MANILA’S LIBERATION AT HAND

Manila, Philippines · February 3, 1945

On this date in 1945, 35,000 soldiers of the U.S. Sixth Army under Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger, supported by 3,000 Filipino guerrillas, began entering Manila, capital of the Philippines, and soon liberated nearly 6,000 Allied and Filipino prisoners. Some of them, like the 64 U.S. Army nurses, were taken captive in 1942 when Bataan and Corregidor fell to Japanese invaders. Back then Manila had been quickly overrun after Gen. Douglas MacArthur declared it an “open city” to prevent its destruction and the massacre of its one million residents. But this year, 1945, the battle for Manila would stretch into a month, ending on March 3, when the city was declared totally secure. Most of the city was destroyed, a thousand American soldiers lost their lives, and over 5,500 were wounded. Killed too were more than 16,000 Japanese defenders (sailors, marines, soldiers, and civilians) cobbled together by Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi, who vowed to defend the capital to the last man. Worse yet were the huge number of Manila’s residents—100,000, or one-tenth of the city’s population—who lost their lives in the nastiest urban fighting in the Pacific Theater. Many of them were killed in their homes or shelters as the Americans ferreted out the enemy, unfortunate victims of U.S. infantrymen armed with flamethrowers, grenades, and bazookas. Others were victims of direct shelling from tanks and tank destroyers or killed in aerial bombardment. Some of the dead were among the 4,000 civilian hostages Iwabuchi had taken or were victims of Japanese looting, rape, and murder in what would later be called the Manila Massacre. The city’s eventual capture, along with that of the jungle-covered Bataan Peninsula opposite Manila and the island fortress of Corregidor in Manila Bay, capped MacArthur’s victory in the campaign to retake the Philippines. Oddly enough, as the Battle of Manila raged, the general’s staff was busy planning his victory parade. With over 230,000 Japanese troops dispersed on the islands, if no longer in Manila itself, months of hard and costly fighting lay ahead. Yet one thing was now crystal clear: the loss of the Philippines meant the end of the Japanese sea lifeline to the East Indies—sources of food, oil, metals, and rubber. It was the final blow to the survival of Imperial Japan.

![]()

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0440236959,0891417710,1410224953,0786465700,1848610106,038549565X,1933909137,1849080755,0312338341,0820321176″ /]

Scenes of Manila’s Liberation, February and March 1945

|  |

Left: Aerial view of the destruction of Manila’s Intramuros (“Walled City”) in May 1945. Intramuros was the oldest district and the historic core of the city of Manila. The quarter-square-mile district was heavily damaged during the battle to retake Manila from the Japanese, which ended almost three years of Japanese military occupation of the Philippine capital. After Poland’s Warsaw, Manila was the most heavily damaged of all Allied capitals during the war.

![]()

Right: Burned-out, battle-scarred Manila, as U.S. engineers and thousands of Filipinos begin the huge task of reconstruction. This aerial view looks southwest across the Pasig River toward the hulks of sunken ships in the harbor. Buildings in the foreground are gutted. Across the river are the burned-out general post office and the Metropolitan Opera House in ruins. The battered walls of Intramuros and the destroyed buildings inside occupy the rectangular area beyond the post office. The streets have already been cleared of rubble.

|  |

Left: Santo Tomas Internment Camp, on the campus of the University of Santo Tomas in Manila, was the largest of several camps in the Philippines in which the Japanese interned more than 4,000 enemy civilians, mostly Americans, from January 1942 until February 1945. This photo, taken on February 5, 1945, shows hundreds of camp internees in front of the university’s Main Building cheering their release. Evacuation of the internees began on February 11. Sixty-four U.S. Army nurses interned in Santo Tomas were the first to leave that day and board airplanes for the United States. Flights and ships to the States for most internees began on February 22.

![]()

Right: Emaciated internees at Santo Tomas Internment Center, February 1945. Male internees lost an average of 53 pounds during the 37 months of their captivity at Santo Tomas. Forty-eight people died in the camp in February due to the lingering effects of near-starvation for so many months. Most internees could not leave the camp because of a lack of housing in Manila, almost completely destroyed in the battle to retake the city. In March and April 1945 the camp slowly emptied out, but it was not until September that Santo Tomas finally closed and the last internees boarded a ship for the U.S. or found places in Manila to livea.

|  |

Left: Civilian survivors of the Battle for Manila, February 3 to March 3, 1945. During lulls in the battle for control of the city Japanese troops reputedly took out their anger and frustration on the civilians caught in the crossfire. An estimated 100,000 civilians died during the battle, but the proportion of casualties due to Allied artillery and heavy aerial bombardment versus Japanese troops is not known.

![]()

Right: Refugees from war-torn sections of Manila, particularly the Intramuros section where heavy fighting still continued, cross a pontoon bridge over the Pasig River to safety. The fighting for Intramuros, where Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi held around 4,000 civilian hostages, continued from February 23 to February 28. Already having decimated the Japanese forces by bombing, American forces used artillery to try to root out the Japanese defenders. However, the centuries-old stone ramparts, underground edifices, the Sta. Lucia Barracks, Fort Santiago, and villages within the city walls all provided excellent cover.

|  |

Left: Refuges from Manila’s Walled City stream out to the safety of American lines. Less than 3,000 civilians escaped the U.S. siege and assault of Intramuros, mostly women and children whom the Japanese released on February 23. Japanese soldiers and sailors killed 1,000 men and women, while the other hostages, including approximately 600 American POWs being held in the dungeons at Fort Santiago, died during the American shelling.

![]()

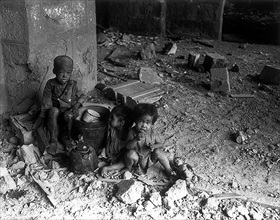

Right: Bleeding, bruised, and half starved, this little Filipino boy sits on a box in the rubble of Manila’s Walled City with two friends who were also orphaned.

Newsreel of U.S. Army Battle for Manila, Philippines, 1945

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click