“BRACE YOURSELVES” CHURCHILL TELLS BRITISH

London, England • June 18, 1940

Four days after the fall of Paris to German invaders, Charles de Gaulle, a tall (66 ft., 5 in./196 mm), young (49), relatively unknown French brigadier general who had escaped to England on June 17, 1940, addressed the French people in a radio broadcast from the BBC in London on this date in 1940. In a celebrated call to arms (“Appel du 18 juin”), de Gaulle said (in French): “The flame of French resistance must not go out; it shall not go out.” He appealed to French soldiers, engineers, and specialized workers from the armaments industry to join him in London to continue the fight. Interestingly, former Deputy Premier Maréchal Philippe Pétain, who had just assumed authority over a defeated France, used the term “resistance” the day before in a radio address to the French people, ending it with the words: “It is with deep sorrow that I tell you today that the fight must end.”

The English language service of the BBC gave de Gaulle’s “Free French” movement a 5‑minute slot each evening—it helped that the time slot was during curfew hours, when Frenchmen were required to stay indoors. Over the next 10 days de Gaulle’s voice gained authority. His message was the same: It was a crime for 38 million French men and women in occupied France to submit to their occupiers, and it was an honor to defy them. “Honor, common sense, patriotism demand that all free Frenchmen continue the struggle wherever they are and however they might,” de Gaulle said in his June 22 broadcast, which was a repeat of his June 18 call to arms, this time to a larger and more responsive audience. “Since they whose duty it was to wield the sword of France have let it fall,” he said accusingly several weeks later of the top military and political people who coalesced around the venerable 84‑year-old Marshal of France, “I have taken up the broken blade.”

Also on this date, June 18, 1940, Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov congratulated Adolf Hitler for the “splendid successes of the German Wehrmacht” (armed forces) in France and the Low Countries. Molotov would live to regret his flattering words just over a year later, when Hitler violated the Molotov-Ribbentrop Nonaggression Pact of August 1939 by launching his surprise invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa).

As British citizens anxiously awaited for the next shoe to drop—namely, Germany’s inevitable invasion attempt of their island nation—Prime Minister Winston Churchill, barely 6 weeks in office, stood before the House of Commons in London and in front of BBC microphones to say: “The Battle of France is over. I expect that the Battle of Britain is about to begin. . . . The whole fury and might of the enemy must very soon be turned upon us. Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this island or lose the war.” Churchill did not flinch from acknowledging the great apparent danger these events posed to Britain’s national survival and national interests in this, the third of 3 speeches he gave during (roughly) the Battle of France (May 10 to June 22, 1940). But he turned the grave situation into a roar of determination and defiance when he concluded his address, saying: “Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, ‘This was their finest hour’.”

Call to Arms: Gen. Charles de Gaulle and Prime Minister Winston Churchill, June 18, 1940

|  |

Left: Gen. Charles de Gaulle in the studios of the BBC in London, October 10, 1941. This photograph has sometimes been used in connection with de Gaulle’s “Appel du 18 juin” speech of 1940, of which no photograph exists. De Gaulle’s June 18th “call to arms” appeal had little immediate military or political impact, for hardly a single Frenchman heard his initial broadcast from his London sanctuary much less ever heard of his name. De Gaulle’s June 18th speech was not recorded, so 4 days later he asked if he could read it again over the air, this time, he wagered, to a larger, more attentive audience. (An audience made all the more attentive because the date of the second broadcast, June 22, was the date representatives of the new Pétain administration formally signed a humiliating ceasefire, the Franco-German Armistice of Compiègne, which divided the vanquished nation into a larger German-occupied zone with Paris as its headquarters and a smaller southern, unoccupied, nominally independent zone with its administrative capital at Vichy where Pétain held sway.) The defiant 49‑year-old brigadier general, who briefly served as undersecretary for war in French Premier Paul Reynaud’s government before it collapsed on June 16, was one of the few military or political leaders in France in the summer of 1940 to flee abroad and from there organize opposition to the German occupation. By early 1941 many patriotic Frenchmen had adopted the upstart general and his two-barred Cross of Lorraine as symbols of French resistance against the Germans and their Pétainist lackeys.

![]()

Right: Winston Churchill giving his famous V-sign (used to represent the letter “V” in “Victory”; Victoire” in French) on May 20, 1940, just 10 days after he became prime minister, and on the day German troops reached the English Channel in preparation for their exterminating the British Expeditionary Force trapped at Dunkirk on the French coast.

![]()

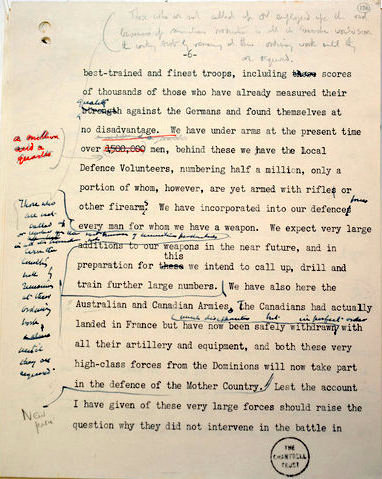

Below: A draft of Churchill’s “Finest Hour” speech shows the way he extensively edited it before delivering it to the House of Commons on June 18, 1940, the start date for German bombing raids on British cities and towns that became an almost nightly occurrence. In 36 minutes of soaring oratory, Churchill sought to rally his countrymen with what has gone down in history as his “finest hour” speech. The speech—ending with the words, “Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, ‘This was their finest hour’”—has resonated ever since. On both sides of the Atlantic and beyond, it has been hailed as the moment when Britain found the resolve to fight on after the fall of France and, ultimately, in alliance with Allied military forces (what would be called the United Nations) to vanquish Hitler’s armies that had overrun most of Europe.

Excerpt from Winston Churchill’s “Finest Hour” Speech to the House of Commons, June 18, 1940

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click