JAPANESE TO BE MOVED FROM U.S. WEST COAST

Washington, D.C. · February 19, 1942

On this date in 1942 President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. It authorized the War Department to designate “military areas” in the U.S. and exclude from them anyone whom the department felt to be a danger to the security of the nation. Although the order was carefully neutral, it ultimately led to the internment of more than 110,000 persons of Japanese ancestry, citizens and noncitizens alike, living along the West Coast of the U.S. Almost three-quarters of those interned were American-born U.S. citizens, reclassified by the government as “non-aliens” to minimize any awkwardness. Almost half the internees were children. (In Canada, 20,000 Japanese Canadians and Japanese suffered similar treatment. South of the border almost 5,000 Japanese were removed from Mexico’s Pacific Coast.) Deprived of their property, Japanese American and Japanese-born internees were taken first to assembly centers, or temporary detention camps (the Santa Anita, California racetrack stables was one), then to one of ten permanent inland relocation centers where they were forced to live behind barbed wire, watched over by armed guards (see map below).

German Americans and German U.S. residents escaped a similar fate and were not interned en masse. Under the U.S. Justice Department’s Enemy Alien Control Program, the government detained and interned over 11,000 German enemy aliens, as well as a small number of German American citizens, either naturalized or native born. The population of German citizens in the United States—not to mention American citizens of German birth—was far too large for a general policy of internment comparable to that used in the case of the Japanese. Instead, German citizens were detained and removed from coastal areas on an individual basis. The evictions amounted to only several hundred. In addition, over 4,500 ethnic Germans were brought to the U.S. from Latin America and similarly detained based on a list drawn up by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The FBI suspected these Germans of subversive activities abroad and, following Germany’s declaration of war on the U.S., demanded their eviction to this country for detention or their return to Germany. Many had been residents of Latin America for years, some for decades. Nine Latin American countries and Canada set up their own Axis internment camps.

![]()

Executive Order 9066 Cleared the Way for the Forced Relocation of West Coast Japanese Americans to Internment Camps Far From Their Homes

|

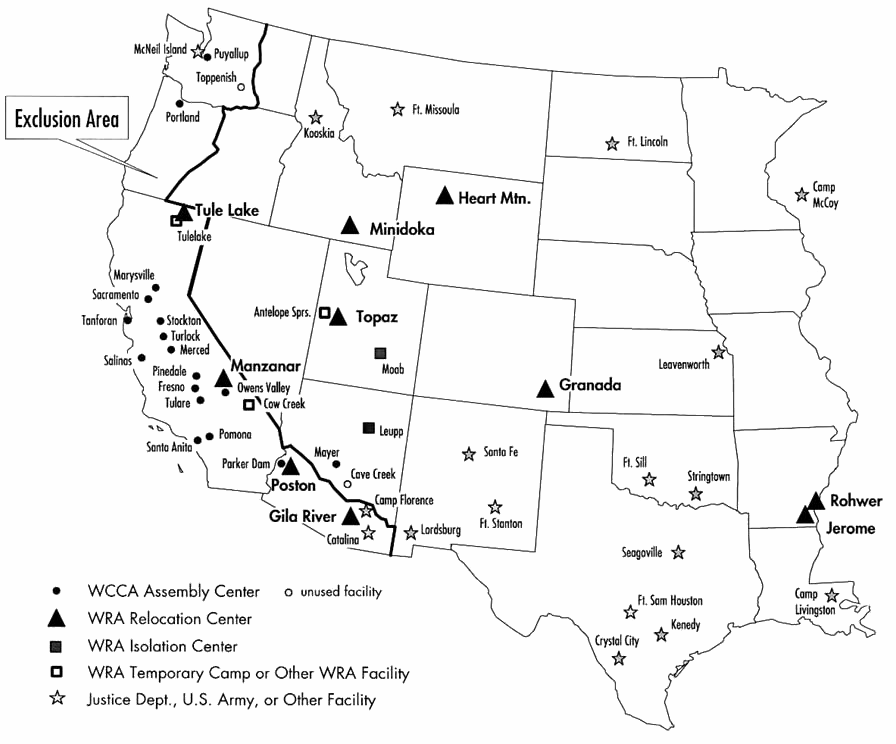

Above: Map of World War II internment camps for Japanese Americans as well as for over 31,000 suspected enemy aliens and their families interned under the Enemy Alien Control Program. (The latter camps and military facilities are indicated by stars; for example, Kooskia Internment Camp in Idaho and Fort Missoula Internment Camp in Montana.) In the map legend, WCCA = Wartime Civil Control Administration, WRA = War Relocation Authority. More than 110,000 Japanese Americans and resident Japanese aliens would eventually be removed from their homes in California, the western halves of Oregon and Washington, and Southern Arizona as part of the single-largest forced relocation in U.S. history. The Poston War Relocation Center near the Colorado River and the California border was the largest such camp in America. It became the third-largest “city” in Arizona at the time. Together with the Gila River War Relocation Center south of Phoenix, the two camps grew to hold 30,000 people of Japanese descent, most of them American citizens. In Hawaii, where 150,000-plus Japanese Americans comprised over one-third of the population, only 1,200 to 1,800 were interned.

