STRIKE INTO NAZI HEARTLAND TO GO THROUGH AACHEN

SHAEF HQ, Versailles, France • September 5, 1944

On this date in 1944 Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, determined that the route U.S. forces would take from liberated areas in France and Belgium eastward into Nazi Germany would pass through the ancient city of Aachen, once the seat of government of Charlemagne’s Holy Roman Empire. From Aachen, which bisected Germany’s defensive West Wall (Siegfried Line) consisting of pillboxes, forts, bunkers, minefields, and antitank obstacles, Allied armies would have a clear shot at capturing the Ruhr Basin, an industrial region of huge economic, political, and psychological importance to Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich. The end of the war in Europe would surely follow an Allied victory in the Ruhr.

Fighting around Aachen began within days of Eisenhower’s decision. An attempt to save the picturesque city of 160,000 inhabitants by declaring it an “open city” (similar to what occurred in Paris two weeks before) fell through when Hitler relieved the city’s divisional commander, who had all of 600 men and 12 tanks at his disposal, and replaced him with Oberst (Colonel) Gerhard Wilck, commander of the 246th Volksgrenadier Infantry Division. Despite many men in Wilck’s division having less than 10 days infantry training, they proved to be exceedingly ferocious adversaries. Additional German reinforcements took up positions north and south of the city, followed by combat units moving into the mostly evacuated city itself, making 12,000 defenders in all.

When the American offensive began in earnest on October 2, 1944, the attackers (Maj. Gen. Leland Hobbs’ 30th Infantry Division and Maj. Gen. Clarence Huebner’s 1st Infantry Division, both part of Gen. Courtney Hodges’ U.S. First Army) were slowed by savage house-to-house firefights and grenade duels on the city’s outskirts despite the U.S. Ninth Air Force bombing and strafing enemy positions augmented by divisional heavy artillery at point-blank range. On October 11, after Wilck ignored the U.S. ultimatum to surrender his garrison, the Americans hit Aachen with intense heavy artillery and aerial bombardment. Five days later the two attacking U.S. divisions linked up to overwhelm the city’s nearly 4,400 well-entrenched defenders (over a hundred were police officers), who were supported by five tanks, nearly 50 assault guns, and one 20mm antiaircraft gun.

Cautiously American infantrymen, tanks and other armored vehicles, 155mm (6.1 in) “Long Tom” field guns, Browning M1919 machine guns, bazookas, flamethrowers, and other deadly hardware advanced into the city, shelling and firing into buildings and cellars ahead of them to clear or snuff out defenders. Because of a breakdown in internal communications, Wilck knew the location of only about 500 of his fighting men. By nightfall, as American troops methodically swept through the ruined city, some 1,600 more enemy soldiers were captured, which ended the Battle of Aachen.

Unfortunately for the Western Allies the six–week battle for Aachen threw a monkey wrench into their timetable to capture the Ruhr industrial complex and so cripple the enemy’s war-making capability. And before that could happen there was the pesky matter of wresting control of a series of Roer River dams behind the Huertgen Forest, a short distance southwest of Aachen, that stood in their way to a Rhine River crossing. At six months, the Battle of the Huertgen Forest would prove to be the longest single battle the U.S. Army ever fought.

![]()

