JAPANESE PUT MANILA IN CROSSHAIRS

Manila, Philippines • December 10, 1941

At 3:40 a.m. on December 8, 1941 (Manila time), 1 hour and 40 minutes after the start of Japan’s unprovoked air and naval attack on U.S. military installations at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, 62‑year-old Lt. Gen. Douglas MacArthur awoke to a terrible day of his own. Within 3 hours MacArthur learned that Japanese carrier fighters and bombers had attacked an airfield in Mindanao, the southernmost island in the Philippine archipelago. (The largely self-governing Philippines was a U.S. territory from 1898 to 1946.) Soon the Commanding General, United States Armed Forces in the Far East was notified of more strikes by enemy bombers to the north, on Luzon, the largest, most populous island where the Philippine capital, Manila, was located.

Later in the day, 50 miles/80 km north of Manila at Clark Field, much of MacArthur’s puny air force of bombers and fighters became twisted burning metal, having served as sitting ducks for 200 Japanese Zeros and Mitsubishi bombers flying out of Japanese-occupied Formosa (Taiwan), the Chinese island 500 miles/805 km to the north. Instead of acknowledging that his air force has been caught flat-footed on the ground (it was lunch hour, pilots were in the mess hall, and their planes were being fueled), MacArthur in a report to Army Air Forces Chief of Staff Hap Arnold in Washington, D.C., ascribed the disaster to “the overwhelming superiority of enemy force.” Compounding the disaster was the absence of any spare parts on the islands to repair salvageable aircraft.

Two days later, on this date, December 10, 1941, the first elements of Lt. Gen. Masaharu Homma’s Japanese 14th Army began splashing ashore at Luzon’s Lingayen Gulf, 100 miles/161 km north of Manila; more men and equipment followed on December 22, with minimal resistance encountered. Also on December 10 Japanese landings near the southern tip of Luzon seemed intent on thwarting any American reinforcements from reaching Manila from the south. In fact, a Philippines-bound convoy of 7 cargo ships carrying 4,600 men and much-need war material, dispatched from Pearl Harbor on November 29 under escort of a heavy cruiser, was diverted in mid-ocean to Brisbane, Australia, to avoid Japanese naval and air attacks. No other effort to resupply the Philippines was carried out.

On December 24, Japanese landings at Lamon Bay on Luzon’s east coast, a 50‑mile/80‑kilometer forced march from the capital, effectively cut off Southern Luzon from Manila. Despairing of overseas reinforcements and outmatched by Japanese air and naval superiority, MacArthur on Christmas Eve chose to abandon efforts to defend Manila, asking Philippine President Manuel L. Quezon to proclaim his capital an “open city” (i.e., a demilitarized zone) to “spare the Metropolitan area from possible ravages of attack.” (Manila had already been heavily bombed for 2 days.) On the back foot, MacArthur ordered his troops to “retire” (MacArthur’s euphemism) to the mountainous, thickly forested Bataan Peninsula, a 100‑mile/161‑kilometer-long, 30‑mile/48‑kilometer-wide dead-end land mass that forms the western side of Manila Bay. This they reached in January 1942, trapped like a cat in a sack in the words of one of Homma’s generals.

Japanese units followed the Allied defenders into the peninsula on January 2. The beleaguered garrison on Bataan held out until April 9, and troops on the tadpole-shaped “rock” of Corregidor in Manila Bay held out until May 6. It was the single-largest defeat in American military history, matched only by the British surrender of their island fortress, Singapore, on the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula on February 15, 1942. Nearly 80,000 U.S. and Filipino troops were sent into a cruel captivity, many of them dying on the subsequent “death march” out of Bataan. MacArthur, who was personally ordered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in late-February to leave Corregidor to assume command of Allied forces in Australia, promised Filipinos, “I shall return,” which he famously did before photographers and the news media on October 20, 1944, striding confidently through knee-deep surf toward the beach on Leyte Island.

