U.S. A-BOMB INCINERATES HIROSHIMA, JAPAN

509th Composite Group HQ, Tinian, Mariana Islands • August 6, 1945

For several months the U.S. had dropped more than 63 million leaflets across Japan, warning civilians of devastating aerial bombings and to evacuate the cities identified in the leaflets. Radio broadcasts from the American-held island of Saipan underscored the printed warnings. Many Japanese cities suffered terrible damage from napalm bombs that set their wood-frame buildings on fire. On August 1, 1945, in the largest bomb raid suffered by Japanese cities, 80 percent of Hachioji, a rail choke point near Tokyo, was burned out by napalm; 65 percent of Nagaoka was wasted the same day. Nearly 100 percent of Toyama, an aluminum-producing city, was incinerated. On August 5 four more Japanese cities were turned into smoking ruins. The areas destroyed and the number of people killed in U.S. air raids on Japan up till then exceeded the areas destroyed and the lives lost in all German cities by the U.S. and Royal air forces combined between May 15, 1940, and the end of the war in Europe five years later.

On this date, August 6, 1945, things were different. Seventy-eight years ago today, Hiroshima, a city of 280,000 civilians and 43,000 soldiers on the Japanese mainland of Honshū, was incinerated by a 5‑ton uranium-filled bomb codenamed “Little Boy,” the first of two atomic bombs ever dropped on an enemy nation. A blinding flash lasting perhaps a tenth of a second created an earsplitting explosion that blew out windows 6½ miles from the epicenter—Hiroshima’s city center—and sent a massive column of debris and smoke miles high.

Allied forces were poised for invasion hundreds of miles from the Japanese Home Islands when the first atomic bomb exploded. Remembrance of the horrific casualties inflicted by a fanatical enemy on Americans assaulting Japan’s offshore islands of Iwo Jima and Okinawa (February 19 to June 22, 1945)—nearly 70,000 dead and wounded—forebode worse numbers ahead, as high as one million Allied servicemen and millions more Japanese. (Actually, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff estimated likely American casualties of 31,000 during the first month of Operation Olympic, the invasion of the southern island of Kyūshū; the one million figure was ginned up after the war.) President Harry S. Truman and American commanders fretted that a war-weary public might have neither the patience nor the stomach for a Japanese-style Armageddon on Japan’s home turf.

After the Hiroshima bombing, the White House issued a statement that promised Japan “a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on earth” if the country’s military leadership did not end the war in 48 hours on U.S. terms. To a group of Christian leaders Truman explained his motives for deploying the atomic bomb: “When you have to deal with a beast you have to treat him as a beast.” (The President shared the view held by most white Americans that the Japanese were not quite human.) Considering the religious character of those he addressed at the time, Truman expressed no moral qualms about snuffing out tens of thousands of innocent lives along with the lives of the guilty—the military die-hards who refused to admit defeat.

Japanese leaders had expected, indeed planned for a brutal, no-holds-barred land invasion beginning in October. But nothing in their past experience or in their wildest imaginations had prepared them for this level of aerial immolation on that warm August morning. The deadly new weapon system was the equivalent of 220 fully loaded B‑29 heavy bombers dropping their loads in an instant. Within minutes of the bomb’s brilliant flash and earsplitting crack 40,000 Hiroshima men, women, and children died mostly in the firestorms set off by the enormous blast. People within a third of a mile (500 meters) of ground zero (hypocenter) were instantly incinerated. Hundreds, maybe thousands simply suffocated, as the explosion consumed oxygen in the blast area, leaving little of the element left for people to breathe. A further 90,000–166,000 victims would die of burns and radiation within days or weeks. Survivors of the blast, hibakusha (lit. “explosion-affected people”), lived out their lives with the fear of contracting radiation-related disorders (many succumbed years later to leukemia or other cancers) or passing malignant genetic diseases onto their children.

