GERMANS SOON DOWN TO LAST BARREL OF OIL

London, England · September 21, 1944

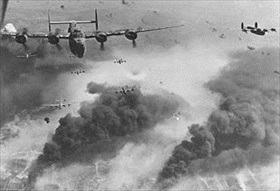

On this date in 1944 some 147 of 154 dispatched B‑17 Flying Fortresses bombed the synthetic oil plant at Ludwigshafen, an industrial city on the Rhine River in West-Central Germany. The sortie was one of seven (for a total of more than 1,400 B‑17s) that unloaded high-explosive and incendiary bombs on the Ludwigshafen synthetic oil plant in September 1944. The production of synthetic fuel, which was laboriously extracted from low-grade lignite coal, had become critical to Nazi Germany’s war machine after the Ploesti (Ploieşti) oil refineries in Romania suffered damage in August 1943 and even greater damage in the spring and summer of 1944 from B‑24 Liberators based first in Benghazi, Libya, then in Southern Italy.

Before that, in June 1942, the year U.S. aircraft first tried to destroy the Romanian complex, Ploesti produced nearly a million tons of refined oil a month, most of which, including the highest-quality 90‑octane aviation fuel in Europe, went to the Axis war effort. Indeed, over a third of Germany’s petroleum needs were met by Ploesti, and because of this Ploesti was the most heavily defended target in the Third Reich, even more than Berlin, the Nazi capital. Fifty thousand well-trained Germans manned the perimeter of the dozen refineries that made up the oil complex, firing 88s (88mm), 20mm, and 37mm fast-firing cannon from specially built flak towers, some disguised as haystacks. Heavy machine guns sprouted from factory rooftops. A German early warning system that stretched to Axis-occupied Greece in the south could send swarms of Axis fighters from local airfields to intercept incoming B‑17s.

During the war 60,000 Allied airmen flew against the “graveyard” of the U.S. Fifteenth Air Force, as Ploesti was later called, dropping 13,000 tons of bombs. Eventually they knocked out much of the oil complex. But no amount of synthetic oil production at Ludwigshafen or elsewhere in the Third Reich overcame losses from Ploesti. Despite the successes of thousand-plane Anglo-American air raids on German aircraft and munitions factories, U‑boat and rail yards, ball bearing factories, V‑weapon launch sites, and other ultra-high-value targets, it was the Allies’ air campaign against petroleum and synthetic oil plants that deprived Nazi Germany of the essential fuel to sustain its war against the Allies.

![]()

![]()

Deadly Tidal Wave: The U.S. Air Raid on the Ploesti (Ploiești) Oil Complex, August 1, 1943

|  |

Left: Early Sunday morning, August 1, 1943, five bomber groups—178 B‑24s carrying 1,780 flyers—comprising Operation Tidal Wave lifted off from airfields around Benghazi, Libya, for the 2,700 mile round trip to Ploesti, 35 miles north of Romania’s capital, Bucharest. Ploesti consisted of close to a dozen oil refineries that provided a reliable third or more of the petroleum that fueled German aircraft, tanks, battleships, and U‑boats. Ploesti was the “taproot of German might,” said British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The epic August 1 air raid—the biggest staged to date—turned out to be one of the costliest for the U.S. Eighth (transferred from England) and Ninth Air Forces. For several Eighth Air Force B‑24 squadrons, fresh from flight school in the United States, the August attack on Ploesti would be their first and last combat mission. In this photo a half-dozen huge four-engine, easy-to-hit B‑24Ds muscle their way through Ploesti’s extensive air defense arrays

![]()

Right: By the time the U.S. air armada had crossed into Romanian air space, Ploesti’s air defenses were coming to full alert. They included several hundred 88mm (3.46‑in) and 105mm (4.1‑in) antiaircraft guns. Many more small-caliber guns were concealed in barns, haystacks, railroad cars, and mock buildings. In addition the Luftwaffe had three fighter groups within flight range of Ploesti assisted by some Romanian fighter aircraft. On top of these dangers, balloon cables, tall cracking towers, raging oil fires, heavy acrid smoke, secondary explosions, and delayed-fuse bombs from the strikes of the lead bomb groups increased the risks facing succeeding waves of B‑24s flying 200 feet or lower off the ground. Many of the planes that returned home had flown so close to the ground that cornstalks were stuck in their bomb bays.

|  |

Left: Scarcely 30 minutes after the air raid had begun, the last bombs were dropped by the 167 B‑24s that had reached Ploesti. The surviving B‑24s fled west with all the speed they could muster, trying to form up as best as they could for the long return flight to Benghazi. Only 88 out of the original 178 B‑24s made it back, and of these 55 were battle damaged by heavy antiaircraft defenses and Axis fighter aircraft. August 1, 1943, was later referred to as “Black Sunday.” Some B‑24s were forced to ditch in the Mediterranean Sea. Eight landed in neutral Turkey, while 23 were diverted to airfields on Malta, Sicily, and Cyprus. Three hundred and ten crewmen were killed, some hitting the ground before their parachutes could open. Another 108 were captured and 78 were interned in Turkey.

![]()

Right: Columbia Aquila refinery after the air raid, bomb-cratered but largely intact. An overall appraisal of the bomb damage at Ploesti indicated no long-term curtailment of overall production output, only a drastic reduction in storage capacity. Much of the observed smoke and flames came from burning storage tanks that held finished products, not from the destruction of cracking towers, steam plants, and critical pipeline junctures. Given the large and unbalanced loss of aircraft and crewmen and the limited damage to the complexes (only one refinery stayed out for the duration of the war), Operation Tidal Wave was deemed a strategic failure. Indeed, Ploesti remained in operation until it was overrun by advancing Soviet troops in August 1944.

Severing Hitler’s Oil Pipeline: The Allied Bombing Campaign Against Romania’s Ploesti Oil Complex

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click