PACIFIST BECOMES JAPAN PRIME MINISTER

Tokyo, Japan · October 9, 1945

On this date in 1945 in Tokyo, Baron Kijuro Shidehara became Prime Minister of Japan at the head of a constitutional government committed to pursuing a peaceful future. Before the war Shidehara had been a prominent Japanese diplomat and a leading proponent of pacifism in Japan. On October 9 the American occupation authorities repealed the May 1925 Peace Preservation Law, which had given the Imperial Japanese government and its Thought Police within the Home Ministry carte blanche to outlaw any form of political and religious dissent, as well as arrest over 70,000 people between 1925 and 1945. The American authorities also removed from their posts about 200,000 persons who were deemed responsible for leading the war effort. The 1946–1948 International Military Tribunal for the Far East, or Tokyo Trials—equivalent to the Nuremberg Trials in postwar Germany—sentenced sixteen former ministers, generals, and ambassadors in Japan’s military-dominated government to imprisonment. Seven former military and political leaders were sentenced to death, chief among them wartime prime minister Hideki Tōjō, who was hanged in 1948 along with his foreign minister and war minister. Japanese Emperor Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa) and all members of the Imperial family, such as Prince Yasuhiko Asaka who was implicated in the 1937 Nanking massacre in China’s capital city, were not prosecuted for involvement in any war crimes—both the Truman administration and Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers in Japan, gave Hirohito a free lifetime “Get Out of Jail” card, believing that occupation reforms would be implemented more smoothly if, instead of deposing and prosecuting the emperor, they used him to legitimize their changes. American and Japanese leaders moved almost as one to whitewash Hirohito’s wartime role to justify keeping him on his throne—this had been the chief sticking point in moving Japan to accept unconditional surrender. By colluding, the Japanese and U.S. occupation regime contributed to the memory loss of the Japanese people for the horrific role their country played in the first half of the 20th century, a memory loss that the sons and daughters of Japan’s neighbors must deal with as that country moves to claim a leadership role in Asia and the Pacific.

![]()

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”1905246358,082481925X,0826415210,0870119796,0062287931,0060931302,1585678910,0393320278,0674033396,0815411715″ /]

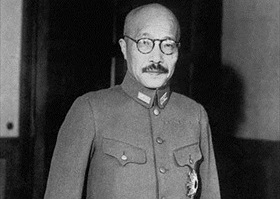

Gen. Hideki Tōjō and His Emperor

|  |

Left: Defendants at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (1946–1948). Gen. Hideki Tōjō (1884–1948), former war minister and prime minister of Japan, is fifth from left in first row of the defendants’ dock. Alluding to Emperor Hirohito’s success in dodging indictment as a war criminal, Judge Henri Bernard of France concluded that the war in the East “had a principal author who escaped all prosecution and of whom in any case the present Defendants could only be considered as accomplices.”

![]()

Right: Tōjō in military uniform. On July 22, 1940, Tōjō was appointed Army Minister. During most of the Pacific War, from October 17, 1941, to July 22, 1944, he served as Prime Minister of Japan. In that capacity he was directly responsible for the attack on Pearl Harbor. After the war Tōjō was arrested, sentenced to death for war crimes during the Tokyo Trials, and was hanged on December 23, 1948.

|  |

Left: Soldiers parading before Shōwa Emperor Hirohito, a revered symbol of divine status. While perpetuating a cult of religious emperor worship, Hirohito also burnished his image as a warrior in photos and newsreels riding Shirayuki (White Snow), his beautiful white stallion. One news agency reported that Hirohito made 344 appearances on Shirayuki.

![]()

Right: Shōwa Emperor Hirohito, seated in middle, as head of the Imperial General Headquarters in 1943. As part of the Supreme War Council, the Imperial General Headquarters coordinated wartime efforts between the Imperial Japanese Army and Imperial Japanese Navy. In terms of function, it was roughly equivalent to the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Contemporary Documentary on the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, 1946–1948

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click