OPERATION DYNAMO TO RESCUE TRAPPED BRITISH ARMY

London, England • May 19, 1940

Following Britain and France’s declaration of war on Germany on September 3, 1939, neither of the Allies committed to launching a significant land offensive against Adolf Hitler’s Germany as punishment for the invasion of its eastern neighbor, Poland, which was in a treaty relationship with the two Western powers. The most the British were prepared to do was deploy a 315,000‑man expeditionary force, with aircraft, artillery, and tens of thousands of vehicles, to the Franco-Belgian border.

Hitler, however, was busy making preparations to end the so-called Phony War (German, Sitzkrieg; French, le drôle de guerre), as this early, quiet, and lengthy phase of World War II came to be called. His war in the West began on May 10, 1940, when Wehrmacht forces invaded the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and France. A series of Allied counterattacks failed to sever the armored German spearhead through Belgium’s Ardennes Forest, which quickly reached the English Channel, swung north along the French Picardy and Nord-Pas-de-Calais coasts, and threatened to capture the Channel ports and trap the surviving Allied troops and their heavy equipment before they could escape to England.

On this date, May 19, 1940, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered the British Admiralty to draw up a contingency plan for a seaborne rescue mission that became known as the “Miracle of Dunkirk” after the mission was launched on May 26. Rescue fleet numbers peaked at about 900 disparate vessels, ranging from British and French destroyers and other warships, Dutch fishing boats and trawlers, Belgian and even Polish watercraft, cross-Channel ferries, pleasure steamers to the fabled “little ships” such as tugboats, barges, yachts, cabin cruisers, and even dinghies manned by one (!) or more steel-nerved citizen volunteers. (“Little ships” accounted for over two-thirds of the rescue “fleet.”) Operation Dynamo, as the evacuation effort was officially known, initially targeted rescuing upwards of 45,000 members of the British Expeditionary Force. That was about one-fifth of the fighting men now hunkered down 6 miles south of the Belgian border and facing annihilation on Dunkirk’s hostile beaches. However, Operation Dynamo succeeded in bringing some 198,229 men of the BEF to safety in England along with 139,997 French troops and some soldiers from Belgium, whose army had capitulated to Germany on May 28. Troops of every nationality were given equal priority in evacuating.

Bad flying weather, Hitler’s dithering—he inexplicably ordered Gen. Wilhelm Ritter von Thoma’s panzers to halt in place on May 24 before reversing himself two days later—and Royal Air Force Spitfire and Hurricane fighters saved the nucleus of the British Army and the germ of the Free French Forces (Forces françaises libres), or FFL, from certain destruction. Flying from airfields in Southern England, RAF pilots made over 4,822 sorties between May 26 and June 4. The epic evacuation of the trapped soldiers ended on June 4 for a grievous loss of 226 vessels, most of them British (31 on June 1 alone), and 145 planes (not including the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm) out of 2,739 aircraft. German losses in air battles over Dunkirk were estimated at 132 planes, though the figure is probably too high.

Seen by Hitler, his inner circle, and the German news media as a crushing British defeat (Wilhelm Keitel, head of the Wehrmacht High Command, hailed the event as “the greatest military victory of all time” and a short time later praised Hitler as “the greatest warlord of all time”), Dunkirk (French, Dunkerque) became a major victory for British wartime morale. The Dunkirk Spirit stiffened national resolve and ended speculation over a negotiated settlement with Nazi Germany, which Hitler gambled would happen and lessen the chances of the United States, officially neutral in the conflict but increasingly collaborating with Great Britain, becoming an active belligerent. Four years later the Atlantic allies returned to the continent—to Normandy on the French coast, over 200 miles south of Dunkirk. On June 6, 1944—D-Day—the Allies were outfitted with the largest assemblage of invasion ships, aircraft, men, and equipment in history. In less than 24 hours, 176,000 British, American, and Canadian troops had disembarked from 4,000 transport ships to begin the West’s successful assault on Hitler’s “Festung Europa” (Fortress Europe).

