JAPANESE NAVY ORDERS SHIPWRECK SURVIVORS SHOT

Japanese Naval Base, Truk Lagoon, South Pacific • March 20, 1943

Although Japanese submarines attacked far fewer ships than the Allies or Germany did, they were involved in a dozen or so documented atrocities—naval war crimes—against crew survivors. On this date in 1943 Rear Admiral Takero Kouta, commander of the First Submarine Group at the large Japanese naval base at Truk (today known as Chuuk), instructed naval personnel to not only sink enemy ships and cargoes but to completely eliminate any survivors, reputedly in retaliation for the alleged slaughter of Japanese merchant ship crews by Allied submarines.

On May 14, 1943, Hajime Nakagawa, the most notorious Japanese submarine commander, ordered his I‑177 to sink the Australian hospital ship Centaur, which was steaming unarmed and unescorted 50 miles northeast of the port of Brisbane, Queensland. Only 64 of her 332 crew and medical personnel survived. Commanding the I‑37 on her third patrol at the start of 1944, Nakagawa sank the 7,118‑ton armed tanker British Chivalry after it had departed from Melbourne, Australia, in February 1944, machine-gunning 39 out of 59 crewmen in lifeboats. He employed the same tactics 12 days later when he ordered his crew to open fire on the survivors of the 5,189‑ton British armed vessel Sutlej sailing unescorted in the Arabian Sea en route to the West Australian port of Fremantle. A total of 41 sailors and nine gunners were killed, while 21 sailors and two gunners, adrift in two separate lifeboats, survived and were picked up over 40 days later by two British vessels.

On February 29, 1944, the I‑37 fired two torpedoes at the 7,005‑ton British armed cargo steamer Ascot. After scuttling the wreck by shellfire, the I‑37 sank the steamer’s lifeboat with its 52 occupants. Four sailors and three gunners were rescued four days later by a Dutch steamer. The I‑37 was responsible for the death of 118 seamen in just three attacks before it was sunk by destroyer escorts USS Conklin and USS McCoy Reynolds off Palau in the Philippine Sea on November 19, 1944, with a loss of all 113 hands. By then Nakagawa had been replaced as commander. When sunk, the I‑37 was outfitted with four Kaiten, which were manned suicide torpedoes. At the postwar Tokyo war crime trials, Nakagawa, who never faced trial for sinking the Centaur (investigators believed they could not make a definitive case), was sentenced to eight years’ hard labor at Sugamo Prison after pleading guilty to machine-gunning survivors of British vessels he sank while commanding the I‑37. Nakagawa was released on probation after six years following the end of the Allied occupation.

Lt. Cdr. Hajime Nakagawa of the Japanese Navy and the Sinking of the AHS Centaur off the Coast of Queensland, May 14, 1943

|

Above: I-176, a submarine of the same Kaidai VII class as I‑177. Commanded by Lt. Cdr. Hajime Nakagawa, I‑177 torpedoed the AHS Centaur off the Australian east coast on May 14, 1943. The hospital ship went down in shark-infested waters in three minutes for a loss of 268 persons. The Japanese government issued a statement denying responsibility for sinking the Centaur, an act considered a war crime, but in 1979 the Japanese Navy accepted ownership of the deed. A U.S. Navy destroyer escort sank I‑177 on October 3, 1944, with the loss of her entire crew of 101 sailors.

|  |

Left: AHS Centaur following her conversion to a hospital ship. A 5‑ft‑high green band of paint encircled the white ship. Three Geneva Red Cross symbols can clearly be seen near her bow, middle, and stern. In the early morning hours of May 14, 1943, the day she was torpedoed, the Centaur was brightly illuminated by electric lights, including lights directed on the Red Crosses on her sides and the International Red Cross designation “47” on her bows. After sinking the hospital ship, Lt. Cdr. Nakagawa surfaced, maneuvered the I‑177 toward the survivors, then slid under the waves.

![]()

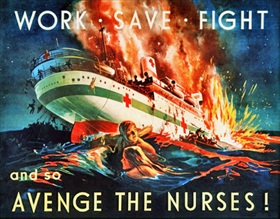

Right: A propaganda poster calling on Australians to avenge the deliberate sinking of the Australian hospital ship Centaur by a Japanese submarine. Allied submarines had inadvertently sunk Japanese hospital ships because the Japanese did not clearly or properly mark them in accordance with International Red Cross guidelines. That was true of unmarked Japanese merchant vessels torpedoed by Allied submarines, which resulted in the deaths of thousands of Allied POWs in transit in the holds of so-called “hellships.”

Imperial Japanese Navy Submarine on Duty in Pacific Ocean During Early Part of World War II

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click