GERMANS, SOVIETS INK ECONOMIC DEAL

Berlin, Germany • August 20, 1939

In the early morning hours on this date in 1939 the first of two back-to-back seismic changes to Europe’s political, economic, and geostrategic equilibria occurred with the signing of the German-Soviet Trade and Credit Agreement in Berlin. An outgrowth of monthslong economic and political talks between German and Soviet representatives bent on improving bilateral relations, the economic deal between the two long-term ideological rivals was the essential prelude to a second agreement, the 10‑year German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact with its secret protocol for dismembering Poland, sealed days later in Moscow’s Kremlin.

The August economic agreement was crafted to give Nazi Germany access to the Soviet Union’s agricultural products, metal ores, rubber, and oil, of which the former country was an habitual net importer—e.g., importing 20 percent of its foodstuffs, 60 percent of its iron ore, 100 percent of its chrome and manganese, 80 percent of its rubber needs, and 66 percent of its oil by 1939. In return the Soviet Union, having embarked on its third Five-Year Plan in 1938, was to gain access to hard currency (a 7‑year credit line of 200 million German Reichmarks, roughly equivalent to 69 million U.S. dollars), industrial equipment such as diesel engines and locomotives, technological know-how, manufactured items like piston rings and spark plugs, and precious military wares (warships, fighter and bomber aircraft, tanks, field artillery, gun sights, bombs, and ammunition, for example) to strengthen its weakened defense forces as well as modernize its creaking industrial sector. The rapproachement embodied by the twin pacts allowed Adolf Hitler, who now had a friendly frontier to his east, to loose his armed services on Poland, propelling Great Britain and France into World War II.

The German-Soviet Trade and Credit Agreement initially disappointed its German supporters, who had advocated rejuvenating economic cooperation and trade between Berlin and Moscow in the face of an anticipated British maritime blockade of their country. Over the six months that followed its signing, both sides engaged in occasional bad faith as they finessed, reinterpreted, amended, or refused to compromise over still-outstanding details; delayed agreed-on reciprocal deliveries of raw materials and finished goods; procrastinated by throwing up reams of red tape; inflated prices; and provoked occasional spats that required the highest levels of political intervention. Revisions in February 1940 and January 1941 eliminated the most critical deficiencies in previous treaties and upped the value of their bilateral exchange by hundreds of millions of Reichmarks (RM).

By mid-1941 the Germans had tapped into the Soviet Union’s vast strategic natural resources for a year and a half, while their trading partner was the recipient of valuable manufactured goods and services. By way of example, on the German side between February 1940 and June 1941, that worked out to 900,000 tons of oil, 660,000 tons of metal ores (e.g., manganese, chrome, and iron), 18,000 tons of rubber, 200,000 tons of cotton, and 1.6 billion RM in grains (20 percent of the amount of the total German harvest). At its high point in 1940, the combined value of trade is estimated at 646 million RM (about $258 million), with the Soviets selling 404 million RM of commodities to Germany and Germany delivering 242 million RM worth of goods to the Soviet Union.

The short-lived age of German-Soviet détente and cooperation ended in the ear-splitting sound of rolling thunder as Hitler’s legions of aircraft, tanks, artillery shells, and over three million battle-hardened men poured over the Soviet frontier on June 22, 1941.

![]()

German-Soviet Economic and Political Cooperation, August–September 1939

|  |

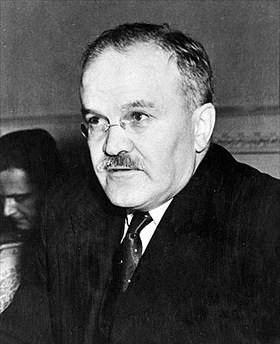

Left: Soviet People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov wrote in Pravda, the official mouthpiece of the Soviet Communist Party, that August’s commercial agreement was “better than all earlier treaties” and “we have never managed to reach such a favorable economic agreement with Britain, France, or any other country.” Early in the morning of August 24, Molotov and his German counterpart, Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, signed the political and military treaty, the Molotov–Ribbentrop Nonaggression Pact that was the companion piece to the earlier commercial deal. (The second treaty bears the date August 23, 1939.) In effect a neutrality agreement between the two countries, the Molotov–Ribbentrop treaty contained a secret protocol for dividing the states of Northern and Eastern Europe into German and Soviet “spheres of influence.” Interestingly, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin considered the trade deal at the time to be the more important of the two Nazi-Soviet pacts, for it had the potential to return bilateral trade to levels last seen in the 1920s and early ’30s. Hitler placed his bet on the follow-up nonaggression pact, waiting just long enough for the ink to dry before ordering his attack on Poland on September 1, 1939, and plunging all Europe into World War II.

![]()

Right: Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov signs the German-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Demarcation in Moscow on September 28, 1939, in the presence of Stalin (light tunic) and a framed portrait of Vladimir Lenin, Soviet first head of state. Standing to the right of Stalin is Molotov’s opposite number, German Foreign Minister von Ribbentrop, who signed for Germany. The September treaty supplemented the initial secret protocol in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Nonaggression Pact signed the month before between the two countries prior to their joint invasion and occupation of their mutual neighbor Poland and the start of World War II in Europe.

Prelude to World War II in Europe: The Molotov-Ribbentrop Nonaggression Pact of August 23, 1939, Named After Its Two Signatories

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click