WAKE’S U.S. DEFENDERS SURRENDER TO JAPANESE

Wake Island, Western Pacific Ocean • December 23, 1941

On this date in 1941 Wake Island defenders surrendered after two attack waves of 1,000 Japanese marines each stormed the beaches. Two days earlier, in their largest attack yet on Wake Island, the Japanese had sent 49 aircraft, dive bombers and fighters both, to knock out the last of the island’s eight aircraft—this after launching their first air assault (36 bombers) on December 8, five hours after their fiery ambush of the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. (Wake was on the opposite side of the International Date Line.) Three days later, on December 11, 450 Japanese marines attempted their first landing. They were repulsed by U.S. Marine Corps shore batteries consisting of a half-dozen 5‑in guns from a World War I-era battleship as well as aggressive pilots flying Grumman F4F Wildcats, who shot down 24 enemy aircraft. Two Japanese destroyers were sunk—the first Japanese warships lost in World War II—and many more vessels damaged.

Wake Island, an American Pacific outpost between Hawaii and Guam, had been identified as a “priority defense requirement” four months before August 1941, the month building the island’s defenses began. By December the three coral islets had become the most heavily defended U.S. atoll in the Western Pacific but with a significant weakness: no radar to alert its defenders to approaching enemy aircraft.

A week after the deadly Japanese assaults on Pearl Harbor and Wake Island, two U.S. task forces (TF 11 and TF 14) steamed toward Wake from Hawaii. Among the warships were the fleet carrier Saratoga with 66 aircraft of her air group and a dozen largely obsolete Brewster F2A Buffalo fighters for the Marine Wake squadron, 3 heavy cruisers, 10 destroyers, and elements of the 4th Marine Defense Battalion. The relief expedition was still 425 miles away when Japanese marines successfully assaulted the island on a gusty, rainy December 23. After eleven hours of fierce resistance, the enemy, which outnumbered Wake’s defenders three or four to one, captured roughly 500 Marines, Navy personnel, and soldiers and 1,150 civilian-contractor volunteers, the majority beginning 3‑1/2 years of captivity as slave laborers in China and Japan. Only about two‑thirds of the men survived their captivity. Bedeviled by heavy seas Adm. Frank Fletcher’s relief force, striving to arrive on December 24 in the vicinity of now-fallen Wake, was instead recalled to Pearl Harbor. The size and composition of the relief force was later recognized as incapable of lifting the enemy siege or evacuating the island in the two weeks prior to Wake’s capture or dislodging the invaders in the days afterward.

The POWs who remained on the island were employed by the Japanese in building island defenses: concrete and coral block houses and pillboxes with interlocking fire, tank traps, land mines, and barbed-wire entanglements along the shoreline, aircraft revetments at the airfield, and the like. In September 1942 a second batch of POWs was transported to prison camps in China. The 98 heavy equipment operators who remained were executed in early October 1943 when the Japanese garrison feared an imminent invasion from a U.S. armada that included the carrier USS Yorktown and many cruisers and destroyers.

The enemy garrison, numbering 4,400 army and navy personnel at its height, remained entrenched on Wake Island through September 4, 1945, surrendering to a detachment of U.S. Marines two days after their nation’s formal surrender in Tokyo Bay. Japanese Rear Admiral Shigematsu Sakaibara, who ordered the execution of the 98 captive civilian workers, was hanged on June 18, 1947, as a war criminal.

![]()

Battle of Wake Island, December 8–23, 1941

|

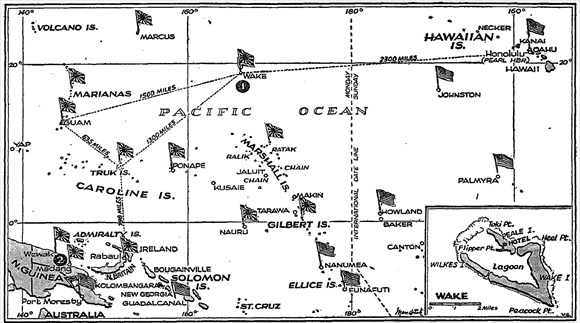

Above: Map of the Western Pacific Ocean, circa early 1943. Japanese-occupied Wake Island atoll (Wake Island, Wilkes Island, and Peale Island) is located in the center of the map above the black circle enclosing a “1.” Prior to its capture, the U.S. Navy-Marine garrison on Wake had been an important intelligence gathering center and warning outpost. Wake had also been a stopover for Pam Am’s big China Clipper flying boats. To the east of Wake Island the Pacific outposts are in American hands. Japanese island strongholds lie to the west of Wake and much of the south; e.g., the Marianas, Guam, and the Marshall and Gilbert islands, which the Americans took during campaigns that lasted from November 1943 through August 1944.

|  |

Left: Columns of smoke rise from on either side of Wake Island’s airstrip after a Japanese air attack in December 1941. The Japanese lost 7 aircraft, 2 destroyers, 2 transports, 2 patrol boats, and over 1,100 men, with many more wounded, in the Battle of Wake Island. U.S. dead were 122 (including civilian contractors), with 49 wounded and 2 missing. Interned were 1,104 civilians, of whom 180 died in captivity. Wake’s heroic defense and sacrifice were the chief bright spots in the grim first months of the Pacific War.

![]()

Right: Just hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, 36 Japanese medium bombers flown from bases on the nearby Marshall Islands attacked Wake Island, destroying 8 of the 12 F4F‑3 Wildcat fighter aircraft belonging to Marine Corps fighter squadron VMF‑211 on the ground. This photo, taken after the Japanese had captured the island, shows the wreckage of Wildcat 211‑F‑11, flown by executive officer Capt. Henry T. Elrod on the morning of December 11, 1941, in the attack that sank the destroyer Kisaragi with the loss of all 167 hands. Elrod was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor—the first aviator to receive the medal in World War II—for his actions on Wake during the second Japanese landing attempt on December 23. At the end of that day, however, the island’s defenders were left with no serviceable aircraft to turn back the invaders.

|  |

Above: Japanese Patrol Boat No. 32 and Patrol Boat No. 33 were two ex-destroyers reconfigured in 1941 to launch a landing craft carrying 250 naval infantrymen over a stern ramp. In the photo on the left the two patrol boats (Patrol Boat No. 32 on the left) have been run aground on the south coral shore of Wake Island near the airstrip before dawn on December 23, 1941. Island defenders, with a 3‑in gun, managed to draw a bead on beached Patrol Boat No. 33, less than 500 yards from their position. Some of their 15 projectiles touched off the ship’s magazine, and the warship began to burn. (Her remains are shown in the right photo.) The illumination provided by the burning ship revealed her sister ship, Patrol Boat No. 32, which was hit with 5‑in, 50 lb shells from coastal artillery guns. Twenty-five minutes later that boat too was completely demolished. The Japanese marines, however, were able to slip over the patrol boats’ sides in the darkness and sprint across the coral reef for cover.

Radio Broadcast Announcing Fall of Wake Island to Japanese

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click