JAPANESE, CHINESE CLASH AT MARCO POLO BRIDGE

Wanping, Near Beijing, China • July 7, 1937

The major turning point that ultimately led to Japan’s disastrous war with the United States and its European allies in December 1941 occurred late on this date, July 7, 1937, and into the next. Japanese and Chinese soldiers clashed at a bridge over the Yongding River near Wanping, a walled town 10–12 miles/16–19 kilometers southwest of Beijing, China’s former capital and since 1949 the country’s current capital. Years before, beginning in 1931, top Japanese civilian and military authorities, including their sovereign and commander in chief of the Imperial Japanese Army Emperor Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa), had retroactively sanctioned the seizure of Manchuria by local army commanders stationed in China’s northeast following the so-called Mukden Incident. From this Manchurian springboard—a puppet state named Manchukuo hatched by Japan’s China-based Kwantung Army—the Japanese by the summer of 1937 had expanded the reach of their armed forces southward into China proper to a point where their soldiers now surrounded Beijing and Tianjin (Tientsin), the latter a major seaport and water gateway to Beijing.

Local Japanese commanders only needed a casus belli to justify seizing Beijing and Tianjin. They found it at an 11‑arch granite bridge named after the Italian explorer, Marco Polo. On the night of July 7/8 a Japanese rifle company stationed outside Beijing conducted unannounced training exercises near Wanping and exchanged gunfire with Chinese forces. Hours later Japanese soldiers attempted to breach Wanping’s walled defenses to search for an allegedly missing soldier (the story is murky) but were beaten back. Around 4 a.m. reinforcements from both sides poured into the area. An hour or so later Japanese forces opened fire and attacked the nearby Marco Polo Bridge (also known as the Lugou Bridge) as well as a railway bridge to the north, part of the main rail line west of Beijing that held considerable strategic value for both sides.

Despite efforts by senior-level diplomatic and local army commanders to defuse hostilities, which briefly included a ceasefire, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident led to more Japanese-contrived clashes between the opposing armies (Japanese heavy artillery shelled Wanping on July 14), as each side mobilized reinforcements. By the start of the next month a clear-cut Japanese victory had emerged in the Battle of Beiping (Beijing)-Tianjin (early July to early August 1937). That battle, or rather series of battles that involved heavy casualties and was backed by Japanese tanks, warplanes, and naval forces, is recognized as the start of China’s War of Resistance (1937–1945), or as it is known in the West, the Second Sino-Japanese War.

