JAPAN MOVES TO STRENGTHEN IWO JIMA GARRISON

Chidori Airstrip, Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands • June 19, 1944

On this date in 1944 Japanese Lt. Gen. Tadamichi Kuribayashi stepped from his plane onto the dirt runway of Iwo Jima’s Chidori airstrip, or Airfield No. 1. Iwo Jima, roughly 8 square miles of mostly black volcanic ash and stone (cinder) anchored by 554‑ft‑high Mt. Suribachi, had been a Japanese possession since 1891. For much of its recorded history the island’s worth to the Japanese Empire lay in a sulfur quarry and refinery, which employed a small civilian workforce. Even before mid‑1944, when U.S. soldiers, sailors, Marines, and airmen polished off the 40,000-strong Japanese military garrisons on Saipan and Tinian islands (see map below for location), Tokyo realized the strategic importance of Sulfur Island (Iō Tō), as Iwo was also called, to defending the homeland. Troops and supplies began pouring into Iwo Jima, chiefly from the Imperial Japanese Army’s 109th Division, since 1937 a veteran of the Sino-Japanese conflict.

Americans too grasped the importance of Iwo Jima that same summer and fall. Seizing enemy bases in air, sea, and ground operations in an island-hopping drive northward, U.S. military brass appreciated Iwo’s potential as a fighter escort base and an emergency airfield for U.S. Army Air Forces’ Twentieth Air Force B‑29 Superfortress heavy bombers that would soon be making bombing runs over mainland Japanese cities, armament and aircraft factories, and army and naval airfields and yards. The warlords in Tokyo tasked Kuribayashi with making any Allied attempt to seize the island as painful as possible.

Summoned to the office of Prime Minister, War Minister, and firebrand Gen. Hideki Tōjō in late May 1944, followed by an audience with Shōwa Emperor Hirohito, Kuribayashi (1891–1945) dutifully accepted the no-return nature of the mission for himself and upwards of 21,000 army and naval personnel assigned to the island’s defense. Earlier in his career Captain Kuribayashi spent 2 years in Washington, D.C., as a military attaché and thus saw American military and industry up close. Kuribayashi brought his experience and perspective to the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff in Tokyo between 1933 and 1937. Under no illusions about American prowess, he confided repeatedly to his family, “America is the last country in the world Japan should fight.”

Kuribayashi’s appreciation of the mettle of his country’s enemy must certainly have grown after he absorbed the lessons learned from the shellacking Americans inflicted on Japan’s military on Saipan (June 15 to July 9, 1944) and Tinian (July 24 to August 1, 1944). Fighting on the beach’s edge or launching waves of unsuccessful Banzai charges with weapons that included, absurdly, swords, sticks, and stones were scraped from his playbook. No, his strategy consisted of a prolonged defense of the island based on building an elaborate system of fortified caves and subterranean passageways and chambers, some capable of holding 300–400 men. The idea was to minimize the effects of U.S. aerial and naval bombardment and, secondly and more importantly, connect myriad Japanese reinforced concrete blockhouses, pillboxes, and openings from which small-to-large caliber artillery, mortar, and rocket fire could thwart or kill as many encroaching enemy men and pieces of armor as possible. By the time U.S. Marines landed on Iwo Jima on February 19, 1945, more than 11 miles of Kuribayashi’s projected 17 miles of passageways connecting defensive strongholds had been completed.

Kuribayashi planned a campaign of attrition in the hope that it would delay U.S. bombing of Japanese urban and industrial centers or, better yet, impel President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration to reconsider invading his homeland if American casualties on Iwo Jima were sufficiently high to entice Japan’s enemies to the negotiation table and quickly make peace. Kuribayashi’s campaign was a stubborn and costly one for Iwo’s invaders and defenders. Japanese troops under their ingenious and courageous commander were responsible for the deaths of between 6,102 and 6,821 Marines (sources vary), a third of all Marines killed during the entire four‑year Pacific conflict. The U.S. Navy lost 719 men, the Army 41 killed or missing. Total U.S. casualties amounted to a quarter of the 110,000 servicemembers who took part in the Battle of Iwo Jima. Twenty-seven Medals of Honor were awarded to Marines and sailors, many posthumously, more than were awarded for any other single operation during the war.