Battle of Aachen: Urbanized Meat Grinder for U.S. and German Armies

|

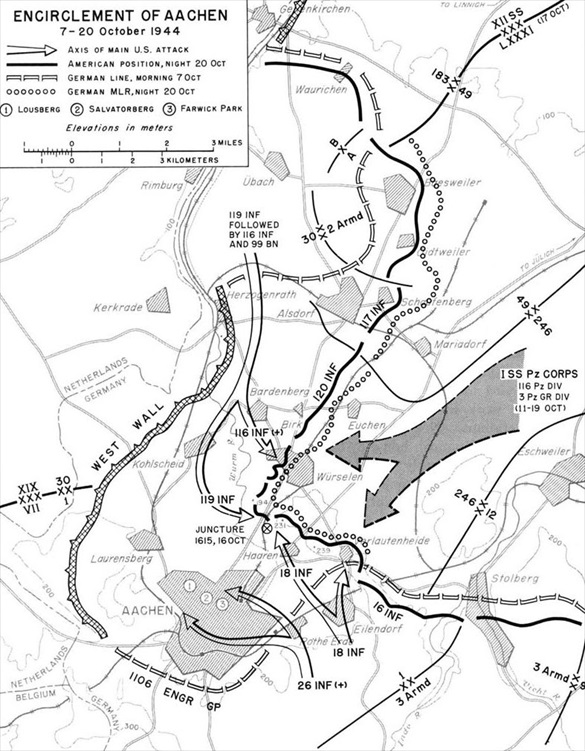

Above: Map of U.S. encirclement of Aachen, the first important city on German soil to fall to the advancing Allies, who launched attacks from multiple directions (see arrows). Eighty percent of the city was destroyed by aerial and field bombardment when the Battle of Aachen (October 2–21, 1944) ended. Americans and Germans each suffered 5,000 casualties. The U.S. took over 11,600 German prisoners, including nearly 3,500 captured within the city. Aachen was one of the largest urban battles fought by U.S. forces in World War II. Though the battle ended in the city’s capitulation, the Germans’ tenacious defense significantly disrupted Allied plans to advance into Germany.

|  |

Left: The commander of an M4 Sherman tank looks through binoculars from his turret hatch on the day before the city of Aachen fell. The tanks mounted an extra .50 caliber machine gun in front of the turret, useful in street fighting for suppressing fire from upper-story windows. In the distance is an M10 tank destroyer, a lightly armored vehicle sporting a 3‑in gun and a fully rotating, open-topped turret specifically designed to take out enemy tanks. In one two-day period (October 9–10) the 30th Infantry Division claimed 20 German tanks: 12 destroyed by 105mm howitzers, 5 by supporting tanks and tank destroyers, and 3 by bazookas.

![]()

Right: American artillerymen fire a powerful M12 155mm (6.1 in) self-propelled gun at a target in the streets of Aachen in October 1944. These weapons were used to clear out German bunkers when tank fire proved ineffective. With bitter experience as a teacher, GIs assumed every building, cellar, air-raid shelter, and sewer was occupied by hostile forces. Light artillery and mortar fire thus swept enemy streets ahead of advancing infantrymen, who made proactive use of demolition charges, flamethrowers handled by two-man teams, bazookas, and grenades. The Battle for Aachen was remembered by one person as a fight “from attic to attic and sewer to sewer.”

|  |

Left: Col. Gerhard Wilck (sitting in front passenger seat, head bowed) and his headquarters group after their surrender. On the afternoon of October 19, 1944, Wilck, who commanded the 246th Volksgrenadier Infantry Division, which had taken responsibility for this sector of the Siegfried Line, issued a written order of the day: “The defenders of Aachen will prepare for their last battle. Constricted to the smallest possible space, we shall fight to the last man, the last shell, the last bullet, in accordance with the Fuehrer’s orders. . . . I expect each and every defender of the venerable Imperial City of Aachen to do his duty to the end, in fulfillment of our Oath to the Flag. . . . Long live the Fuehrer and our beloved Fatherland!” Fanatical exhortations like this one did little to forestall the city’s tragic end. On October 19 and 20 resistance swiftly collapsed inside and outside Aachen. Their bags already packed and ready to go, Col. Wilck and his staff surrendered to the Americans on October 21, 1944.

![]()

Right: The endless procession of German prisoners captured in the fall of Aachen march through ruined streets into captivity. Civilians who witnessed their homes reduced to rubble by advancing Americans and well-entrenched German defenders heaped abuse on their exhausted countrymen as they passed by, causing American soldiers to occasionally separate the two groups. “The city is as dead as a Roman ruin,” wrote a U.S. observer, “but unlike a ruin it has none of the grace of gradual decay. . . . Burst sewers, broken gas mains and dead animals have raised an almost overpowering smell in many parts of the city. The streets are paved with shattered glass; telephone, electric light and trolley cables are dangling and netted together everywhere, and in many places wrecked cars, trucks, armored vehicles and guns litter the streets.”

Contemporary Newsreel Account of Battle for Aachen, October 1944

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click