U.S. FIFTH ARMY IN RACE TO ROME

With Maj. Gen. Mark Clark in Italy · May 25, 1944

In 1943–1944 the centerpiece of German defenses in Italy was the Gustav Line, whose most famous bastion was centered on the historic Benedictine abbey of Monte Cassino. Thousands of German soldiers and conscripted Italian civilians worked hard to strengthen the line, 65 miles north of Naples, under orders from German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring to make it so strong that Anglo-American forces would “break their teeth on it.” Adolf Hitler himself had ordered the Gustav Line (see map below) defended “in a spirit of holy hatred not only against the enemy, but against all officers and units who fail in this decisive hour.” On the opposing side Allied commanders, in order to help their forces pierce the heavily fortified line and move up the Italian boot from bases in the south, planned amphibious landings at Anzio and Nettuno, which lay north of the Gustav Line and just 35 miles south of Rome. The amphibious landings by 37,000 American, British, French, Polish, and Canadian troops began on January 22, 1944, but within days they were pinned down to a shallow beachhead. German bombardment of the trapped men inflicted demoralizing casualties, among the Canadians disproportionately so. In four months’ time 72,000 men were killed, wounded, captured, or went missing—making Anzio the costliest purchase of ground ever by Allied forces during the war. Finally on this date in 1944 the northward-driving U.S. Fifth Army front under Maj. Gen. Mark Clark merged with the Anzio beachhead and raced toward Rome, which they occupied on June 5. Instead of cooperating with the British Eighth Army in rounding up Kesselring’s Tenth Army, in full retreat from the Gustav Line, Clark in his glory-seeking race to the “Eternal City,” emptied of German troops, so infuriated its commander, Lt. Gen. Oliver Leese, successor to Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, that Clark and Leese henceforth fought separately in Italy with only the merest pretense of cooperation. Anyway, Clark’s glory days lasted less than 48 hours, ended by genuine heroes who threw themselves at genuine opponents on D-Day in Normandy, France. Almost as fast as the media lost interest in Clark’s Roman theatrics, the American became Kesselring’s favorite enemy general because Clark always gave the German staff an easier time than they expected.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”1612001319,0312373961,0307888002,0743216423,0826217389,1841769134,0802143261,080508861X,0060576499,1844860590″ /]

Anzio and the Rome Breakout, January to June 1944

|

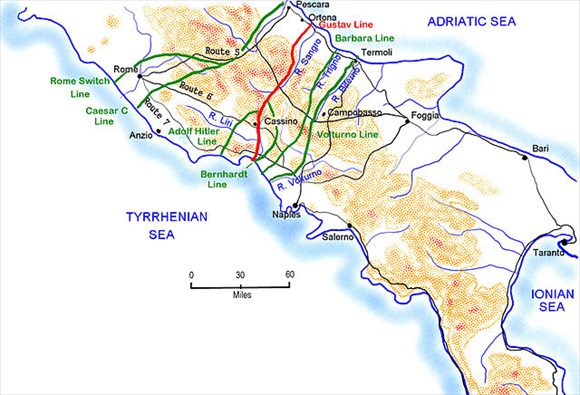

Above: German-prepared defensive lines in Italy south of Rome, 1943–1944. The primary line was the Gustav Line (red line on map), often called the Winter Line, centered on the town of Cassino. High above Cassino was an ancient Benedictine abbey, Monte Cassino, which dominated the entrance to the Liri Valley, one of two main routes to Rome, 30-some miles away. Rome was the strategic prize which the Germans fought to keep and the Allies sought to take.

|  |

Left: U.S. soldiers of Company A, 3rd Ranger Infantry Battalion board landing craft that will take them to Anzio. Two weeks later nearly all would be killed or captured.

![]()

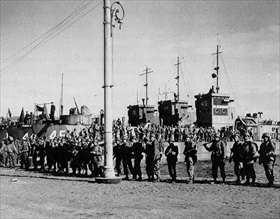

Right: U.S. Army troops landing at Anzio in late January 1944 as part of Operation Shingle, a bold plan pushed by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to end the stalemate in Italy. Shingle was commanded by U.S. Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas, who was given the task of outflanking German strongpoints along the Winter Line and enabling an attack on Rome, 40 miles north of Anzio. The divisions at Anzio would link up with Allied forces farther south and break the stalemate.

|  |

Left: A Sherman tank of the 23rd Armoured Brigade attached to the British Eighth Army coming ashore from a landing craft at Anzio on the first day, January 22, 1944. The Allies practically strolled ashore, taking the Germans completely by surprise. Unfortunately, Lucas failed to take advantage of the element of surprise. Within 48 hours of landing, Lucas had snatched defeat from the jaws of victory by ordering his two divisions to dig in instead of march on Rome.

![]()

Right: German soldiers take captured Allied wounded to a first-aid station near Nettuno, March 6, 1944. Kesselring’s Tenth Army, which Clark’s Fifth Army intelligence severely underestimated, quickly massed ten divisions of armor and men, several of them crack combat units. Not since the Blitzkrieg of spring 1940 had Germans gathered such a large attacking force to do battle with the Western Allies.

|  |

Left: German paratroopers position an artillery piece near Nettuno. Because the Allies had failed to move inland and seize the Alban Hills, the Germans were able to look down on each inch of the beachhead and on the town of Anzio itself.

![]()

Right: A 4.2-in mortar of 1st Infantry Brigade’s support group, firing in support of the 5th Northamptonshire Regiment in the Anzio beachhead, May 18, 1944. Several days later the regiment was on its way to Rome.

U.S. Fifth Army Report from the Anzio Beachhead, January to March 1944

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click