U.S. ARMY ACTIVATES SECRET INTELLIGENCE SCHOOL

Camp Ritchie, Maryland • June 19, 1942

On this date in 1942 the U.S. Army activated the Military Intelligence Training Center (MITC) at Camp Ritchie. Former property of a failed ice company, the rural site was converted into a summer training camp for the Maryland National Guard in 1926. Sixteen years later the U.S. Army replaced canvas tents with permanent buildings. Camp Ritchie’s secluded location 70 miles north of the nation’s capital seemed ideal for the new task at hand: the first-of-its-kind training center for centralized military intelligence and psychological warfare.

The Ritchie Boys, as camp graduates were soon called, were U.S. special military intelligence officers and enlisted men who were embedded in regular army units. The soldiers were tasked with collecting military intelligence in the field and providing clear and speedy reports up the chain of command. Between 15,200 and 19,000 servicemen (sources vary) were trained at the top-secret facility, re-christened Fort Ritchie after the war. The students were rigorously trained in methods of intelligence, counterintelligence, interrogation of prisoners of war, investigation, aerial photography analysis, terrain intelligence, and psychological warfare. Most students were direct descendants of immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe. Roughly 14 percent of them were German and Austrian Jews who had fled Nazi tyranny and persecution. Settling in the United States as “noncitizen residents” (after December 11, 1941, many were reclassified as “enemy aliens”), these exiles volunteered or were drafted into the U.S. Army. When their fluency in foreign languages, especially German, French, and Italian, was discovered by their commanders or in Army personnel files—and equally important when their innate familiarity with the culture, psyche, and behavior of America’s enemies was recognized as a valuable tactical asset to use in the war effort—these soldiers were whisked to Camp Ritchie.

For eight intense weeks, a period often prolonged by highly specialized courses, MITC students practiced mock interviews, interrogations, and intelligence gathering. In all, there were 31 eight-week sessions, the first ending in September 1942. Captured German and Italian soldiers from the failed Axis North African Campaign provided students at Camp Ritchie with guinea pigs to try out their new or enhanced skill sets.

Starting with the June 1944 D-Day landings in Northwest France, Camp Ritchie graduates saw combat attached to fabled units such as the U.S. 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions and other frontline armored and infantry divisions and regiments. Immediately teams of German-language POW interrogators and French-speaking military intelligence interpreters began grilling captured combatants, members of the French Resistance, and local residents to glean actionable, tactical information about the enemy’s fighting capabilities, morale, troop size, location and movements, local defenses, minefields, booby traps, machine gun nests, and command posts that contributed to the Allies’ early battlefield successes. As U.S. forces cut across France and into Germany, Ritchie Boys mostly stayed with their assigned units and focused on collecting strategic-level intelligence concerning German railroad, military-industrial, scientific, chemical, weapons, and petroleum complexes, to name a few targets of interest to senior Allied commanders and war planners.

Ritchie Boys took part in every major North African and European engagement and campaign. A few saw service in the Pacific. Reportedly 60 percent of the credible U.S. intelligence gathered in Europe came from Ritchie Boy operatives. After European hostilities ended in May 1945 Ritchie Boys continued to provide vital intelligence as part of the Army’s de-Nazification efforts. During this period many servicemen of Jewish extraction visited their ancestral homes. Sadly, some fates of missing family members and friends remained forever unknown, whereas other missing persons were reported to have died in Allied aerial or artillery bombardments or by starvation, physical abuse, torture, exhaustion from slave labor or forced marches, disease, execution, or gassing in death chambers.

![]()

![]()

U.S. Army’s Wartime Military Intelligence Training Center at Camp Ritchie, Maryland

|  |

Left: In 1942 the U.S. War Department took possession of Camp Ritchie, named after a Maryland governor. A summer training base for the state’s National Guard, the War Department repurposed the leased site as a U.S. Army training center for combat intelligence. Officially the camp was known as the Military Intelligence Training Center, or MITC. MITC graduates would become known as the “Ritchie Boys”: the base’s wrought-iron front gate still proudly bore the name “Camp Ritchie.” In this photo, students are seen engaged in a coding exercise in MITC’s Signal Intelligence Code Room.

![]()

Right: Demonstrations of how to properly capture, handle, and “non-forcefully” interrogate prisoners were part of MITC’s intensive eight-week intelligence training sessions, 31 all totaled. Demonstrations like the one in the photograph allowed soldiers to see firsthand how their classroom instruction was to be used in combat zones. For the sake of authenticity the “prisoner” in the middle is an American serviceman dressed in a German uniform playing the part of a German POW. Jewish soldiers found it galling to wear a German uniform for any reason. Other enemy props included pistols, rifles, mortars, hand grenades, machine guns, and field artillery.

|  |

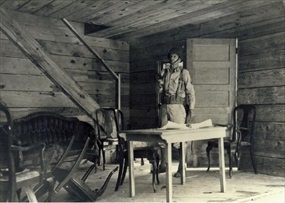

Above: Soldiers sit on hillside bleachers watching actors raid a cutaway farmhouse and conduct maneuvers in confined spaces, searching for both enemy combatants as well as actionable intelligence like maps, documents, and codebooks, radio transmitters and receivers hidden in the nooks, crannies, walls, and beneath floorboards of the house.

2016 American Heroes Channel’s Interview with Guy (Günther) Stern, Former Ritchie Boy

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click