![]()

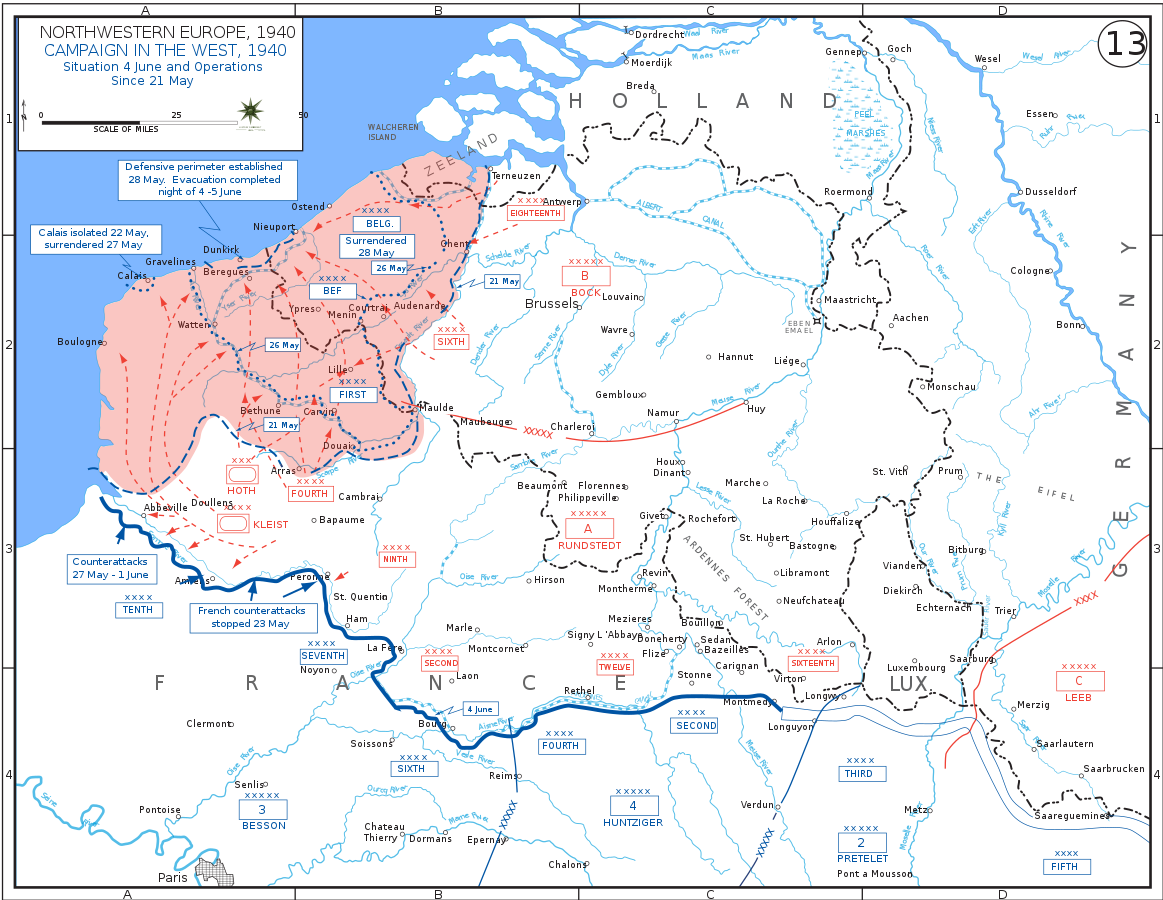

Operation Dynamo and the Rescue of the British and French Armies at Dunkirk, France’s Northernmost Point, May 26 to June 4, 1940

Above: The semicircular Dunkirk pocket, France, June 4, 1940, the last day of Operation Dynamo. (The seaside town of Dunkirk, located in a marshy area that aided in the town’s defense, is roughly halfway between the northern and southern edges of the rose-colored area of the map.) By then a second smaller pocket at Lille, held by remnants of three French divisions, had collapsed. Churchill originally described the German entrapment of the British Expeditionary Force in France as “a colossal military disaster,” what with “the whole root and core and brain of the British Army” facing capture and extermination. (Actually, the “brain” of the BEF was befuddled, handicapped by an inaccurate assessment of Wehrmacht capabilities, cunning, and ruthlessness. Not a few soldiers had little-to-no combat experience, lacked discipline and adequate training [some never even fired a shot in training], and made poor decisions when under attack.) From its desperate outset, the rescue of the BEF was fraught with peril. Following the conclusion of Operation Dynamo, Churchill hailed the BEF’s rescue as a “miracle of deliverance.” Under the codename Operation Ariel, close to another 192,000 Allied personnel and civilians, 144,000 of them British servicemen in what became known as the Second Expeditionary Force, were evacuated through other escape ports in Brittany and along the French Atlantic coast between June 15 and 25. Not only did the perilous evacuations turn a military debacle into a story of sacrifice and heroism that served to raise and sustain the morale of Britain’s wartime populace, it allowed the British Army to recuperate and rebuild itself for the task of liberating the continent four years later.

