JAPANESE SEIZE RABAUL, AUSSIE ISLAND OUTPOST

Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia · January 23, 1942

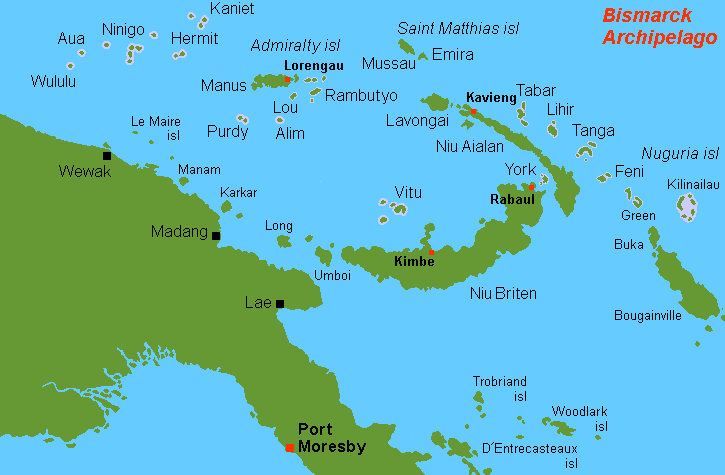

On this date in 1942, over a month after Pearl Harbor, 20,000 Japanese Marines quickly overran the Australian garrison at Rabaul, New Britain, the largest island in the Bismarck Archipelago (labeled “Niu Briten” on map below). Rabaul’s capture was important because of its proximity to the Caroline Islands to the north, site of a major Japanese naval base on Truk. Soon afterwards Rabaul became the principal strategic center for Japanese air and naval forces in the Southwest Pacific. The island served as the key point for the failed Japanese invasion of Port Moresby (May–November 1942), the capital and largest population center of Papua New Guinea. As the Allies wound down their Guadalcanal campaign (August 7, 1942 to February 9, 1943), they recognized that recapturing Rabaul, with its 100,000 enemy soldiers and naval personnel, reinforced by 600 planes, tanks, artillery, and other supplies, would require more resources than they had at their command—a minimum of five extra divisions and almost 2,000 planes. However, at the opposite (western) end of the island, where the Japanese were in possession of two airstrips, U.S. Marine and army units swarmed ashore to capture the airfields they believed would assist them in their planned attack on the Rabaul stronghold. The Battle of Cape Gloucester (December 26, 1943 to April 22, 1944), part of Operation Cartwheel, a mixed land, sea, and air operation in the Southwest Pacific (1943–1944), was said by veterans to have been “worse than Guadalcanal.” The troops got bogged down in swampy terrain and thick jungle, where the chief enemy was Mother Nature. By this time, however, Rabaul had been effectively neutralized by heavy Allied bombardment, with over fifty Japanese ships and planes sent to the bottom of the harbor there. Because it no longer posed a threat and because of the perceived difficulty in capturing it, war planners wisely decided to “island hop” past Rabaul to attack more lightly defended islands, sparing themselves another Iwo Jima or Okinawa. So impregnable were the Japanese at Rabaul that it took nearly two years to evacuate all their troops after the war.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0688016200,0760332967,1456593226,145165913X,0451232267,0760345597,0140246967,1578066646,0764302272,0425257827″ /]

Battle of Cape Gloucester, December 26, 1943 to April 22, 1944

|

Above: Location of Rabaul and the island of New Britain (“Niu Briten”) in the Bismarck Archipelago, Southwest Pacific. Cape Gloucester (also known as Tuluvu), which is on the western tip of New Britain, does not appear on this map.

|  |

Left: Men and cargo of the 1st Marine Division, veterans of the campaign on Guadalcanal (August 7, 1942 to February 9, 1943), are pictured aboard a landing craft for the invasion of Cape Gloucester, December 1943. Cape Gloucester, December 1943. Cape Gloucester was located on the northern side of the far west of the island of New Britain.

![]()

Right: The initial landings at Cape Gloucester had as their main objective the isolation of Rabaul, 300 miles to the east on the other side of the island. The plan called for the Allies to secure Cape Gloucester’s beachheads and capture the dual airfields to assist in planned attacks on the Japanese garrison at Rabaul. The Marines took the airfields on December 30, 1943, after slogging for three days through neck-deep swamps (marked “Damp Flats” on their maps), where men were actually killed by sodden branches falling from rotting trees. Impeded by heavy rains, Army aviation engineers worked around the clock to make Airfield No. 2, the larger of the airstrips, operational, a task that took them until the end of January 1944. In the end the two airstrips proved of marginal value to the Allies.

|  |

Above: Embattled Marines at times could see no more than a few feet ahead of them owing to the thick jungle (left frame). Retreating at first into the jungle of Cape Gloucester, Japanese soldiers finally gathered strength and counterattacked their Marine pursuers. The photo in the right frame shows Marines in the forest’s darkness fending off a Japanese attack using an M1917 Browning machine gun. Marines needed three weeks of hand-to-hand combat to clear more than 10,000 enemy troops from the immediate area around Cape Gloucester. The Cape Gloucester base effectively bottled up the 135,000 Japanese troops at Rabaul, because the dense, jungle-swathed mountain ridges of the interior were impassable.

|  |

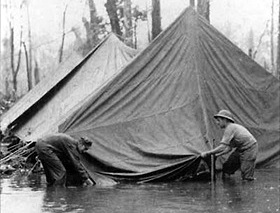

Left: Atrocious weather in the “green inferno” of New Britain proved to be the main problem for Marines and soldiers at Cape Gloucester. Monsoon deluges—as much as 16 inches of rain fell in a day—flooded foxholes and made life miserable in the base camp. Wet uniforms never really dried, and the men suffered continually from fungus infections, the so-called jungle rot, which readily developed into open sores. Mosquito-borne malaria threatened the health of the men, who also had to contend with other insects—”little black ants, little red ants, big red ants” on an island where “even the caterpillars bite.”

![]()

Right: Movement on foot or by vehicle through the island’s swamp, jungles, and tall, coarse kunai grass verged on the impossible, especially where monsoon rains had flooded the land or turned the volcanic soil into slippery mud.

“Rings Around Rabaul.” Victory at Sea Episode Makes Excellent Use of Japanese and American Footage

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click