NAZIS JAIL OUTSPOKEN PASTOR NIEMOELLER

Berlin, Germany · July 1, 1937

On this date in 1937 the Gestapo arrested outspoken Lutheran theologian and pastor Martin Niemoeller. The next year Niemoeller was tried for activities against the State. Released after the trial, Niemoeller was rearrested—presumably because Deputy Fuehrer Rudolf Hess decided to take “merciless action” against him when the court didn’t. Niemoeller spent the next eight years in Sachsenhausen and Dachau concentration camps as a “personal prisoner” of Adolf Hitler. Initially a supporter of the Hitler, Niemoeller became (like his colleague-in-faith, theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer) one of the founders of Germany’s Confessing Church (Bekennende Kirche), which arose in the 1930s in opposition to state-sponsored efforts to Nazify German churches and “dejudaize” Jesus and the New Testament. He opposed the Nazis’ Aryan Paragraph, which first appeared in the April 1933 Reich Civil Service Law but found its way into all sorts of public and ecclesiastical statutes that stigmatized and marginalized non-German Volk and Germans of Jewish descent. For instance, the Aryan Paragraph removed “non-Aryan” clergy from official church positions and rosters lest their theology undermine Christian faith and family life. The 1930s “Deutsche Christen” movement of clergy and lay people propagated anti-Semitic, voelkisch (chauvinist) ideas in German schools, on church councils, and in other social arenas. Few clerical or lay leaders departed from the Nazi Party line that a Jewish “problem” existed and that it required restrictions on the “excessive” influence of Jews. In this way the German church both reflected and contributed to the political, social, and racial milieu that made the Holocaust possible. Niemoeller is best known for penning the poem “First they came for…” (see below), an indictment of German intellectuals like himself for not doing enough to stop Hitler and the Nazis from liquidating their opponents from German society. (The substance and order of the groups mentioned in the poem vary from version to version, as Niemoeller formulated them differently depending on his audience.) Released from imprisonment in 1945 by the Allies, Niemoeller continued his career in Germany as a clergyman and as a leading voice of penance and reconciliation for the German people after World War II.

“First They Came . . .” by Martin Niemoeller

First they came for the socialists

And I didn’t speak out because I wasn’t a socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists

And I didn’t speak out because I wasn’t a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews

And I didn’t speak out because I wasn’t a Jew.

Then they came for me

And there was no one left to speak for me.

![]()

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”1590176812,158980063X,0802869025,0800629310,0807845604,1107663334,0275970450,0803221657,1573834173,0195053060″ /]

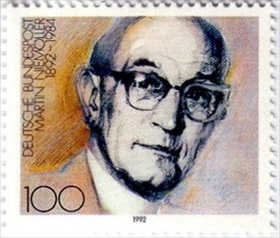

German Stamps Commemorating Theologians Martin Niemoeller and Dietrich Bonhoeffer

|  |

Left: Martin Niemoeller, 1892–1984. After his imprisonment Niemoeller often spoke of his deep regret about not having done enough to help the victims of the Nazis. In the 1950s he became a vocal pacifist and anti-war activist and a committed campaigner for nuclear disarmament. From 1961–1968 he served as President of the World Council of Churches. In 1966 he was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize.

![]()

Right: Dietrich Bonhoeffer, 1906–1945. Unlike Niemoeller, who was imprisoned from 1937 to 1945, Bonhoeffer was free to engage in anti-state activities while serving in the German Abwehr (Military Intelligence) under the protection of its chief, Adm. Wilhelm Canaris, right up to his imprisonment in April 1943. Both Canaris and Bonhoeffer were implicated in the July 20, 1944, bomb plot to kill Hitler and both were executed at Flossenbuerg Prison on April 9, 1945, two weeks before the Allies arrived in the area.

Biography of Martin Niemoeller. (Amateur production but worth watching.)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click