YEAR-END RECORD DELIVERY OF B-29s

Washington, D.C. · December 31, 1943

By this date in 1943 Boeing delivered its 92nd B‑29 Superfortress to the U.S. government after the giant bomber began rolling off the assembly line the previous September. Even before the country was at war and government funds had been allocated, Boeing had produced a prototype of the long-range heavy bomber and had submitted it to the U.S. Army for evaluation. In all, Boeing built 2,766 B‑29s in Wichita, Kansas and Renton, Washington. The Bell Aircraft Co. built 668 in Georgia and the Glenn L. Martin Co. built 536 in Nebraska. Early plans to use B‑29s against Germany were scrapped when B‑17s and B‑24s were able to operate from neighboring Britain and Italy. Hence, Superfortresses were primarily used in the Pacific theater. As many as 1,000 B‑29s at a time bombed Tokyo in 1945, destroying large parts of the city. In March 1945 alone, more than 80,000 Japanese died in an incendiary raid on the city’s center—the highest loss of life of any aerial bombardment of the war. Finally, on August 6, 1945, a B‑29 named Enola Gay dropped America’s ultimate bomb, the world’s first atomic bomb, on Hiroshima. Three days later, on August 9, another B‑29, Bockscar, immolated Nagasaki in a second effort to bring an end to the war. On August 14, the last day of combat in World War II, B‑29s laid waste to the Japanese naval arsenal at Hikari on the southern tip of Japan’s main island, Honshū. The next day, August 15, 1945, Emperor Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa) spoke to his nation by radio, acknowledging the B‑29’s pivotal role when, in the understatement of the decade, he correctly reasoned that “the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage.” His country’s war in China and the Pacific theater had brought his “good and loyal subjects” to the edge of extinction: “To continue to fight . . . would not only result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese race, but also the destruction of all human civilization.” In lives alone, the tally of Japanese killed or missing is estimated at 1,740,000, with 94,000 military wounded and 41,000 prisoners of war; 393,400 civilians were killed and 275,000 were wounded or missing. By comparison, 108,504 Americans who served in the Pacific were killed, and 248,316 were wounded or listed as missing.

The large-scale Normandy invasion surprised the Germans. “When they [the Allies] have established bridgeheads in the Normandy and Brittany peninsulas and have sized up their prospects,” Hitler predicted with assurance to Japanese ambassador Baron Hiroshi Ōshima on May 27, 1944, at his Bavarian residence, “they will then come forward with an all-out second front across the Straits of Dover.” (For his part, Rommel stopped believing in a second Allied front.) For nearly seven weeks, the Allies’ ruse de guerre led Hitler to delay sending reinforcements from the Pas-de-Calais region to Normandy. On July 1, Hitler’s chief of staff on the OKW, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, telephoned Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, Commander-in-Chief West, frantically seeking advice on what to do next. Rundstedt did not mince words: “The writing [is] on the wall, make peace you fools.” Rundstedt was relieved of his command within the month, his sage advice ignored for nearly a year.

![]()

Operation Fortitude: Western Allies’ Strategic Deception Warfare, January–August 1944

|  |

Left: A dummy remains of Japanese civilians after the carnage and destruction wrought by Operation Meetinghouse, the March 9–10, 1945, firebombing of Tokyo. Toward the end of May, Tokyo was devastated two more times, leaving three million residents homeless.

![]()

Right: A virtually destroyed Tokyo residential section. Over 50 percent of Japan’s capital was reduced to ashes by the end of World War II. After one bombing run, one B‑29 flier quipped, “Tokyo just isn’t what it used to be.”

|  |

Left: Boeing built 3,970 of these four-engine, propeller-driven B-29 Superfortresses between 1943 and 1946. “Silverplate” B‑29s—Superfortresses specially modified for atomic bombing missions—carried out the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, respectively.

![]()

Right: Tokyo burns under a B‑29 firebomb assault, May 26, 1945. B-29 raids on Tokyo began on November 17, 1944, and lasted until August 15, 1945, the day Japan capitulated. Additional attacks on Tokyo were carried out by twin-engine bombers and fighter-bombers.

|  |

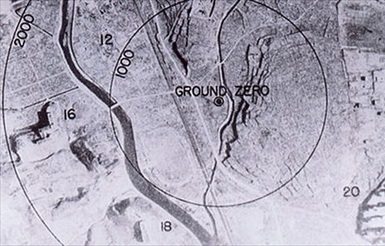

Left: Hiroshima, Japan, after the atomic bombing of August 6, 1945. Area around ground zero in 1,000‑ft circles. The bomb detonated in the air and the blast was directed more downward than sideways. Some 70,000–80,000 people, or roughly 30 percent of the population of Hiroshima, were killed by the blast and resultant firestorm, and another 70,000 injured. It is estimated that 4.7 sq. miles (12 sq. km) of the city were destroyed. In terms of buildings, 69 percent were destroyed and another 6–7 percent damaged.

![]()

Right: Nagasaki, Japan, after the atomic bombing of August 9, 1945. Area around ground zero (the city’s industrial valley) in 1,000‑ft circles. The bomb detonated 1,539 ft (469m) above ground, the explosion directed more downward than sideways. It generated heat estimated at 7,050°F (3,900°C) and winds that were estimated at 624 mph (1,005 km/h). Casualty estimates for immediate deaths range from 40,000 to 75,000. Total deaths by the end of 1945 may have reached 80,000.

Inside a Boeing B-29 Superfortress Aircraft Factory

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click