JAPAN CREATES CHINESE PUPPET STATE

Hsinking (Changchun), Manchukuo • February 18, 1932

The Meiji Restoration of Imperial rule in Japan in 1868 resulted in the downfall of that country’s powerful military commanders, the shoguns, and the Japanese samurai warrior class. Partly as a concession to the samurai, the Japanese government embarked on an aggressive foreign policy in Manchuria in Northeastern China and on the Korean Peninsula. The Japanese defeat of Czarist Russia over the latter’s territorial ambitions in Manchuria in 1904–1905 both bolstered Japan’s power, authority, and self-confidence in the Asia Pacific region while it sparked an upsurge in national and imperial sentiments among important sectors within Japan itself, among them the military, political parties, and the jingoistic press. The Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I, granted Japan rights and concessions in the Shantung Peninsula in Northeastern China across the Yellow Sea from Korea, a Japanese colony since 1910.

Using an argument similar to the Nazis’ mantra for Lebensraum in Eastern Europe and Fascist Italy’s spazio vitale in the Mediterranean Basin, Japanese national extremists looked west across the Sea of Japan to China for living space. (A corollary of the quest of Japanese extremists for living space for their country’s “excess population” was Hakkō ichiu, a Japanese political slogan meaning the divine right of the Empire of Japan to “unify the eight corners of the world.” The next logical step was the proclamation of a “new order in East Asia” (Tōa Shin Chitsujo) that morphed into the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” in the 1940s in which Japan assumed the axial position around which some 10 East Asian socio-political entities orbited.) On September 18, 1931, Japan’s Kwantung Army in China invaded Manchuria. Five months later on this date, February 18, 1932, the Kwantung Army, without the approval of Tokyo, established the puppet state of Manchukuo (State of the Manchus), the freewheeling Kwantung Army’s springboard for further aggression in China. In the same year the Imperial Japanese Army, with the blessings of Shōwa Emperor Hirohito (on the throne from 1926 to 1989), organized a secret research group in Manchukuo’s Pingfang district for the purpose of developing chemical and biological weapons to be used against the Chinese, Koreans, and other “inferior” peoples whose territory they, comparable to the Nazis and Fascists in Europe, intended to conquer.

Unit 731, whose Pingfang headquarters’ design was that of a lumber mill, was the most notorious of these research laboratories, where epidemic and viral diseases such as bubonic plague, typhoid, cholera, and anthrax were mass-produced. Branch units were established at Beijing, Nanjing (Nanking), Guangdong, and Singapore, which along with the main Pingfang campus employed as many as 20,000 staff members. More than 10,000 humans (euphemistically known as “logs,” pronounced maruta in Japanese) were subjects of barbarous experiments conducted in this and similar factories of death, repeatedly being forced to work to exhaustion and exposed to diseases, starvation, and vivisection. Hapless subjects included criminals, bandits, anti-Japanese partisans, political prisoners, as well as infants, children, the elderly, and pregnant women. Run by the Kwantung Army, Unit 731’s victims also included U.S., British, Dutch, Australian, and Soviet prisoners of war.

Subjects of experimentation were typically infected with particular pathogens by injection or ingesting contaminated food or water. They would be observed, their symptoms recorded, blood samples taken, organ tissue vivisected, and, following death, their bodies incinerated. Unit 731’s germ and chemical weapons programs resulted in possibly as many as 200,000 grisly deaths (to say nothing of extreme suffering) of civilians and military personnel between 1932 and 1945. In a deal struck with U.S. occupation forces, most Japanese perpetrators were never brought to justice after the war.

Japanese Puppet State Manchukuo (1932–1945) and Biological/Chemical Warfare Unit 731

|

Above: Map of of Manchukuo (Manchuria) in relation to its neighbors. The large area labeled “Japan” is the Japanese colony of Korea (1910–1945). The smaller area on the southern part of the Liaodong Peninsula in Manchuria went by the name of Kwantung Leased Territory (formerly a Russian-leased territory from 1898 to 1905), which included the militarily and economically significant ports of Lüshunkou (Port Arthur) and Dalian. In 1934 the Kwantung Army placed Puyi (Pu Yi), the last Qing emperor of China, at the city of Changchun, renaming it Hsinking or Xinjing (New Capital). Piyu (1906–1967) served as Japanese puppet emperor of Manchukuo until August 1945, when Hirohito agreed to end the Asia Pacific War.

|  |

Left: Propaganda poster promoting harmony between Japanese, Chinese, and the residents of Manchukuo. The caption says (right to left): “With the cooperation of Japan, China, and Manchukuo, the world can be in peace.”

![]()

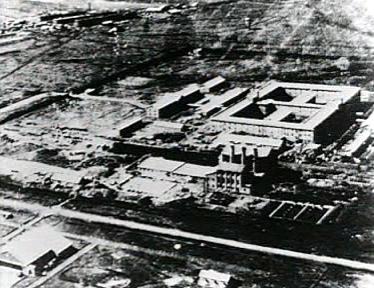

Right: Japanese Biological Warfare Unit 731 Headquarters at Pingfang, Manchukuo (Northeast China), a little over 60 miles/96 kilometers southeast of Harbin (see map). Officially known as the Epidemic Prevention and Water Purification Department of the Kwantung Army (the Japanese occupation army in Manchukuo), the sprawling complex was serviced by an airport and railroad stations. Leading Japanese medical schools assigned doctors to Unit 731, some of whom later complained of wasting the best years of their lives on medical research that could not be continued after the war. Almost 70 percent of the victims who died in at Pingfang (there were other Unit 731 installations) were Chinese, including both civilian and military. Soviets comprised close to 30 percent of the victims. Most of Pingfang was burnt by the Japanese to destroy evidence of some of the most gruesome atrocities of World War II, but the incinerator where the remains of victims were burnt remains today. Unlike war crimes associated with Nazi human experimentation, which are extremely well documented, the activities of Unit 731 are known only from the testimonies of former unit members.

Japan’s Unit 731: A Documentary on Biological and Chemical Warfare Conducted Around the Globe (WARNING: Extreme Content)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click