FIRST BOOTS ON JAPANESE SOIL ARE ARMY BOOTS

Kyūshū Island, Japan • August 25, 1945

On this date in 1945, ten days after Japanese Emperor Hirohito had announced his agreement to surrender his nation unconditionally, two U.S. Army pilots flying P‑38 Lightnings on armed reconnaissance landed at Nittagahara Airfield on Kyūshū Island, the southernmost Japanese Home Island, after one of the P‑38s ran low on fuel. The two pilots became the first Americans to land in defeated (though not yet occupied) Japan. An hour later, in the presence of Japanese Army personnel, a B‑17 Flying Fortress landed on the same airfield to assist the two pilots in refueling the plane for its return flight to Okinawa.

The Japanese reception was friendly, even formal—the local mayor appeared in top hat and tails. All three crews were three days ahead of Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s advance team, which landed at Japan’s largest airfield, Atsugi Naval Air Base outside Tokyo, to coordinate the official signing ceremony in Tokyo Bay on September 2. To welcome the advance team, a mischievous naval fighter pilot from the USS Yorktown, which was providing cover for the forces occupying Japan, landed his plane at Atsugi on August 27 and ordered the Japanese to erect a banner welcoming the Army general on “on behalf of the U.S. Navy.” Banners on Tokyo streets proclaimed: “Welcome the American victories all over the world.”

On September 2, six years and a day after Germany precipitated the global conflict by invading neighboring Poland, MacArthur headed the Allied delegation on board the battleship USS Missouri that brought World War II to an end by accepting Japan’s formal surrender. The 887‑ft, 45,000‑ton “Mighty Mo” lay exactly four and one-half miles northeast of the spot where, on July 8, 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry had anchored four small ships of the U.S. Navy’s Far East Squadron, which flew an American flag of thirty-one stars. Ninety-two years after the “opening of Japan,” Perry’s flag (known as an ensign) was on prominent display when an 11‑member Japanese delegation, traveling through burnt-out cities, arrived at its destination. The Japanese signed the surrender document at 9:05 a.m. Gen. MacArthur signed for the United Nations and U.S. Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, who had directed much of the Pacific War, signed for the United States. Minutes later, in a show of the massive air power that had ended the Pacific War, 1,500 carrier aircraft and 500 B‑29s flew over the armada of U.S. and British ships that filled Tokyo Bay. It was a thunderous and fitting conclusion to the proceedings.

![]()

Japanese Sign the Instrument of Surrender Aboard USS Missouri, September 2, 1945

|  |

Left: The 11-member Japanese delegation of civilians and military officers shortly after their arrival on board the USS Missouri, Sunday, September 2, 1945. Leading the delegation was Foreign Affairs Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu (top hat with cane). Signing the Instrument of Surrender for the Japanese military was Gen. Yoshijirō Umezu (to Shigemitsu’s left). In 1948 Shigemitsu was sentenced to seven years imprisonment by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. Paroled in 1950 Shigemitsu became Deputy Prime Minister of Japan in 1954. Umezu, final Chief of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff and a member of Emperor Hirohito’s Supreme Council for the Direction of the War (Saikō sensō shidō kaigi), was tried as a war criminal by the same tribunal, which sentenced him to life imprisonment. He died in prison in 1949.

![]()

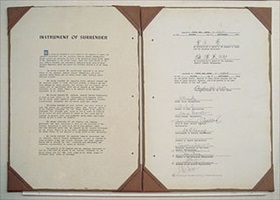

Right: The Japanese Instrument of Surrender was the written agreement that enabled the surrender of the Empire of Japan, marking the end of World War II. It was signed by representatives from Japan, the U.S., China, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, Australia, Canada, France, the Netherlands, and New Zealand aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945. The Allied copy was presented in leather and gold lining with both countries’ seals printed on the front, whereas the Japanese copy shown here was bound in rough canvas with no seals on the front. In 1951 Japan concluded a peace treaty with the U.S. and other Allied nations and the following April the country formally regained its independence.

|  |

Left: Dressed in khaki and an open-neck shirt, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Allied Commander, opened the 20‑minute surrender ceremony on the starboard veranda deck of the USS Missouri precisely at 9 a.m. Forty-three high-ranking officers from eight Allied powers (United Nations) are lined up behind him. Mounted on the bulkhead behind the rows of men is the 31‑star ensign (the blue canton displayed correctly) that Commodore Matthew Perry had brought ashore to Japan in 1853. The fragile flag was retrieved from the Naval Academy’s museum in Annapolis, Maryland, and delivered on August 29, 1945, to Adm. William “Bull” Halsey, Commander of the U.S. Third Fleet, whose flagship was the Missouri. Also present were the Stars and Stripes that had flown over the U.S. Capitol on Sunday, December 7, 1941. Just before closing the proceedings, MacArthur intoned, “Let us pray that peace now be restored to the world, and that God will preserve it always.” Victor in war, MacArthur stayed on in Japan to manage the peaceful seven‑year U.S. occupation of that country.

![]()

Right: Some 1,900 Allied bombers and carrier planes fly in precise formation over the U.S. and British fleets assembled in Tokyo Bay, September 2, 1945. The USS Missouri is at left. On the battleship’s surrender deck were over 130 official guests, or delegates—American, British, Chinese, Soviet, Australian, Canadian, French, Dutch, and New Zealand officers—who were invited to witness Japan’s formal capitulation. The impressive U.S. delegation included 39 generals and 34 admirals, among them Lt. Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright who surrendered the beleaguered Philippines to the Japanese invaders, Lt. Gen. James H. Doolittle, and Maj. Gen. Curtis E. LeMay, the later two generals having famously brought the war home to mainland Japanese. The British delegation was headed by Gen. Arthur Percival, who relinquished Singapore to its fate. The ship’s complement of 3,000 officers and bluejackets, plus media people, watched the surrender ceremony and flyover from atop gun turrets and walkways.

Contemporary Newsreel Accounts of U.S. Forces Landing in Japan, September 1945

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click