Incidents on the Path to the Second Sino-Japanese War, 1937–1945

|

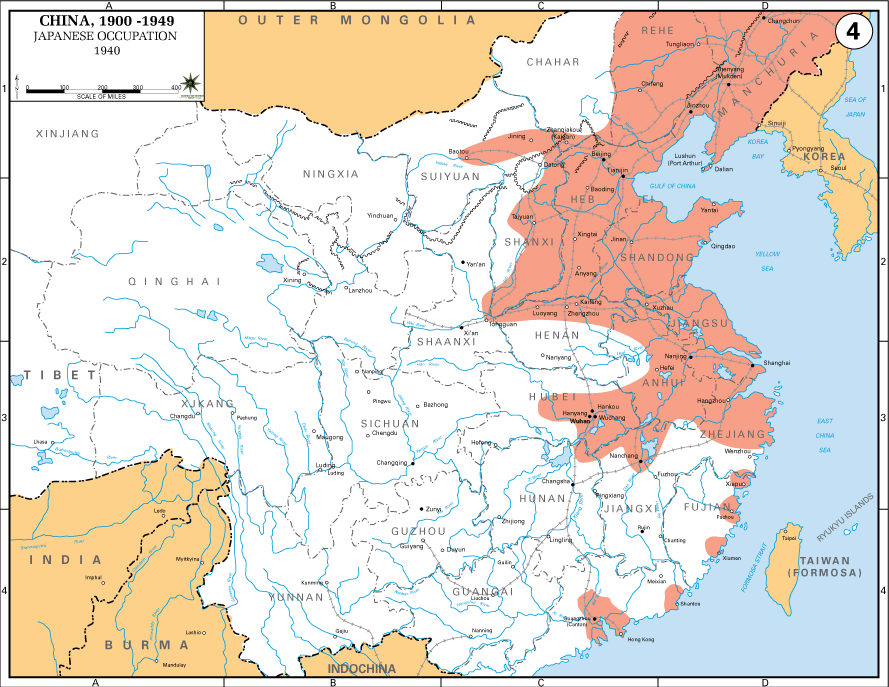

Above: Map of China, 1940, showing the extent of Japanese imperialism (in burgundy). In its quest for an empire in Asia, Japan seized Taiwan in 1895, declared Korea an imperial protectorate in 1905, and invaded Manchuria (Manchukuo) in China’s northeast in 1931. The decision of Japan’s modernized military and civilian leadership to expand Japanese military activity along the entire Chinese seaboard and work inland, after closing the door to further diplomatic engagement with the Chinese government in January 1938, dragged Japan into an unwinnable war. The outcome was Japan losing all its territorial gains since the start of the First Sino-Japanese War in 1931.

|  |

Left: Japanese cavalry entering Mukden (Shenyang), Manchuria, September 18, 1931. Japan’s Kwantung Army on the Chinese mainland fabricated a bombing incident on a tiny portion of the Japanese-owned South Manchuria Railway as a pretext to occupy Manchuria, a semi-independent province of China, and other areas in Northeastern China like Jehol (1933), which they claimed was part of Manchuria. Manchuria was rich in mineral and agricultural resources. Most Westerners believed the Mukden Incident (aka Manchurian Incident), although coming on top of other Sino-Japanese armed clashes (so-called “incidents”), was way overblown and should not have led to Japan’s takeover of Manchuria.

![]()

Right: Japanese infantrymen celebrate their seizure of the Marco Polo Bridge. Manchukuo became the launch pad for further Japanese hostile acts in China. Localized armed clashes resulted in outlying provinces being annexed into Manchukuo or turned into buffer zones, effectively under Japanese occupation. By the start of 1937 all the areas north, east, and west of the large Chinese city of Beijing were controlled by Japan. On July 7–8, 1937, the Japanese provoked another “incident” at the Marco Polo Bridge southwest of Beijing, as well as at a railroad bridge to the southeast of the city. The railroad bridge over the Yongding River was a choke point on the Beijing-Wuhan rail line and the only passage linking Beijing to non-Japanese-controlled areas to the south.

_1937_280x193.jpg) |  |

Left: Heightened tensions following the Marco Polo bridge skirmish led directly to Japan’s full-scale invasion of China in the Second Sino-Japanese War, beginning with the Battle of Beijing-Tianjin (early July to early August 1937) and the Battle of Shanghai (August 13 to November 26, 1937). In this photo Japanese troops are shown passing from Beijing into the Tartar City through Chenmen (Qianmen, also known as Zhengyangmen), the main gate leading to the palaces in the Forbidden City, sometime in mid-August 1937.

![]()

Right: Japanese marines celebrate their successful landing near Shanghai in mid-August. Approximately 200,000 Chinese and 70,000 Japanese died during Japan’s 3‑month attempt to take Shanghai, South China’s industrial and economic center. Shanghai was the first of 22 major engagements between the Chinese Nationalists under their leader Chiang Kai-shek. Japan’s War Minister Hajime Sugiyama had foolishly predicted the Chinese would be crushed “in about a month” and sue for peace. Sugiyama’s dual predictions, which Emperor Hirohito accepted, were tragically off the mark. Of course, in the end it was Japan and Hirohito who sued for peace. The Chinese War of Resistance lasted nearly 8 years, and it accounted for most of the military and civilian casualties in the entire Pacific War. The more the Japanese plunged deeper into the Chinese heartland, trying to find and win that decisive, but elusive, victory, the more the Chinese people rallied to resist Japan’s cruel and ever-increasing aggression. Sadly, over 4 million Chinese and Japanese military personnel and anywhere from 10 to 25 million Chinese civilians died from war-related violence, famine, and other causes.

July 1937 Marco Polo Bridge Incident Ignites Second Sino-Japanese War and by Extension World War II (Skip first 70 seconds)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click