|  |

Left: A British soldier awaiting evacuation on a Dunkirk beach exchanges Enfield rifle rounds with low-flying, machine-gun strafing German aircraft. The Germans used their Luftwaffe as flying artillery (along with unloading explosive and tear gas bombs on the beaches) while their army shelled the beaches and marshy flatlands from the ground. During the Battle of France (May 10 to June 22, 1940), the British Expeditionary Force suffered 11,000 killed or missing, 14,070 evacuated wounded, and 41,030 taken prisoner. During the same period the French armed forces suffered between 55,000 and 85,000 killed, 120,000 wounded, and 12,000 missing, with at little over 1.5 million soldiers captured and taken as prisoners of war to Germany, where roughly 940,000 remained until 1945. World War I hero hero Marshal Philippe Pétain, who assumed power in France in June 1940 in the wake of his country’s military reverses, falsely blamed Britain for the collapse of the French Army and characterized Operation Dynamo as a treacherous act of desertion.

![]()

Right: A British fishing boat picks up troops off the coast of Dunkirk while a Ju 87 Stuka’s bomb explodes a few yards away. Many boats put themselves in harm’s way multiple times, and at all hours of the day and night, especially the small, shallow-draft civilian craft that navigated low tide and ferried soldiers mostly from beaches east of Dunkirk itself to larger boats and ships offshore. Some were capsized, hit by waves or swamped by desperate soldiers struggling to heave themselves into the boats. In 9 days, more than 338,000 British, Commonwealth, French, and Belgian soldiers were rescued by an armada of around 220 warships and 700 assorted “little ships” flying British, French, Dutch, and Belgian flags. On June 4 the greatest sealift rescue in military history concluded. A cinematic treatment of the epic rescue is depicted in Christopher Nolan’s 2017 Dunkirk, starring Kenneth Branagh as the stalwart pier master at Dunkirk Harbor, Commander Bolton, a composite of several Royal Navy officers during the Allied evacuation.

|  |

Left: A column of British soldiers wades from Dunkirk’s popular resort beachfront through ocean shallows to board waiting vessels. Many of the approximately 198,229 men of the BEF who were rescued stood for hours shivering in shoulder-deep water, exhausted, fearful, thirsty, and hungry, easy targets for German aircraft bombs and long-range artillery shells. Contrary to myth, two-thirds of the fighting men evacuated from Dunkirk departed, not from beaches, but from the wrecked harbor area on a breakwater surfaced with wooden planks and called a mole. Despite the remarkable efficiency and success of the rescue operation itself, all kit, heavy equipment, and vehicles had to be left behind: 2,300 artillery pieces, 500 antitank guns, 600 tanks, almost 65,000 vehicles, and 20,000 motorcycles—practically half of the British Army’s entire inventory of heavy weaponry. More than 75,000 tons of ammunition and 162,000 tons of fuel were also abandoned. Hitler’s Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (high command) considered the British incapable of defending themselves—outgunned and outnumbered, at least for the near term, by Germany’s armed forces. So the Fuehrer directed preparations be made for Unternehmen Seeloewe (Operation Sea Lion), the amphibious cross-Channel invasion of the British Isles planned for late-September 1940.

![]()

Right: A wounded French soldier being brought ashore on a stretcher at Dover, England, the main reception port for evacuees. (Dover was 20 miles from the French coast.) Of the more than 100,000 soldiers from three French armies who escaped from Dunkirk, only about 3,000 chose to join Charles de Gaulle’s Free French Forces in London. (In his memoirs De Gaulle claims he could have recruited many more to his Free French army had British authorities given him free rein to seek recruits among French evacuees in Britain.) The rest of the rescued French soldiers were repatriated back to Brest, Cherbourg, and other French ports in Normandy and Brittany, where roughly half of them were redeployed against the invading Germans.

|  |

Left: British troops evacuating to ship via a lifeboat bridge. The British Ministry of Shipping telephoned boat builders around the English coast, asking them to collect all boats with shallow draft that could navigate the waters off Dunkirk’s beaches. Nineteen lifeboats of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution sailed to Dunkirk as part of the relief flotilla.

![]()

Right: French troops rescued by a British ship at Dunkirk. Between 30,000 and 40,000 French troops were captured in the Dunkirk pocket. For many French soldiers who were repatriated to France, their escape from Dunkirk was not a salvation, but represented only a few weeks’ hiatus before being made prisoners of war by the German Army following the Franco-German armistice of June 22, 1940.

Contemporary Newsreel of Operation Dynamo, the Allied Evacuation of the Dunkirk Pocket, May 19 to June 4, 1940

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click