U.S. HOSPITAL TRAINS TO CONVEY INJURED GIs TO CARE CENTERS/HOME

Washington, D.C • December 16, 1940

The late 1930s saw storm clouds and thunder rumble over both mainland China and Europe. The 8‑year Second Sino-Japanese war erupted in July 1937, shattering an uneasy truce between the Nationalist Chinese and the Empire of Japan. In mid-March the following year events in Europe threatened full-scale war when Nazi Germany annexed Austria (Anschluss) and invaded the tinder box country of Czechoslovakia. Then lightning stuck Poland on September 1, 1939, when Adolf Hitler’s blitzkrieg rolled up Poland’s army in just over a month. On September 3, 1939, Great Britain and France, followed within days by Canada and much of the British Commonwealth, declared war on Nazi Germany. Only 2 oceanic moats and America’s declared neutrality protected the country from being burned by conflagrations originating thousands of miles/kilometers away.

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, with cool calculation, watched the sad happenings beyond his nation’s borders. He worked tirelessly to successfully repeal the isolationist Neutrality Acts (1935–1939), which limited his administration’s ability to aid democratic Britain and France against a fascist Germany arming to the teeth. He approved the “destroyers for bases” deal with Great Britain in September 1940 through which the U.S. transferred 50 World War I‑era destroyers to the British Navy in exchange for leases for British naval and air bases in both the Eastern and Western Hemispheres. He signed the Lend-Lease Act in March 1941, a policy under which the U.S. supplied the United Kingdom, France, China, the Soviet Union, and other Allied nations with food, oil, and essential materiel free of charge between 1941 and 1945.

It was anybody’s guess when the U.S. would become a belligerent. An educated guess, however, was sooner than later. The establishment of new U.S. military bases in the North Atlantic (Iceland, Northern Ireland, and Great Britain), the Caribbean, and South America, along with extant bases in U.S. possessions in the western and central Pacific Ocean area, weighed on the minds of military brass. The passage of selective service legislation in September 1940 added to the pressure of devising a successful, all-encompassing plan for moving likely American casualties from ports of entry on the east, west, and gulf coasts to general hospitals, specialty care, and rehabilitation centers closest to the soldiers’ hometowns whenever possible. The last time similar contingency planning had occurred was during the First World War.

In the late interwar years planning for new U.S. Army hospital trains and reinventing and reimagining the First World War’s domestic “ambulance trains” gained momentum. In September 1940 the Surgeon General’s Office suggested the Army try converting commercial Pullman sleeper cars to transport wounded ambulatory and litter (stretcher) patients from American ports to care facilities throughout the country. On this date, December 16, 1940, Army Engineers ordered enough 20‑ton sleeper cars to test some for use in Army hospital trains. When the U.S. entered the global war on December 8, 1941, the nation had just 6 functioning Army hospital train cars.

Hospital trains were mini-hospitals on rails that provided casualties of war in need of either emergency treatment immediately or expert care or both while they were being transported to permanent medical facilities. Construction of new hospital cars was expanded to the greatest extent possible. By the end of the war the nation had 380 purpose-built cars (see photo essay below). But the logistics of moving patients around the country by rail was exceedingly complex. So too was staffing these trains and cars. Hospital trains typically carried 190 patients and were staffed by 6 doctors, 3 administrative officers, 5 nurses, and 57 enlisted men who served as medics, cooks, and similarly essential personnel. Nurses assumed day-to-day care of patients and passed orders on to the medics.

