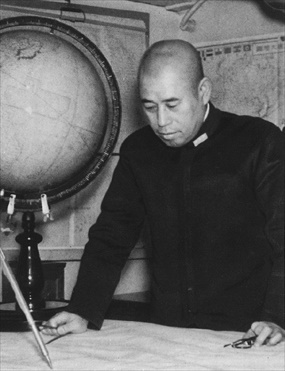

Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto (1884–1943): Japan’s Naval War Leader

|

Above: This map shows the route of Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto’s planned 2‑hour flight on April 18, 1943, from the major Japanese base at Rabaul on New Britain to a Japanese naval base on the small island of Balalae near Bougainville. The U.S. Army Air Forces’ daring top-secret kill mission, Operation Vengeance, succeeded in shooting down both of Yamamoto’s transport bomber aircraft as he and his party were en route to visit naval air bases in the Solomom Islands and New Guinea. The death of the “Architect of the Pacific War” raised the morale of Allied forces and the American people and damaged the morale of the Japanese (“an insupportable blow”), especially those serving in the Imperial Japanese Navy.

|  |

Left: In 1939 Yamamoto was promoted to admiral and sent to sea as commander in chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet. He is shown here aboard his flagship, the battleship Nagato in 1940. Yamamoto had vigorously warned against war with the United States, where he had served his country as a naval attaché in Washington from January 1926 to March 1928. Yet, patriot to the core, when he was ordered to fight, he waged war with a vengeance beginning with an attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, that he and his staff had been planning since early 1940. In the first half of 1942 powerful Japanese naval formations supported thrusts against poorly defended American, British, Australian, and Dutch interests in the Pacific. The naval Battles of the Coral Sea (May 4–8, 1942) and Midway (June 4–7, 1942) ended 6 months of Japanese ascendancy. The U.S. campaign on Guadalcanal (August 1942 to February 1943) forced Japan into a war of attrition, and Yamamoto sensed this before his death on April 18, 1943. The island-hopping campaign by the U.S. and its allies that began with invading Guadalcanal took Allied forces to the shores of Japan itself.

![]()

Right: Yamamoto saluting aviators just before enplaning on his ill-fated flight to Bougainville, where he had planned face time with officers, the sick and wounded and saluting his warriors. Yamamoto had given himself a year to deprive the U.S. of the naval capacity to oppose Japanese expansion in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. But time had definitely run out for him and his emperor after American cryptanalysts had broken Japanese naval codes and used the decrypts to penetrate IJN’s plans and those of Yamamoto’s April 18 visit. After the 4 pilots assigned to the “killer flight” had dispatched Yamamoto’s transport bomber to a jungle grave and the other bomber to a watery grave, the leader of the 339th Fighter Group that flew the avenging P‑38 Lightnings radioed Guadalcanal that the “son of a bitch” would never again threaten America.

Contemporary U.S. and Japanese News Footage of the Shoot-Down of Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, April 18, 1943

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click