U.S. ATOMIC BOMB PROJECT TAKES OFF

Chicago, Illinois • December 2, 1942

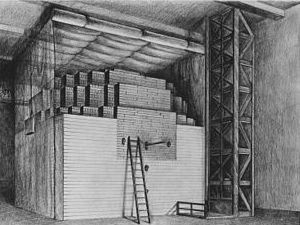

In November 1942 the world’s first artificial nuclear reactor was assembled piecemeal below the bleachers of an unused and unheated double racquetball (squash) court at the University of Chicago’s Amos Alonzo Stagg Field. The impetus for building an American nuclear reactor, which consisted (mostly) of a huge pile of slippery black graphite bricks, was the fear that scientists in Nazi Germany had a 2‑year head start in building a nuclear reactor for their country’s atomic weapons program. Metallurgical technicians from the Chicago university spent 17 days of around-the-clock labor arranging 45,000 bricks weighing 771,000 lb./349,720 kg into an elliptical, some said egg-shaped, pile 2 stories tall, 25 ft./7.62 m wide through the middle, and 6 ft./1.8 m wide at the ends. The pile was named Chicago Pile‑1 (CP‑1). CP‑1’s outermost bricks were solid hunks of graphite, a crystalline form of the nonmetallic chemical element carbon. Most bricks toward the center had holes drilled into them into which 5 lb./2.26 kg slugs of unenriched natural uranium had been inserted—18,000 slugs capable of firing off neutrons every which way. (Discovered in 1932, a neutron, in the parlance of the day, was seen as an “elementary particle” of all atoms except those of hydrogen.) A third component of the pile was cadmium formed into sheets wrapped around wooden rods inserted into the pile. Cadmium served as a kind of neutron sponge that was in place to prevent the pile from prematurely going critical, meaning creating as many new neutrons as are lost.

Assembling Chicago Pile-1 was supervised by its designer, the brilliant Italian-born physicist and 1938 Nobel Prize laureate Enrico Fermi. Fermi (1901–1954) had hit upon using graphite bricks as a neutron “moderator” in CP‑1. Moderating, or reducing, the speed of neutrons when they entered the surrounding graphite would allow a nuclear chain reaction to be sustained when another slug of uranium absorbed the neutrons a fraction of a second later. If the chain reaction—the process by which the nuclei of atoms undergo fission (split) and interact—was not controlled (not moderated), then the result would be the release of a huge amount of kinetic energy in the form of heat—in other words, a nuclear meltdown.

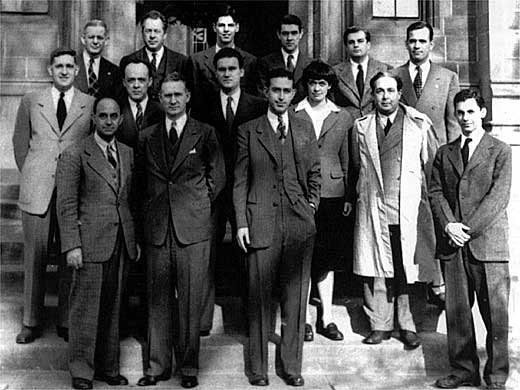

On this date, December 2, 1942, nuclear fission theory and nuclear fission technology came together for Fermi’s team and invited guests—47 men and 1 woman—perched on a high balcony overlooking CP‑1. Inch by inch/centimeter by centimeter Fermi ordered the cadmium-coated control rod (vernier rod), which kept the neutron chain reaction in check, removed from CP‑1 until the pile went critical. Fermi repeated the process several more times during the day. At 3:53 p.m. Fermi achieved the first man-made, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction that released a controlled flow of energy from the atomic nucleus. After 28 minutes Fermi ordered the vernier rod reinserted into CP‑1 and the world’s first nuclear reactor cooled down. That afternoon the birth of the nuclear age was celebrated as a bottle of Chianti made the rounds of outstretched paper cups.

Fermi’s successful demonstration of controlling a nuclear chain reaction shifted the U.S.-led Manhattan Project into overdrive. With a working nuclear reactor in front of them, the men and women of the Manhattan Atomic Bomb Project—they would eventually number 600,000—could double down on building the industrial facilities required to enrich uranium and plutonium (another chemical element) to make them highly fissionable, that is, easily converted into energy when bombarded by neutrons in a nuclear reactor. Facilities were set up in remote U.S. locations in New Mexico, Tennessee, and Washington state, as well as in Canada, for researching the best ways to weaponize nuclear energy and then following that up with related atomic tests. “Little Boy” and “Fat Man,” the uranium-based bomb dropped on Hiroshima and the plutonium-based bomb dropped on Nagasaki, respectively, were just over 2 years away from being put to use to end the war with Japan and finally bring World War II to a close.

Enrico Fermi Demonstrates First Self-Sustaining Nuclear Chain Reaction, Chicago, Illinois, December 2, 1942

|  |

Left: Erected in November 1942 at the University of Chicago, Chicago Pile‑1, as shown in this sketch, was the first successful U.S. nuclear reactor. In the 1930s Fermi and Hungarian-born physicist and inventor Leó Szilárd collaborated on a design of a device to achieve a self-sustaining nuclear reaction—a nuclear reactor. CP‑1 was one of at least 29 experimental nuclear reactors that were constructed in 1942 at Stagg Field. On December 2, 1942, a group of scientists used CP‑1 to achieve the first self-sustaining chain reaction and thereby initiated the controlled release of nuclear energy. CP‑1 contained 45,000 ultra-pure graphite bricks weighing 771,000 lb./349,720 kg that acted as a “neutron moderator” whose purpose was to slow the speed of neutrons, thus allowing a nuclear chain reaction to be sustained. The reactor was fueled by 12,400 lb./5,625 kg of uranium metal and 80,590 lb./36,555 kg of uranium oxide in 18,000 slugs weighing 5 lb./2.26 kg each. Unlike most subsequent nuclear reactors, CP‑1 had no radiation shielding or cooling system as it operated at very low power—about one‑half watt.

![]()

Right: On December 2, 1946, the fourth anniversary of their groundbreaking success, members of the CP‑1 team gathered at the University of Chicago to pose for this photograph. Team leader Enrico Fermi is in the front row on the left. Fermi is often hailed as the “architect of the nuclear age” and the “architect of the atomic bomb.” His peers called him “the Pope.” In the second row on the right in a light-colored trench coat is Leó Szilárd. It was Szilárd (1898–1964) who conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, patented the idea of a nuclear fission reactor in 1934, and wrote the August 2, 1939, letter for Albert Einstein’s signature that prompted President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945) to launch the nearly $2 billion (over $36 billion in today’s dollars adjusted for inflation) Manhattan Project that built the 3 atomic bombs that were detonated during World War II: “Gadget” at the Trinity test site in the New Mexico desert on July 16, 1945, and the 2 atomic bombs that, several weeks later, laid waste to the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, respectively.

Enrico Fermi: Godfather of the Atomic Bomb

![]()

World War II was the single most devastating and horrific event in the history of the world, causing the death of some 70 million people, reshaping the political map of the twentieth century and ushering in a new era of world history. Every day The Daily Chronicles brings you a new story from the annals of World War II with a vision to preserve the memory of those who suffered in the greatest military conflict the world has ever seen.

World War II was the single most devastating and horrific event in the history of the world, causing the death of some 70 million people, reshaping the political map of the twentieth century and ushering in a new era of world history. Every day The Daily Chronicles brings you a new story from the annals of World War II with a vision to preserve the memory of those who suffered in the greatest military conflict the world has ever seen. History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click