PRESIDENT DECLARES NATIONAL CODE TALKERS DAY

Washington, D.C. · August 14, 1982

Some 44,000 Native Americans served in the U.S. military during World War II. One-and-a-half times more Native Americans volunteered for service than were drafted; indeed, Native American participation in the war per capita exceeded any other group. Native Americans served in all theaters, but predominately in the Pacific.

No group of Native Americans has received as much fame as those from the Navajo Nation. Navajo Code Talkers played a pivotal role in every successful engagement against the enemy in the Pacific, from Guadalcanal to Okinawa. Because Navajo Code Talkers were themselves the secret code of U.S. Marines, these men—former farmers and sheepherders in the U.S. Southwest—were highly prized and often heavily guarded. From the original 29 code talkers in 1942 who developed their ingenious “secret weapon”—their 411‑word vocabulary in their native Dine tongue—at least 400 young Navajos trained as code talkers. The coded oral messages they passed between themselves were totally unintelligible to anyone else; in fact, their code was the first unbreakable code in U.S. history.

In the Battle of Saipan (June 15 to July 9, 1944), a Navajo Code Talker convinced a U.S. artillery unit in the rear that theirs was not a Japanese position on which American shells were raining (“friendly fire”) but an American one: eavesdropping Japanese had learned to perfectly imitate American radio communication between units except when it was in Navajo (Dine). During the Battle of Iwo Jima (February and March 1945), six code talkers sent and received 800 field messages working 24/7. During the war 13 Navajo Code Talkers were killed in action. After the war code talkers were forbidden to speak of their service until 1968, when the Code Talker Operation was finally declassified.

Code talkers received wide public recognition when President Ronald Reagan designated this date in 1982—the 37th anniversary of Japan’s unconditional surrender—as National Code Talkers Day. In July 2001 the original 29 Navajo Code Talkers were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal. On November 15, 2008, the Code Talkers Recognition Act of 2008 was signed into law by President George W. Bush. The act recognized every Native American code talker who served in the U.S. military during both world wars with the exception of the already-awarded Navajo. Each nation was given a Congressional Gold Medal, to be retained by the Smithsonian Institution, and a silver medal duplicate was given to each code talker.

![]()

Native Americans in World War II

|  |

Left: Navajo Code Talkers, Saipan, June 1944. Code talkers are strongly associated with bilingual Navajo speakers specially recruited by the U.S. Marine Corps to serve in their standard communications units in the Pacific Theater. The Navajos’ language, Dine, has an elaborate syntax and grammar, and the spoken word uses tones the untrained ear cannot easily distinguish. So the code the original 29 Navajo Code Talkers developed befuddled the Japanese all during the war. Actually, Choctaw Indians serving in the U.S. Army in France during World War I pioneered code talking. Other Native American code talkers were deployed by the Army during World War II, including Cherokee (European and Pacific theaters), Choctaw (European Theater), Lakota, Meskwaki (North African Theater), and Comanche (European Theater) speakers. The Marines employed Basque speakers whose language is spoken in North Central Spain and Southwestern France for code talking in areas where other Basque speakers were not expected to be operating (Hawaii and Australia).

![]()

Right: Native American women as Marine Corps Reservists at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, October 16, 1943. The three women represent the Blackfeet, Potawatomi, and Ojibwe nations.

|  |

Left: Lt. Woody J. Cochran holds a Japanese flag, New Guinea, April 1, 1943. A Cherokee from Oklahoma and a bomber pilot, Cochran earned the Silver Star, Purple Heart, Distinguished Flying Cross, and Air Medal.

![]()

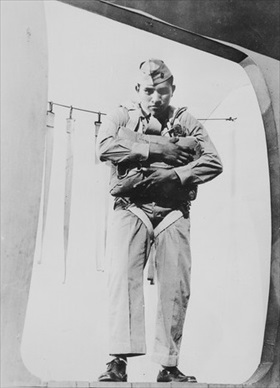

Right: Cpl. Ira Hayes was a Pima Native American from Central Arizona. At age 19, he is shown in this photo at the Marine Corps Paratroop School at Camp Gillespie near San Diego, California, in 1943. Hayes fought in the Pacific Theater and is best known for helping raise an American flag and flagstaff over Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima on February 23, 1945, an event famously photographed by Joe Rosenthal of the Associated Press.

President George W. Bush Honors 29 Original Navajo Code Talkers, July 26, 2001, in Washington, D.C.

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click