JAPANESE CAPITAL FIREBOMBED

Tokyo, Japan • February 24, 1945

The first appearance over Japan in June 1944 of the massive 4‑engine B‑29 bomber—with its service ceiling of 33,000 ft/9,144 m, an operational range of over 3,200 nautical miles/5,926 km, and a maximum takeoff weight of 133,500 lb/60,555 kg—meant that the enemy’s Home Islands were squarely in the crosshairs of the war’s deadliest delivery system. On this date, February 24, 1945, the Japanese capital witnessed its first incendiary raid when 174 China-based B‑29 Superfortresses returned and destroyed roughly 1 sq mile/2.6 sq km of the city and approximately 28,000 buildings.

The blast-and-burn campaign against Japan’s highly combustible cities was the brainchild of Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay. Having previously served in the U.S. Eighth Air Force in Europe, LeMay saw how the incendiary air campaign over German targets had played out, and he brought the concept with him when he assumed command of B‑29 operations, first in China, and then of all B‑29 operations in the Pacific.

The transplanted LeMay made a radical departure from the current high-altitude, daytime “precision” bombing practices using conventional ordnance on Japanese targets—practices that so far had been unable to devastate the enemy’s war industry, cause general economic chaos, and destroy civilian morale. On the night of March 9/10, 1945, LeMay sent his B‑29 armada loaded with napalm (jellied gasoline) bombs over Tokyo at low altitude. Operation Meetinghouse (“Meetinghouse” being code for the urban area of the Japanese capital) was the single most destructive bombing raid in history: 100,000 people died, 25 percent of the city was destroyed (267,000 buildings)—equivalent in size to half of New York’s Manhattan Island—and more than a million inhabitants were made homeless.

In the ensuing 5 months, low-level nighttime area bombing with napalm bombs destroyed or heavily damaged 67 Japanese cities. In more than 31,300 B‑29 sorties over the Home Islands, just 74 Superfortresses were known to have been lost wholly to enemy interceptors (a mere 0.24 percent of effective sorties) and perhaps 20 more in concert with flak guns. Many more Superforts were lost in accidents during takeoffs and landings.

The most famous Superfortress was named Enola Gay, which on a separate combat mission led by Col. Paul Tibbetts dropped a high-explosive bomb with the force of 12.5 kilotons of TNT—the first of 2 atomic bombs—that led to Japan’s capitulation on August 15, 1945.

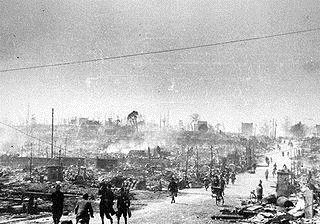

Firebombing Tokyo, 1945

|  |

Left: Tokyo after the massive saturation firebombing on the night of March 9/10, 1945, the single most destructive raid in military aviation history. Over 50 percent of Tokyo was reduced to ashes by the end of World War II.

![]()

Right: Tokyo after the surprise March 1945 nighttime bombing raid, which left more than 1 million residents homeless and the city’s industrial productivity cut in half. LeMay had bet his reputation that Japan, by this date, had few night fighters available, so that the U.S. strike force, maxed out with bombs (each B‑29 was 13,000 lb/5,897 kg overweight!) and flying at low altitude (5,600 ft/1,707 m), would not be subjected to normal (i.e., daytime) air-to-air opposition. Tokyo was again razed on May 23 and 25, leaving 3 million residents now homeless. In May 1945 alone one‑seventh of Japan’s built-up urban area—a staggering 94 sq miles/243 sq km—had been devastated in the firebombing campaign.

|  |

Left: Citizens walk through a still-smoldering, rubble-strewn neighborhood following the March 1945 firebombing. Emperor Hirohito’s tour of the destroyed areas of Tokyo in March is said to have been the beginning of his personal involvement in the peace-making process.

![]()

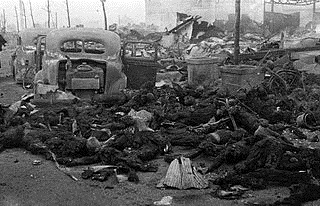

Right: Charred remains of civilians after the March 9–10, 1945, firebombing of Tokyo.

|  |

Left: Authorities try to identify the victims of Tokyo’s firebombing. Raids on Tokyo lasted until August 15, 1945, the day Japan capitulated.

![]()

Right: A “LeMay Bombing Leaflet” dropped late in the firebombing campaign, urging Japanese citizens to evacuate cities named on the leaflet and save themselves.

Operation Meetinghouse, the March 9–10, 1945, Firebombing of the Japanese Capital

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click