PURSUE ATOMIC RESEARCH—EINSTEIN TO ROOSEVELT

Peconic, Long Island, New York · August 2, 1939

On this date in 1939, one month before the outbreak of World War II, German-born mathematician and physicist Albert Einstein wrote President Franklin D. Roosevelt about the possibility of using a nuclear chain reaction to produce enormous amounts of energy that could be used in making a bomb. German scientists, he noted in closing his letter, were busy researching just that possibility. Roosevelt did not receive Einstein’s confidential hand-delivered letter until October 11, but when he did he acted on it quickly, appointing a committee, the S‑1 Uranium Committee, to direct the research starting with a $6,000 outlay.

In 1942 Italian-born Enrico Fermi and Hungarian-born Leó Szilárd—colleagues whom Einstein had mentioned in his letter—went on to create the first atomic chain reaction at the University of Chicago and became members of the Manhattan Engineering District, the cover name for America’s atomic bomb program that evolved out of the S‑1 Committee. Leading the scientific side of the project was a young 38‑year-old American, J. Robert Oppenheimer. Commanding the project overall was West Point graduate Brig. Gen. Leslie Groves.

Apart from the initial July 16, 1945, detonation of a nuclear (plutonium) bomb nicknamed “Gadget” at the top of a 100‑ft tower in the New Mexico desert, Manhattan’s deployable nuclear weapons were “Little Boy” (uranium bomb) and “Fat Man” (plutonium bomb). (Szilárd and 154 nuclear scientists lost the moral argument to invite Japanese observers to view a second nuclear detonation, which they believed would have induced Japan’s leaders to surrender unconditionally and thus spare lives.)

Initially six Japanese cities were identified as candidates for nuclear incineration, then four: Hiroshima on southern Honshū Island, Kokura (Hiroshima’s backup) and Nagasaki (Kokura’s backup) on Kyūshū, and Niigata on northern Honshū. Weather that permitted visual bombing settled Hiroshima’s terrible fate; clouds and smoke over Kokura from an earlier firebombing of Yawata (Yahata), less than 5 miles away, settled that of Nagasaki. On August 15, six days after Nagasaki and tens of thousands of deaths later, Japan announced its unconditional surrender to the Allies, signing the Instrument of Surrender on September 2, 1945, officially ending World War II.

![]()

Trinity Site, New Mexico, 1945: Detonating the First Nuclear Bomb

|  |

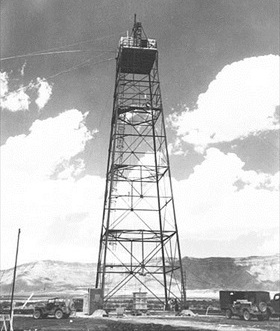

Left: The 100-ft-tall tower constructed for the Trinity test. Trinity was the codename of the first detonation of a nuclear device, which occurred at the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range (now part of the White Sands Missile Range) in Southern New Mexico on July 16, 1945, a date usually considered to be the beginning of the Atomic Age.

![]()

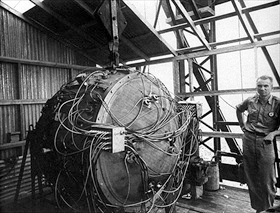

Right: The explosives of the “Gadget” were raised up to the top of the tower for the final assembly in mid-July 1945.

|  |

Left: Norris Bradbury, bomb assembly group leader, stands next to the partially assembled “Gadget” atop the test tower, July 15, 1945.

![]()

Right: Trinity was a test of an implosion-design plutonium device, the same conceptual design used in the second nuclear device dropped on Japan, “Fat Man,” which was detonated over Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9, 1945. This photo was taken 0.016 of a second after test detonation.

|  |

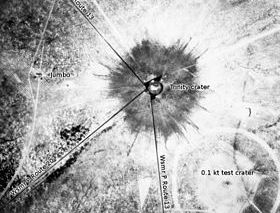

Left: An aerial photograph of the Trinity crater shortly after the test. The nuclear device exploded with an energy equivalent to around 20 kilotons of TNT and left a crater of radioactive glass 10 ft deep and 1,100 ft wide. The shock wave was felt over 100 miles away, and the mushroom cloud reached 7.5 miles in height.

![]()

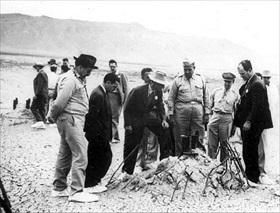

Right: J. Robert Oppenheimer (center, in light-colored hat), Gen. Leslie Groves (to Oppenheimer’s left), and others at ground zero of the Trinity test site sometime after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

University of California Television: The Manhattan Project

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click