|  |

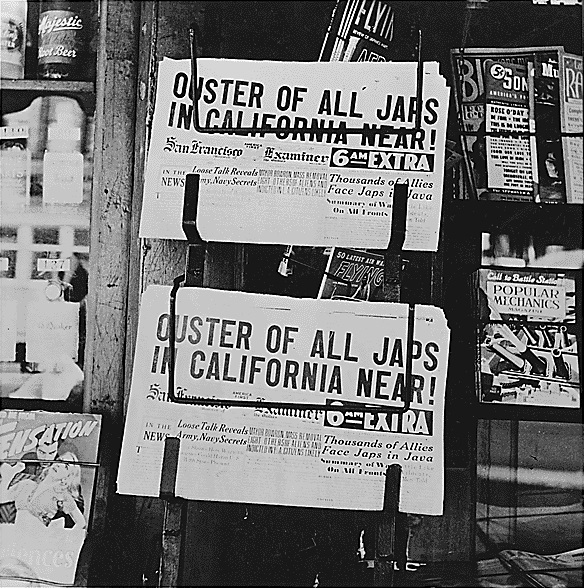

Left: “OUSTER OF ALL JAPS IN CALIFORNIA NEAR!” San Francisco Examiner headlines of Japanese relocation, February 27, 1942. Photo by Dorothea Lange. Lange was one of three photographers in the WRA Photography Section, or WRAPS, in 1942–1943. The other two were Clem Albers and Francis Stewart.

![]()

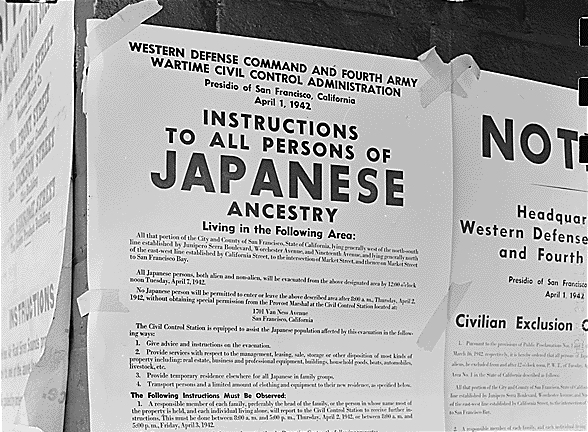

Right: Official notice of exclusion and removal, April 1, 1942. Photograph by Dorothea Lange. The posted exclusion order directed Japanese Americans living in the first San Francisco section to evacuate. Years before the December 7, 1941, Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the U.S. government had drafted plans to intern some Japanese Americans and immigrant aliens and had already placed some West Coast communities under surveillance. This in spite of years worth of FBI and naval intelligence data that attested to residents of Japanese descent posing no national security threat.

|  |

Left: With luggage tags affixed to their clothing—an aid in keeping family units intact during all phases of their forced removal—members of the Mochida family await an evacuation bus, Alameda County (San Francisco Bay area), California, May 8, 1942. On the luggage tags was written the family’s designated identification number. The Mochidas had operated a two-acre nursery and greenhouse in Eden, Alameda County, before the family’s incarceration. Photograph by Dorothea Lange.

![]()

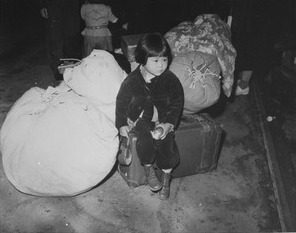

Right: Staring into uncertainty 2-year-old Yuki Okinaga Hayakawa, clutching a tiny purse and an apple with a few bites gone, waits with the family’s allotment of baggage before leaving Union Station in Los Angeles, eventually arriving with her mother at Manzanar War Relocation Center, more than 200 miles away in California’s Owens Valley, which would be her home for the next 3 years. Each family member was permitted to take bedding and linens (no mattress), toilet articles, extra clothing, and “essential personal effects,” nothing more; in other words, only what could be carried. Photograph by Clem Albers.

|  |

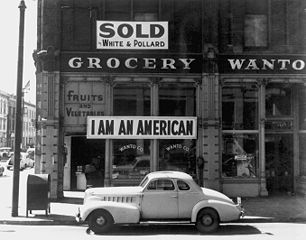

Left: This Oakland, California green grocer closed his store in March 1942 following orders to persons of Japanese descent to evacuate from certain West Coast areas (Military Area 1; see map above). The owner, a University of California graduate, had placed the “I AM AN AMERICAN” sign on his store front on December 8, the day after Pearl Harbor. Declarations like this San Francisco area store owner’s were insufficient to overcome the suspicion and contempt directed at people who looked like the enemy and who, it was commonly assumed at the time, remained loyal to Japan and its emperor Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa). Photograph by Dorothea Lange.

![]()

Right: In 1944 the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the exclusion orders, described by many Americans as the worst official civil rights violation in modern U.S. history. After years of lawsuits and negotiations, on August 10, 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which formally acknowledged that the wartime exclusion, evacuation, and internment of Japanese Americans had been unreasonable. The act granted $20,000 in reparations to each surviving Japanese American (about 82,000 people), costing the U.S. Treasury $1.6 billion. It took a decade to locate all eligible U.S. recipients and deliver them their checks and formal apology. A late 20th-century study concluded that the internal government decisions that led to Roosevelt issuing Executive Order 9066 were based on racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and failed political leadership.

Injustice Camouflaged as Military Necessity: Japanese American Internment During World War II

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click