Japanese Conquest of the Philippines, December 8, 1941, to May 6, 1942

|  |

Left: Gen. Douglas MacArthur, commander of the United States Army Forces in the Far East, and, to his right, Maj. Gen. Jonathan M. “Skinny” Wainwright, October 10, 1941. The USAFFE comprised 4 tactical commands and were a mixed force of U.S. and Filipino non-combat-experienced regular, national guard, constabulary, and newly created Commonwealth units. Wainwright, senior field commander of the American and Filipino forces, commanded the North Luzon Force, which defended both the most likely sites for Japanese amphibious attacks and the Central Luzon plain.

![]()

Right: Brushing off ineffective American resistance, Japanese Lt. Gen. Masaharu Homma, 14th Army Commander, came ashore at Lingayen Gulf, Luzon Island, on December 24, 1941. On November 6, 1941—a month and a day before the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor—Homma’s 14th Army, 1 of 4 corps-equivalent armies comprising Japan’s Southern Expeditionary Army Group, was formed for the specific task of invading and subduing the Philippines in 2 months. Within days of landing, Homma had 43,000 troops in position and poised to besiege Manila, 100 miles/161 km to the south.

|  |

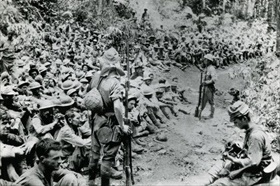

Left: The “Battling Bastards of Bataan,” U.S. and Filipino POWs after their surrender on Bataan Peninsula on April 9, 1942. (American holdouts embraced the title after MacArthur, his wife and 4‑year-old son, and some of his staff “abandoned” the Philippines in a PT boat on the night of March 10, 1942.) The Japanese victory following the Battle of Bataan (January 7 to April 9, 1942) hastened the fall of the thousand-acre/405‑hectare bastion of Corregidor Island, 2 miles/3.2 km away, a month later. More than 60,000 Filipino and 15,000 American prisoners of war—exhausted, starved, and sickened with dysentery, malaria, scurvy, hookworm, and beriberi—were forced into the infamous Bataan Death March. (Filipinos commemorate the anniversary of the march every April 9 as “Araw ng Kagitingan,” or Day of Valor.) MacArthur largely blamed the tiny U.S. Navy’s Asiatic Fleet, which withdrew from the Philippines (per plan!) on December 26, 1941, for the Japanese victory in 1942. The painful truth was, the efforts required of the nation to regain its strategic equilibrium following the shocking December 7 disaster at Pearl Harbor, plus the uncertainty of what lay in store in the European theater of war and elsewhere in Southeast Asia, reduced MacArthur’s doomed Philippine command to a tactical sideshow. Sideshow or not, for months it remained the only place Americans were actively fighting an enemy power.

![]()

Right: Surrender of U.S. forces at the Malinta Tunnel on Corregidor, May 6, 1942. The Battle of Corregidor (May 5–6, 1942) was the culmination of the Japanese campaign for the conquest of the Philippines. Corregidor, with its network of long, dank tunnels and formidable array of defensive armament, along with the fortifications across the entrance to Manila Bay, was the remaining obstacle to Homma’s 14th Japanese Army, reinforced on April 3 with fresh divisions from mainland China, the Dutch East Indies, and Malaya. Corregidor’s 56 big Coastal Artillery guns and mortars and 3 fortified neighboring islets denied the Japanese the use of Manila Bay, but the Japanese Army brought heavy artillery to the southern end of Bataan and proceeded to block Corregidor from any sources of food and fresh water. On May 6, 1942, Japanese troops forced the surrender of the last American and Filipino holdouts, which were under the command of MacArthur’s man-on-the-spot in the Philippines, Lt. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright. Skinny in build like his nickname suggested and malnourished from 3 years of mistreatment during enemy captivity, Wainwright would be present aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945, when a Japanese delegation signed their nation’s Instrument of Surrender.

