CHERBOURG’S CAPTURE TO REPLACE LOST MULBERRY HARBOR

Cherbourg, France • June 26, 1944

On June 19–22, 1944, a violent gale featuring 332‑knot/59‑km/h winds hit the 2 huge Mulberry artificial harbors that the Allies had built in England, towed across the English Channel under danger of wind, weather, and enemy air attack, and planted off the Normandy invasion beaches, one off Omaha, the other off Gold, on D‑Day+8 (June 14). Measuring 2 miles/3.2 km long by 1 mile/1.6 km wide, the prefabricated harbors with their sheltered waters and their pontoon-supported ramps to the beaches were intended to deliver greater supplies of men, armor, vehicles, and munitions than landing craft could. Indeed, in just 5 days between June 14 and 18 the Mulberry harbor off Omaha Beach had moved a daily average of over 8,500 tons of cargo ashore. Allied planners appeared correct in their conviction that the artificial harbors, each of which could unload 7 ships simultaneously, were essential for the success of Operation Overlord.

The June 1944 gale, the worst to hit the Channel in 40 years, inflicted losses greater than the enemy had been able to exact on the Allies: 800 ships were sunk or beached and more than 140,000 tons of supplies destroyed. Gone was the Mulberry harbor at Omaha Beach—deemed irreparable. The other one at Arromanches (center of the Gold Beach landing zone), better protected, was nevertheless damaged. The setback was colossal. GIs were down to 2 days of ammunition. The nearest replacement harbor, Cherbourg, at the tip of the Cotentin Peninsula, was 40 miles/64 km northwest of the smashed Mulberry harbor at Omaha Beach and firmly in German hands.

On this date, June 26, 1944, U.S. infantry divisions, aided by P‑47 Thunderbolt dive-bombers, captured the heavily defended hilltop bastion that dominated Cherbourg and its harbor, Fort du Roule. Below the fort was a battery of 105 mm guns in casemates built into the hillside. The city’s 21,000‑man garrison under Maj. Gen. Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben, some of whom were Osttruppen “volunteers” (actually Polish and Soviet former POWs in German uniforms), surrendered piecemeal due to communications breakdowns between Wehrmacht (German armed forces) units. Allied mopping-up operations on nearby Cap de la Hague Peninsula were completed by July 1, which was also the last day the enemy could conceivably have reversed their sagging fortunes in Normandy.

The Allied victory was tempered by the discovery that the deep-water harbor of Cherbourg, suddenly so critical to sustain and reinforce Allied forces in Normandy, had been systematically wrecked by German engineers starting on June 7, the day after D‑Day. American ingenuity provided a temporary solution to finding a way to get food, stores, and ammunition off ships anchored outside Cherbourg’s harbor and onto onshore trucks: Omaha’s and Utah’s DUKWs. DUKWs (pronounced “ducks”) were 6‑wheel-drive amphibious modifications of the 2½‑ton cargo truck used by U.S. and Allied armed services. DUKWs accepted 5–7 tons cargo lowered by ship’s booms, swam back under constant nighttime aerial strafing and bombing to improvised ramps on Cherbourg’s foreshore, and were unloaded near the city’s statue of Napoleon on horseback by mobile cranes or other DUKWs fitted with A‑frames. The unloading area became known to U.S. servicemen as “Nap and the Ducks.” A little more than 21,000 DUWKs were manufactured before production ended in 1945.

Cherbourg’s main harbor basins were not cleared until September 21, causing a logjam of materiel and vehicles and a shortage of fuel that forced the Allied advance eastward to sputter out near the German frontier. Von Schlieben’s efficient demolition of Cherbourg’s harbor bought the Third Reich just 3 extra months before Germany’s apocalyptic collapse in April and May 1945.

The Fall of Cherbourg, France, Late June 1944

|  |

Left: U.S. soldiers dodge enemy fire on Cherbourg’s battle-ravaged streets. Hitler, who made his last visit to France on June 16–17, 1944, on the eve of Cherbourg’s capture, ordered Maj. Gen. von Schlieben to leave “Fortress Cherbourg,” population 39,000, a “field of ruins.” It was typical for Hitler to personally appoint each fortress commandant to his post; each was required to sign and return a sworn affidavit stating that he would hold his fortress to the last man, no matter how woefully inadequate his defense force might be. The penalty for falling short was implied in the very nature of the affidavit. Von Schlieben’s boss 2 rungs up, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel of Army Group B, commanded the general “to fight until the last cartridge in accordance with the order from the Fuehrer.” By then, though, Rommel and his boss, Commander-in-Chief West Field Marshal Gert von Rundstedt, had come to recognize the hopelessness of defending Cherbourg and the rest of Northwest France and went so far as to tell Hitler that. On July 1 Hitler relieved von Rundstedt of his command. Rommel had the temerity to advise Hitler to end the war as soon as possible.

![]()

Right: Fort du Roule garrisoned Cherbourg’s southern approaches. Exceptional bravery by American infantrymen crumbled the fort’s defenses, and white flags popped up everywhere. On June 26, von Schlieben was captured at his makeshift underground headquarters after U.S. tank destroyers fired into his bunker.

|  |

Left: The city’s German defenders, which had originally held Utah Beach, were mostly overaged, undertrained, and verbunkert (suffering from bunker paralysis), as von Schlieben complained to Rommel before surrendering the city to U.S. Lt. Gen. J. Lawton “Lightning Joe” Collins, commander of the U.S. VII Corps. Cherbourg’s quick capitulation to the Allies, only 20 days after D‑Day, shook Hitler to his core, notwithstanding Rommel’s prediction that it was bound to happen.

![]()

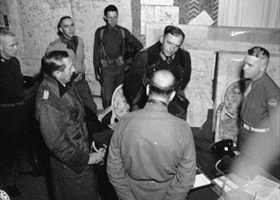

Right: For losing Cherbourg, one of the largest ports in France, von Schlieben was ridiculed in Nazi circles as a poor specimen of what a commander should be. Fifteen months earlier then-Colonel von Schlieben was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross for bravery before the enemy and for excellent merits in commanding troops on the Eastern Front. On June 23, 1944, Rommel conferred the post of Commandant of “Fortress Cherbourg” on his Seventh Army’s 709th divisional commander, Maj. Gen. von Schlieben. Poor von Schlieben’s fate was similar to that of Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus, hapless defender of Stalingrad, as Hitler pursued his maniacal search for scapegoats following one Wehrmacht loss after another. Left to right in the photo: Rear Adm. Walter Hennecke, commander of the sea defenses throughout Normandy; von Schlieben (middle, facing camera); and Collins during the official capitulation of German forces in Cherbourg.

Contemporary Newsreel Footage of the Allied Drive to Take Cherbourg, June 1944

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click