2ND LIEUTANANT KILLS/WOUNDS 50 ENEMY

Near Holtzwihr, Colmar Area, Northeastern France · January 26, 1945

On this date in 1945 U.S. Army Second Lt. Audie Murphy, age 20, commanded an infantry company when it came under attack from two hundred German infantrymen and a half dozen tanks on the outskirts of Holtzwihr, near Colmar in northeastern France. Armed with an M1 carbine, Murphy called in artillery fire. When the tanks and infantry continued to approach, Murphy, who had initially been rejected by both the U.S. Marine Corps and U.S. Army because he was too short (5 ft, 6 in), scampered aboard a burning American tank destroyer and fired a .50 caliber machine gun against an enemy advancing on three sides, turning it back. Wounded in the leg, he held the enemy off for three hours. With his ammunition exhausted, he returned to his company and led a counterattack, forcing the Germans to retreat. For his extraordinary courage, Murphy received the Medal of Honor, the highest military award for bravery that can be given to any person in the United States. During his three years of active service in nine major campaigns across the European Theater (North Africa, Sicily, Italy, France, and Germany), Murphy was credited by the U.S. Army with killing over 240 enemy soldiers while wounding more than 500 and capturing about 100. He became the most decorated soldier in U.S. history. Among his 33 medals, ribbons, citations, and badges were one Belgian and five French medals, including the French Legion of Honor and the French Croix de Guerre. When he left active service with the rank of first lieutenant, Murphy was still under 21. His 1949 autobiographical account of his service, To Hell and Back, was a best seller. With Hollywood good looks, Murphy went on to a long film career (44 films), which included playing himself in a film biography released by Universal-International in 1955 with the same title as the book. The movie version held the record as Universal’s highest-grossing picture until 1975, when the movie Jaws surpassed it. Murphy died three weeks short of his 46th birthday in a plane crash on the side of a mountain near Roanoke, Virginia, on May 28, 1971. Fittingly, his body was recovered two days later on Memorial Day. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery outside Washington, D.C. Notwithstanding his tragic and untimely death, Murphy may very well be remembered as the last genuine American Hero.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0805070869,148253326X,0786445084,0953867706,1468104497,0944019226,0312976550,0700612262,1933337192,0944019382″ /]

Audie Murphy: To Hell and Back

|  |

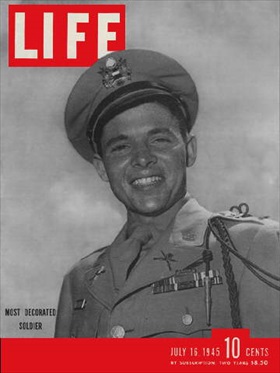

Above: Son of a Texas sharecropper, Murphy (1925–1971) enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1942. He was the recipient of 33 medals, ribbons, citations, and badges, more than had any other soldier in his country’s history, many of them more than once, and most of them awarded before he had turned 21. Medals included the Medal of Honor, Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star, Bronze Star, Purple Heart, Legion of Merit, Combat Infantryman Badge, French Legion of Honor, French Croix de Guerre, and Belgian Croix de Guerre. He appeared next to the caption “Most Decorated Soldier” on the cover of Life Magazine for July 16, 1945.

|  |

Left: On June 2, 1945, near Salzburg, Austria, U.S. Seventh Army commander Lt. Gen. Alexander Patch presented Murphy with the Medal of Honor and the Legion of Merit for his actions at Holtzwihr, France, nearly six months earlier. The official U.S. Army citation for Murphy’s Medal of Honor read in part: “His [Murphy’s] directing of artillery fire wiped out many of the enemy; he killed or wounded about 50. 2d Lt. Murphy’s indomitable courage and his refusal to give an inch of ground saved his company from possible encirclement and destruction, and enabled it to hold the woods which had been the enemy’s objective.”

![]()

Right: A photo taken by a Red Cross worker shows the 19‑year‑old Texan standing in the foreground as Lt. Gen. Patch reads the U.S. Army citation from the makeshift platform on June 2. Years after the war Murphy was asked by a reporter how the Army could have arrived at the casualty figures he supposedly inflicted on the enemy. “I don’t know how they know,” he replied. “Maybe the War Department kept count somehow. Maybe the officers sent in totals. I didn’t keep count. I don’t know how many. I don’t want to know.” In a subsequent interview when asked the question, “How does it feel to have killed 240 men?” Murphy retorted: “To begin with, I didn’t kill that many; how the hell does anyone think it felt. It didn’t feel either way; good or bad. Feeling wasn’t a luxury in the infantry.”

|  |

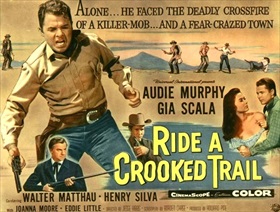

Above: Murphy rose from the rank of private to become a company commander in 30 months of combat duty with the veteran Third Infantry Division. After the war Murphy went on to a successful career as a film star, appearing in 44 feature films and 29 television episodes in 21 years, most of them Westerns. But the war years haunted him all his short life. In a 1955 interview at the time of the release of his autobiographical film To Hell and Back, in which he played himself, Murphy remarked: “War is like a giant pack rat. It takes something from you and leaves something behind in its stead. It burned me out in some ways so that now I feel like an old man. . . . It made me grow up too fast. You live so much on nervous excitement that when it is over, you fall apart. That’s what war took from me, the excitement of living.” Asked in an interview near the end of his life, “How does a soldier get over a war,” Murphy lowered his head and in a barely audible voice said, “I don’t think they ever do.”

Army Hour Interviews Audie Murphy on His Service During World War II

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click