JAPAN UNAFRAID OF WAR WITH U.S.

Tokyo, Japan • July 2, 1941

On this date in 1941, in an Imperial Conference of high-level Japanese officials (Gozen Kaigi), Shōwa Emperor Hirohito sanctioned the military seizure of bases in the south of Vichy French Indochina (present-day Vietnam). It was in keeping with Japan’s so-far unsuccessful attempts to force the surrender of their Chinese enemy, Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government, by severing land links with its chief backers, the United States and Great Britain, that ran through the French colony. Only 10 months earlier Japanese forces had gained access to 3 airfields and permission to maintain a 6,000‑man garrison in Northern French Indochina.

Authorized by the July 2 Imperial Conference, Japan moved its armed forces into Southern French Indochina on July 25, 1941, and announced a protectorate over the whole of the French colony (today’s Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia). Tokyo did this in defiance of a U.S. State Department warning the previous September against any attempt to change the status of French Indochina after the mother country had succumbed to Japan’s Axis ally, Nazi Germany. In carrying out their ground and naval deployments in Southern French Indochina, the Japanese government and Japan’s Army and Naval General Staffs had decided that the nation would not be deterred by the possibility of becoming involved in a war with the U.S. and Great Britain. Emperor Hirohito, in giving ceremonial sanction to his military’s plan to occupy all of French Indochina, accepted the possibility of the action sparking a war with West that he wished to avoid.

The next day, July 26, 1941, an angry Franklin D. Roosevelt issued an executive order to freeze all Japanese assets in the U.S., totaling $130 million dollars, in effect bringing all financial and import and export trade transactions in which Japanese interests were involved under U.S. government control. Oil-rich Netherlands East Indies (present-day Indonesia) followed the U.S. lead by freezing Japanese assets and oil exports. Great Britain, Australia, and New Zealand likewise froze Japanese assets, while Great Britain went further by announcing its intention to end bilateral commerce.

Early in September 1941 Japanese officials gave their diplomats until October to reverse the policy of the Western powers. At an Imperial Conference on November 5, 1941, Gen. Hideki Tōjō—war minister, home minister, and since October 17 prime minister—said Japan must be prepared to go to war with the West, with the time for military action tentatively set for December 1, less than a month away, if diplomacy with the U.S. and European colonial powers failed to improve relations and reverse economic sanctions. Just before the December 1 deadline Kichisaburō Nomura, Japan’s ambassador to Washington, reported failing to overcome the Roosevelt administration’s insistence on Japan’s withdrawing its armed forces from China and halting its aggressive Southeast Asian incursions before the U.S. would resume trade with his country.

On December 1 another Imperial Conference officially sanctioned war against the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands. Continued talks in Washington to heal the breach between the two nations were a smokescreen for Vice-Adm. Chūichi Nagumo’s Striking Force of 6 aircraft carriers as they made their way to the Hawaiian Islands and took up positions on December 4, 1941, 250 miles/402 kilometers northwest of their designated targets: the U.S. Pacific Fleet riding at anchor at Pearl Harbor and U.S. aircraft parked smartly at Hickman Field.

![]()

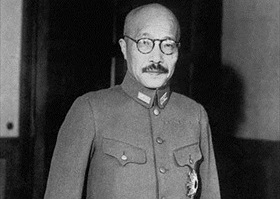

Emperor Hirohito and His Wartime Prime Minister, Gen. Hideki Tōjō

|  |

Left: Wartime photograph of Emperor Hirohito, seated in middle, as presiding head of an Imperial Conference (Gozen Kaigi). Convened by the Japanese government in the presence of the emperor at his palace, Imperial Conferences were extraconstitutional conferences that focused on foreign affairs of grave national importance. In the July 2, 1941, Imperial Conference, Hirohito, despite his doubts and reservations, gave ceremonial sanction to the military’s plan to seize French Indochina. (Although ceremonial, the emperor’s sanctions rendered decisions of Imperial Conferences sacred state decisions regardless of Hirohito’s personal view on the matter.) At the all-important Imperial Conference on December 1, 1941, Hirohito sanctioned a war with the West he did not want, partly due to the enormous pressure the Japanese high command exerted on him, and partly due to the failure of diplomatic negotiations with the U.S. in Washington.

![]()

Right: Tōjō in military uniform. On July 22, 1940, Tōjō was appointed Army Minister. During most of the Pacific War, from October 17, 1941 to July 22, 1944, he served as Prime Minister of Japan. In that capacity he was directly responsible for the attack on Pearl Harbor. Tōjō was forced to resign from office following the disclosure of Japan’s loss of Saipan in the Mariana Islands to U.S. Marines and soldiers. After the war Tōjō was arrested, sentenced to death for war crimes during the Tokyo Trials, and hanged on December 23, 1948.

History’s Verdict: Japanese Emperor Hirohito Documentary

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click