GERMANS OVERWHELM DUTCH DEFENDERS

Rotterdam, Netherlands · May 14, 1940

On this date in 1940 in Holland, the German Luftwaffe bombed Rotterdam’s medieval city center, killing nearly 1,000 people and leaving 85,000 homeless. Rather than endure more bombings—leaflets dropped on Utrecht indicated it was next Dutch city in German crosshairs—the Dutch Army surrendered the next day. The German offensive against the Low Countries had been launched four days earlier, on May 10, without a declaration of war beforehand, when German airborne/airlanding assault divisions and ground forces began seizing strategic locations in Holland and Belgium.

The surprise assault on the Low Countries was part of Fall Gelb (Case Yellow), a German operation that included attacking France, which, like Great Britain, had been at war with Germany since September 3, 1939, two days after Adolf Hitler had unleashed the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) on his eastern neighbor, Poland. Fighting continued along the Dutch-Belgian border, where several Dutch battalions, aided by French units, put up a limited defense.

It was in Belgium, in principle neutral, that France moved to halt the German advance, believing its northern neighbor to be the Wehrmacht’s main thrust in the West. After the French had fully committed the best of their armies in defense of Belgium between May 10 and 12, the Germans enacted the second phase of Fall Gelb, a sickle-cut through the heavily forested and rough terrain of the Ardennes in Southern Belgium and Luxembourg, devoid of Allied forces, and advanced toward the northern French coast.

The Germans reached the English Channel after five days, encircling the French, Belgian, and British armies. (A British Expeditionary Force had been deployed mainly along the Belgian-French border since September 1939.) The Germans gradually shrank the Allied pocket to the beaches and harbor at Dunkirk. The Belgian Army capitulated on May 28, 1940. The Germans would have totally annihilated the British and French armies had it not been for the extraordinary impromptu evacuation of 198,229 British and 139,997 French servicemen from Dunkirk between May 27 and the morning of June 4, 1940. The “Miracle of Dunkirk” provided a psychological boost to British morale, and the rescued British troops provided the nucleus of the British Army that returned to help liberate the continent in 1944.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0809089068,0785820973,0393319113,0674024397,1782006443,0141030658,0395410568,1611453143,1846034574,0192805509″ /]

German Invasion of the Low Countries and France; Dunkirk Rescue

|  |

Left: Rotterdam’s burning city center after the bombing. The Germans called such bombings Schrecklichkeit—“frightfulness.” After the Luftwaffe targeted Rotterdam in what became known as the Rotterdam Blitz, the Royal Air Force abandoned its policy of not deliberately bombing civilian property in Germany. On the night of May 15/16, 1940, the RAF made its first raid on the interior of Germany, attacking civilian industrial targets in the Ruhr district that aided the German war effort.

![]()

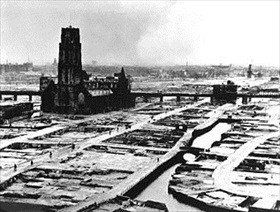

Right: The heavily damaged Laurenskerk (St. Lawrence Church) and Rotterdam’s medieval city center after the removal of bomb debris. Around one square mile of the city was nearly leveled in less than an hour, and 24,978 homes, 24 churches, 2,320 stores, 775 warehouses, and 62 schools were destroyed.

|  |

Left: Rescued British troops gathered on a ship at Dunkirk (Dunkerque), Northern France, where, according to Prime Minister Winston Churchill, “the whole root, core, and brain of the British Army” was trapped. For every seven British and French soldiers who were rescued in what was named Operation Dynamo, one man was left behind as a prisoner of war, eventually ending up in Germany. Those below the rank of corporal worked as slave laborers in German industry and agriculture for the duration of the war.

![]()

Right: Dunkirk-rescued French troops disembarking at a port on the south coast of England. Of the French soldiers evacuated from Dunkirk, only about 3,000 chose to continue the struggle against Nazi Germany, joining Charles de Gaulle’s Free French Forces (Forces françaises libres) in London. The rest were repatriated back to France, where about one half were redeployed against the Germans before the Franco-German armistice at Compiègne was signed on June 22, 1940, after which they were made POWs by the German Army.

Winston Churchill’s Speech to the House of Commons, June 4, 1940: “We shall fight them on the beaches, . . . and we shall never surrender”—His Account of the “Miracle of Dunkirk”

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click