JAPAN DELIVERS FINAL PEACE OFFER TO U.S.

Washington, D.C. • November 20, 1941

On this date in 1941 in Washington, Japanese ambassador Kichisaburō Nomura presented his government’s final proposal for peace in the Asia Pacific region. Through much of 1941, Ambassador Nomura had negotiated with U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull to resolve festering bilateral issues. Chief among the issues were the Japanese conflict with China, where Japan had been engaged in an intractable war since 1937 from which it could extract neither victory nor a face-saving withdrawal; the Japanese occupation of Vichy French Indochina (since September 1940); and the United States oil embargo against Japan (since the summer of 1941).

The U.S., Nomura told State Department officials, must restore normal trade relations with Japan, unfreeze Japanese financial assets in the U.S., discontinue military and economic aid to Chiang Kai-shek’s Chinese government, and give Japan a free hand in China. Also, the U.S. must recognize the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, a Japanese euphemism for the rich mineral and agricultural resources in Southeast Asia controlled by the Western colonial powers—the U.S., Britain, the Netherlands, and Vichy France. The State Department’s response on November 26 was for Japan to withdraw its troops from China and sever its Tripartite Treaty ties with Germany and Italy as a condition for peace.

On the same day as the State Department issued its response to the Japanese negotiators, the War and Navy departments updated their own commands. Army Chief of Staff Gen. George Marshall warned: “Negotiations with Japan appear to be terminated [for] all practical purposes. . . . Hostile action [is] possible at any moment.” Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Harold Stark warned that “an aggressive move by Japan is expected within the next few days,” possibly against American interests in the Philippines, British holdings on the Malay Peninsula and Singapore, and Thailand. Marshall said that if hostilities could not be avoided, Japan would have to make the first move.

The fruitless diplomatic negotiations between the U.S. and Japan in Washington were a sideshow. On November 18 the Japanese parliament, pushed by Prime Minister and Army Minister Gen. Hideki Tōjō, had approved a resolution of hostility against the U.S. The following week, on November 26, over 30 vessels of the Japanese First Air Fleet, among them six aircraft carriers, under the command of Vice Adm. Chūichi Nagumo left Japanese waters (Kurile Islands) on a 3,400‑mile journey to attack the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, home of the American Pacific fleet. The massive surprise attack on Sunday morning, December 7, 1941, was a stunning tactical victory for the Japanese aggressor, but one that spelled Japan’s doom, as well as that of its militaristic and nationalist leader Tōjō. After that country’s unconditional surrender in September 1945, Tōjō was tried by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East for war crimes, found guilty, and hanged at Sugamo Prison outside Tokyo, along with six other convicted Japanese war criminals, on December 23, 1948.

![]()

On the Road to Pearl Harbor

|

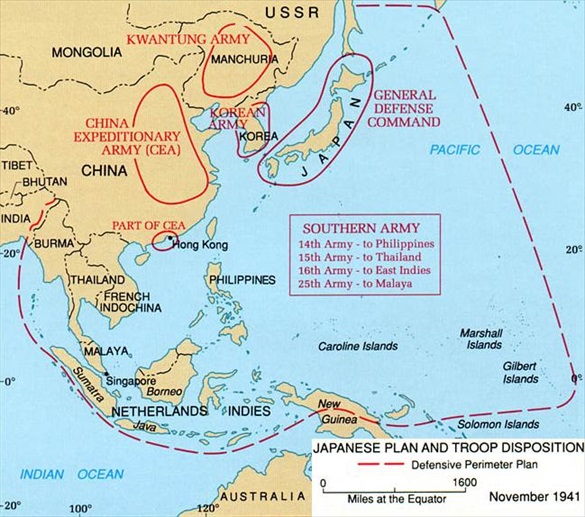

Above: November 1941 map of Japanese plans and troop dispositions. Nations within the map’s boundaries were also integrated into a Japanese-led order, the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere launched on June 29, 1940. Member states would supposedly share prosperity, peace, and a new cultural identity free from Western colonialism and domination (“Asia for Asiatics”). However, partly because the Japanese directed that economies within the Co-Prosperity Sphere be managed strictly for the production of raw materials related to the war effort and partly because of Japanese racial attitudes toward populations in the occupied countries, neither “co-prosperity” nor pan-Asianism emerged among its eleven member states.

|  |

Left: Japanese Ambassador retired Adm. Kichisaburō Nomura (left) and Special Envoy Saburō Kurusu (right) met Secretary of State Cordell Hull (center) several times before (and during!) the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Nomura’s repeated pleas to his superiors in Tokyo to offer the Americans meaningful concessions were rejected by his government. When Special Envoy Kurusu (Japan’s ambassador to Hitler’s Germany from 1939 to November 1941) reviewed President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s demands for peace in Asia on November 26—by coincidence the same day the Japanese First Air Fleet set steam for Pearl Harbor—Kurusu replied, “If this is the attitude of the American government, I don’t see how an agreement is possible. Tokyo will throw up its hands at this.” In his memoirs Hull credited Ambassador Nomura with having been sincere in trying to prevent war between Japan and the United States. In Kurusu’s 1952 memoir, The Desperate Diplomat, the special envoy professed his total lack of knowledge regarding the pending Pearl Harbor attack. Indeed, Kurusu continued to pursue his peace efforts right up to Japan’s August 1945 capitulation.

![]()

Right: Nomura (left) and Kurusu after meeting President Roosevelt at the White House on November 17, 1941. Secretary of State Hull brought the special envoy to the Executive Mansion to meet with the president after Kurusu had come with his government’s last peace offer. Twenty days later on the afternoon of December 7 (2 p.m. Washington time), Kurusu delivered Japan’s reply to the Roosevelt administration’s counter demands, breaking off relations and closing with the statement that “The immutable policy of Japan is to promote world peace.” Unaware of what was happening at that very hour in Hawaii (though the president, Hull, and Navy Secretary Frank Knox knew), Kurusu and Nomura were questioned by news reporters as they left Hull’s office. “Is this your last conference?” one asked, and an unsmiling Nomura had no answer. “Will the embassy issue a statement later?” asked another, and Kurusu replied, “I don’t know.”

|

Above: Former Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tōjō (rear in glasses with headphone) was tried by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (January 1946 to November 1948) for war crimes and found guilty of waging wars of aggression (five counts), waging unprovoked war against the Republic of China (one count), and ordering, authorizing, and permitting inhumane treatment of prisoners of war and others (one count). He accepted full responsibility in the end for his actions during the war.

“War Comes to America: America Attacked,” Part of Frank Capra’s “Why We Fight” Series

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click