Bringing the Wounded Home: Hospital Trains, 1940–1945

|

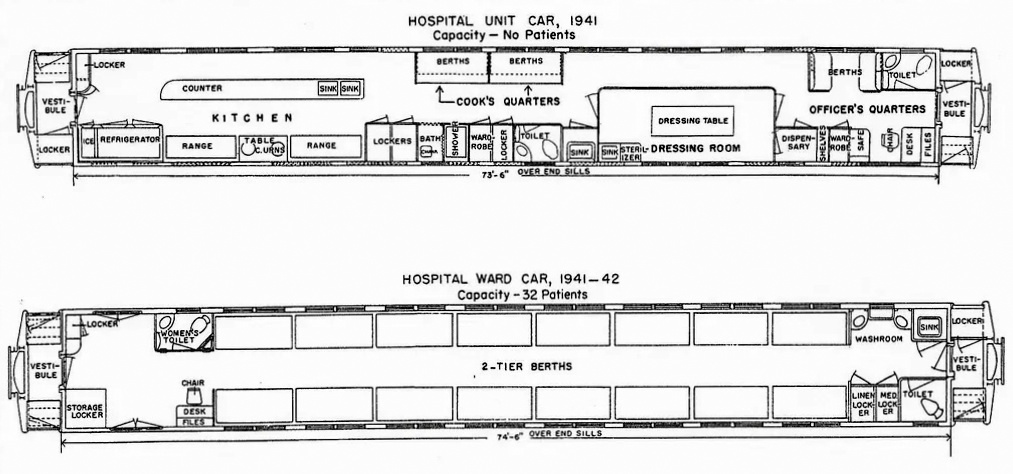

Above: Floor plans of purpose-built (not converted) hospital unit and ward cars, 1941–1942. The U.S. Army and Office of the Surgeon General settled on 4 (later 3) types of hospital cars: unit, ward, ward dressing (dropped), and kitchen. In 1944 the unit car, measuring 84.5 ft./25.8 m long, became self-contained, with berths for upward of 36 wounded soldiers, a kitchen, a receiving room that functioned as a pharmacy, an administrative office and emergency operating room, 2 toilets, and a storage area. The unit car was air-conditioned—a luxury at the time. The 1944 unit car could be detached from military trains (troop and hospital trains) and attached to commercial trains without jeopardizing patient care. By the end of World War II, the U.S. Army owned 202 unit cars, 80 ward cars, 38 ward dressing cars, and 60 kitchen cars.

|  |

Left: A photo from early in the war shows what had been a commercial Pullman sleeper converted into a hospital ward car. Securing space on domestic railroad lines to carry injured troops in Pullman sleeper cars could take as long as 2 weeks when it was tried. Even when space was available, it was a struggle to load litter patients into the converted Pullmans (sometimes through windows) and negotiate the outside vestibules and narrow aisles inside.

![]()

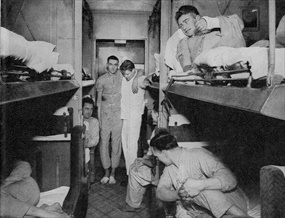

Right: Cramped late‑war 3‑tiered bunk beds on either side of the aisle accommodated 24–36 patients. Bunk beds had springs and folded up, turning into tables for cardplayers. Litter patients lying on stretchers suffered because they had no cushioning or padding under them. For litter patients train journeys were agonizing. By way of example, in France litter patients faced a journey of up to 50 hours from Paris to English Channel embarkation ports. Any journey in a hospital train inevitably turned into one or a mixture of boredom, camaraderie, humor, emotional trauma, and tension.

|  |

Left: A smiling Private Thomas M. Ware on a hospital train at Hampton Roads Pier in Newport News, Virginia. During a German air raid in Italy on April 26, 1944, the 19‑year-old Ware suffered a severe shrapnel wound to his leg. The wound turned gangrenous and led to the lower third of his leg and his foot being amputated. Ware was discharged from the U.S. Army on December 23, 1944.

![]()

Right: Demonstration illustrating a stretcher patient being helped through a double door and into a British hospital train ward car. The British, Free French, Germans, and Americans operated hospital trains and cars that evacuated soldiers from combat zones to more “specialized” medical facilities outside the theater of combat operations (about 50 miles/80 km behind the front lines). A British hospital train typically consisted of 14 cars, 7 of which were ward cars equipped to accommodate 250–317 casualties, depending on whether they were litter, ambulatory, or PTSD or other psychiatric cases. The pharmacy car was the most important component, possessing an operating room with all the necessary equipment; the rest of the hospital train consisted of a kitchen car and sleeping quarters for the medical staff. By September 1, 1943, 15 hospital trains were operational in the United Kingdom; another 10 were eventually operational overseas moving the wounded from so-called transit hospitals to general hospitals where staff took care of their patients’ specific needs.

U.S. World War II Hospital Trains

![]()

World War II was the single most devastating and horrific event in the history of the world, causing the death of some 70 million people, reshaping the political map of the twentieth century and ushering in a new era of world history. Every day The Daily Chronicles brings you a new story from the annals of World War II with a vision to preserve the memory of those who suffered in the greatest military conflict the world has ever seen.

World War II was the single most devastating and horrific event in the history of the world, causing the death of some 70 million people, reshaping the political map of the twentieth century and ushering in a new era of world history. Every day The Daily Chronicles brings you a new story from the annals of World War II with a vision to preserve the memory of those who suffered in the greatest military conflict the world has ever seen. History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click