![]()

Iwo Jima: Japanese Citadel Protecting the Homeland

|

Above: Location of the pork-chop-shaped island of Iwo Jima in relation to Tokyo (760 miles due north) and the Mariana Islands (Saipan, 730 miles to the southeast). Iwo Jima was a Japanese citadel protecting the homeland. Iwo Jima had two completed airstrips with a third under construction when the U.S. launched Operation Detachment, the invasion of Iwo Jima. American intelligence reported that there were 13,000 Japanese defenders on the island, when in fact there were between 21,000 and 23,000 well-trained, well-disciplined, and initially well-provisioned men from Army and Navy units. Iwo Jima-based Japanese aircraft were able to bomb U.S. B‑29 bases in the Marianas, and radio operators on Iwo Jima were able to send advance warning to the Japanese Home Islands every time flotillas of the long-range Superfortresses passed north overhead. An early-warning radar station was also able to garner advance notice of U.S. air strikes directed at Iwo Jima itself.

|  |

Left: Just weeks after Lt. Gen. Tadamichi Kuribayashi’s arrival, American air and naval bombardment had demolished all 80 Japanese fighter aircraft parked on Iwo Jima’s airstrips, along with every single building. In this photo Kuribayashi (center) looks over a blueprint of deep underground defenses drawn up by mining engineers. By the time U.S. Marines hit the shores of Iwo Jima on February 19, 1944, Kuribayashi’s garrison men had managed to honeycomb the island with more than 11 miles of tunnels and 5,000 caves, build reinforced concrete blockhouses and mutually supporting hidden pillboxes, bunkers, and other fortifications, and emplace immobilized armored tanks, dug in and camouflaged, in the broken terrain. Iwo Jima had been converted into an impregnable fortress it seemed, virtually immune to naval and air bombardment.

![]()

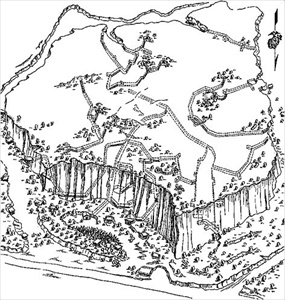

Right: Sketch of Hill 362A on Iwo Jima’s northwest coast looking at top and 80‑ft-tall north face. Hill 362A had four separate underground tunnel systems (represented by dotted lines); one system reached over 1,000 ft in length and had 7 different entrances and exits. Inside the hill were command posts, hospitals, and ammunition dumps—all intolerably hot, stuffy, and humid as Kuribayashi characterized the island’s subterranean conditions. This sketch is one of five prepared by the 31st U.S. Naval Construction Battalion.

|  |

Left: In this painting by an unknown Japanese artist, enemy soldiers take cover behind a wrecked American plane and fire down on Marine riflemen and amtracs as they slog their way from a landing beach up slopes of soft volcanic ash seemingly unswayed by incoming heavy mortar and artillery shells and spouting fireballs of buried mines. In 36 days of hellish fighting approximately 28,000 combatants on both sides died. American survivors exceeded 103,000 out of the 110,000 men from all service branches who engaged Iwo’s defenders. On the Japanese side, only 1,083 of the 22,786 stalwart defenders survived to be taken captive during the cataclysmic island struggle, which officially ended on March 26, 1945, when Iwo Jima was declared secure. Be that as it may, enough defenders (one source says as many as 3,000) managed to slip into hiding, possibly inspired by their fearless commander-in-chief to “continue to harass the enemy with guerrilla tactics even if only one of us remains alive.” Over the next 3 months 1,602 determined Japanese resisters were killed in small unit clashes by soldiers of the U.S. Army garrison force.![]()

Right: In this painting by artist Chesley Bonestell, from high atop Mt. Suribachi Landing Ships, Tank (LSTs) and transports are visible on the invasion beaches that were assigned to the U.S. Fifth Marine (closest in foreground) and Fourth Marine Divisions. Today, a pristine white monument dedicated to the Fifth Marines sits on the forward edge of Mt. Suribachi’s peak, facing the landing beaches below. It was from among the Fifth Marine ranks that six men were selected on the afternoon of February 23 to climb the extinct volcano for the second time and raise the flag made famous in Joe Rosenthal’s Pulitzer Prize-winning image. Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, an on-shore eyewitness, remarked that Rosenthal’s widely renown black-and-white flag-raising photograph (possibly the most reproduced photograph of all time) would ensure the existence of the U.S. Marine Corps for the next 500 years. Returned to Japanese jurisdiction in 1968, the island welcomes civilian visitors once a year.

U.S. Government Office of War Information 1945 Color Documentary “To the Shores of Iwo Jima”

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click