LEADING JAPANESE POLLED ON HOW TO END WAR

Tokyo, Japan • August 29, 1944

From the summer of 1944 to the spring of 1945, Japanese forces continued their retreat from military outposts in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Japanese losses in personnel, warships, and airplanes were minimized by frontline commanders, who exaggerated Japanese military successes against the Allied enemy in reports to Imperial Headquarters.

Emperor Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa) had long been troubled by the unfavorable direction the Pacific War had taken, especially following the Allied conquest of Saipan in the Mariana Islands and the resignation of fire-breathing Prime Minister and War Minister Gen. Hideki Tōjō in July 1944. In the wake of Japanese losses in the Philippines in early 1945, Hirohito asked seven jushin (senior statesmen), six former prime ministers and the former lord keeper of the privy seal, how Japan should bring an end to the war. Ordinarily, it was a criminal offense to talk about terminating hostilities (shūsen)—the military police could arrest anyone suspected of antiwar sentiments. In his audience with the emperor on February 14, 1945, former Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe boldly advised ending the war at the earliest possible opportunity. This might be accomplished by purging the military die-hards from positions of power, which just might allow the country to negotiate more favorable peace terms. The purge, the prince hinted, could be carried out through a formal decree by the emperor, known as a seidan, in his role as diagensui (military commander in chief).

Already by this date, August 29, 1944, some end-the-war advocates in the Imperial Japanese Navy were quietly trying to move Japan’s decision makers to wind down the war. The question was how and when. One of their chief supporters was the emperor’s brother, Prince Takamatsu, whose ultimate objective was defending Japan’s kokutai (national polity) in any peace deal with the Allies. Early peace negotiations based on a realistic assessment of Japan’s perilous prospects for staving off defeat would best preserve the kokutai, he believed. Japanese defeats on the islands of Iwo Jima and Okinawa (February 19 to June 21, 1945), the latter battle fought on Japan’s home turf, increased the influence of the peace faction (mainly Navy and civilians leaders) over that of mostly Army hardliners, among them Gen. Tōjō, while they weakened the country’s bargaining muscle.

By early March 1945 officials in the imperial palace and the Foreign Ministry had reached a tacit understanding. The emperor would endorse the government’s decision to conclude the war through an imperial seidan at the appropriate time. Operation Meetinghouse, the March 9/10, 1945, overnight onslaught by nearly 300 U.S. B‑29 heavy bombers that caused the most devastating destruction of any city during World War II, caused Hirohito, who toured his capital on March 18, to cry: “Tokyo has been reduced to ashes.” Clearly time had run out for Hirohito and Japan’s senior leadership, though the Japanese cabinet still had not asked the emperor to intervene to change the direction of the war, now plainly lost. It was left to the emperor’s new prime minister, 77-year-old Adm. Kantarō Suzuki (in office from April 7 to August 17, 1945), and new foreign minister Shigenori Tōgō, the leading figure in the peace movement, to stop the war with Hirohito’s cooperation, but not before August 1945.

![]()

Firebombing Tokyo, 1945

|  |

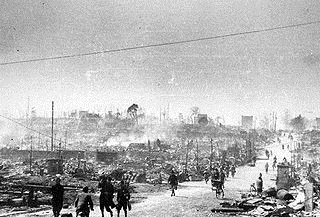

Left: Tokyo residents walk through a rubble-strewn neighborhood following the three-hour March 9 and 10, 1945, firebombing by 297 U.S. B‑29 four-engine Superfortresses loaded with napalm (jellied gasoline). Operation Meetinghouse (“Meetinghouse” being code for the urban area of the Japanese capital) was the single most destructive bombing raid in history: 100,000 people died; 25 percent of the city, 63 percent of its commercial area, and 18 percent of its industry were destroyed; and more than a million inhabitants made homeless. Tokyo was again firebombed on May 23 and 25, leaving three million out of 3.5 million residents (half the population in 1940) now homeless.

![]()

Right: Hirohito inspecting the ruins of Tokyo on March 18, 1945, following the previous week’s firebombing of his capital. The emperor had not been outside the imperial palace in five months, and the extent of Tokyo’s destruction struck him as more horrifying than that produced by the Great Tokyo Earthquake of 1923. The blast-and-burn campaign against Japan’s highly combustible cities, led by U.S. Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay of the XXI Bomber Command, a unit of the U.S. Twentieth Air Force, dramatically limited Japan’s options to avoid certain annihilation. In fact, an estimated four out of ten Japanese cities, containing lots of tightly packed, wooden structures, were destroyed in U.S. air attacks in 1944–1945.

|  |

Left: This aerial photograph shows what was left of one of Tokyo’s commercial and industrial districts (Chūō) along the Sumida River following the overnight March 9/10 firebombing. With the exception of some concrete buildings, the greater part of the district has been razed by U.S. bombers. The March firebombing has long been overshadowed by the August 6 and 9, 1945, U.S. atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which collectively killed and wounded an estimated 225,000 people. The August tally is conservative owing to the destruction and overwhelming chaos caused by the bombs, which made orderly counting impossible. The 1945 firebombing campaign, coupled with the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings, is thought to have killed more than one million Japanese civilians between March and the end of the war in August.

![]()

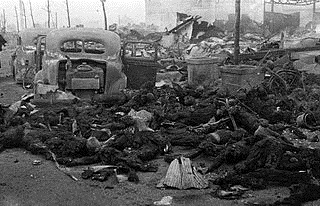

Right: The charred remains of civilians after the carnage and destruction wrought by 1,665 tons of bombs falling on Tokyo on the night of March 9/10, 1945. The majority of the bombs were 500-pound cluster bombs packed with napalm-carrying incendiary bomblets, which punched through thin roofing material or landed on the ground, throwing out a jet of flaming napalm globs. The city’s fire defenses were overwhelmed. Crew members in the last of the three bomber streams over Tokyo reported smelling the stench of charred human flesh. Ceasing any longer to be a viable target, the Japanese capital—over 50 percent destroyed by the end of May 1945—was spared further incendiary raids. One B‑29 flier quipped, “Tokyo just isn’t what it used to be.”

U.S. Army Air Forces Documentary on B-29 Raid on Tokyo Narrated by Future President Ronald Reagan

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click