|  |

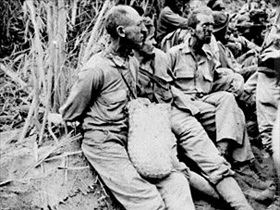

Above: U.S. prisoners of war on the “death march” from Bataan to their prison camps, April 9–17, 1942 (left photo). Homma’s 14th Area Army was responsible for the harrowing 80‑mile/129‑kilometer forced march of U.S. and Filipino POWs following Bataan’s surrender. In April’s searing heat and sunshine the Bataan Death March was accompanied by widespread mistreatment (the death-march guards, themselves thirsty and hungry, stripped many of their charges of their canteens and food rations), verbal and physical abuse (berated their captives for surrendering; applying beatings and bayoneting), and murder by “cleanup crews” who killed captives too exhausted to continue (right photo). (The POWs had survived on quarter rations or less before surrendering to the enemy, their protein needs partially supplied by meat from horses, mules, and monkeys.) An estimated 5,000 Filipinos and 750 Americans (one estimate puts the U.S. figure as high as 5,000) perished on the arduous trek before they could reach their destination. Over the next 2 months more than 16,000 captives, including 1,600 Americans, succumbed to starvation, disease, and brutality in the Japanese secondary internment area at Camp Cabanatuan. Homma, after being convicted by the postwar U.S. military tribunal for war crimes in the Philippines, was executed by firing squad. In his role as Supreme Allied Commander of the Pacific Theater, MacArthur approved the tribunal’s findings of guilt and Homma’s execution.

|

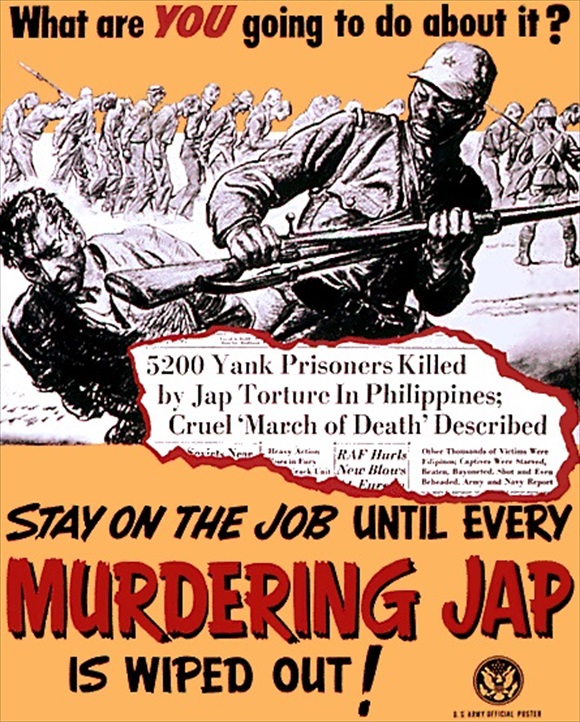

Above: The Bataan Death March and other Japanese actions were used to arouse fury in the United States, as reflected in this U.S. Army poster. Interestingly, it wasn’t until January 27, 1944, that the U.S. government informed the public about the death march. U.S. and Filipino prisoners of war who survived the death march suffered 41 months of unparalleled cruelty and savagery during captivity.

Japanese Invasion of the Philippines, 1941–1942

![]()

World War II was the single most devastating and horrific event in the history of the world, causing the death of some 70 million people, reshaping the political map of the twentieth century and ushering in a new era of world history. Every day The Daily Chronicles brings you a new story from the annals of World War II with a vision to preserve the memory of those who suffered in the greatest military conflict the world has ever seen.

World War II was the single most devastating and horrific event in the history of the world, causing the death of some 70 million people, reshaping the political map of the twentieth century and ushering in a new era of world history. Every day The Daily Chronicles brings you a new story from the annals of World War II with a vision to preserve the memory of those who suffered in the greatest military conflict the world has ever seen. History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click