![]()

Hiroshima Atomic Bomb: Delivering a Foretaste of National Apocalypse

|  |

Left: Ground level photograph of the Hiroshima radioactive mushroom cloud taken from approximately 4.3 miles northeast of ground zero, the commercial center and residential area of the city. “Little Boy,” as the uranium‑235 bomb was nicknamed, detonated 1,900 ft above the Shima Hospital and 550 yards from the bombardier’s aiming point, the Aioi Bridge. Three days later another mushroom cloud appeared over the city of Nagasaki, the product of “Fat Man,” as the plutonium‑239 bomb was called. Less than a minute after falling earthward, the bombs transformed both cities into rubble. (They also transformed the world, though very differently.) The following day Japan capitulated.

![]()

Right: Lost image found in Honkawa Elementary School in 2013 of the Hiroshima radioactive mushroom cloud, believed to have been taken 20–30 minutes after detonation from about 6.2 miles east of ground zero. Some 400 Honkawa students and more than 10 teachers were victims of the bomb blast. Survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki often use the term pika-don, which translates as “flash-bang” or “flash-boom,” to describe how the atomic weapons produced a blinding light before the explosion. They find their term succinctly captures the dazzling sight and thundering sound they experienced up close.

|  |

Left: The best-known photographs of the bomb’s aftermath were taken from the air by one of three Boeing B‑29s that left Tinian in the Mariana Islands in the predawn hours of August 6, 1945, for Hiroshima. This aerial photograph is less well known, taken about one hour after the atomic bomb detonated over Hiroshima, a city the size of Houston, Texas. “Little Boy” was carried by the Enola Gay, a modified B‑29 Superfortress (a so-called “Silverplate” Superfortress configured to carry an atomic bomb) that was piloted by 30‑year-old Col. Paul Tibbets, Jr. Tibbets had developed his flying skills as a pilot for the U.S. Eighth and Twelfth Air Forces over Europe and North Africa. In March 1943 Tibbets returned to the States to test-fly the new Superfortress, earning him the nickname “Mr. B‑29.” Interestingly, it was Brig. Gen. Leslie Groves, military head of the Manhattan Project, who settled on Tibbets and the Boeing heavy bomber to deliver the coup de grâce to World War II.

![]()

Right: Nearly 11 feet long and 5 inches in diameter, “Little Boy” lies on trailer cradle before being loaded into Enola Gay’s bomb bay. The plane’s bomb bay door is visible in the upper right-hand corner of the photo. Of the 131 lb of uranium‑235 in the bomb, less than 2 lb underwent nuclear fission. The force of the explosion was roughly equivalent to 15,000 tons (15 kilotons) of TNT. (The common size today is several hundred kilotons.) Almost all of the energy was released in the initial 30 seconds after detonation: 50 percent in a pressure shock wave, 35 percent in the form of light and heat (the surface temperature of the fireball was 10,800°F, or 6,000°C, which approximates the temperature of the sun’s surface), and 5 percent in nuclear radiation. The flash of light from the blast could have been seen on a neighboring planet.

|  |

Left: The Hiroshima Chamber of Industry and Commerce Building was the only building remotely close to standing near the epicenter of the atomic bomb blast of August 6, 1945. Known today as the Genbaku (“Atom Bomb” in Japanese) Dome, it was left unrepaired as a reminder of the event. On December 7, 1996, the iconic Genbaku Dome was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List. It sits in a lush park, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, surrounded by a city of one million people. For many visitors the memorial park and museum are hallowed ground, like a cemetery, because the ashes and bones of the bombing victims are literally underfoot in a thin white layer a few feet beneath the earth’s surface. A Children’s Peace Monument in the park was unveiled on Children’s Day, May 5, 1958, to commemorate the thousands of innocent young victims, but in particular of Sadako Sasak who at age 12 died of radiation-induced leukemia 10 years after “Little Boy” was dropped on Hiroshima.

![]()

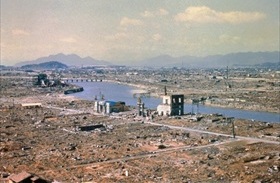

Right: Eight months after America’s ultimate weapon was dropped, Hiroshima still stands in ruins, the visible evidence of the world’s first use of nuclear weapons in war. Of the 68 cities bombed in the summer of 1945, Hiroshima was fourth in terms of square miles destroyed, 17th in the percentage of the city destroyed, but second in the number of civilian deaths.

Well-Done Documentary on the Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, August 6 and 9, 1945

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click