HIROHITO AGREES TO WAR WITH U.S.

Tokyo, Japan · November 5, 1941

Early in September 1941 Japanese officials gave their diplomats until October to reverse the policy of the Western powers—principally the U.S., Great Britain, and the Netherlands—of restricting Japan’s access to vital Southeast Asian resources, among them oil, rubber, tin, timber, and rice. The restrictions had been imposed the previous month after Japan had stationed troops in Vichy French Indochina. For its part, the U.S. had frozen Japanese assets in the U.S. and embargoed oil and gasoline exports to Japan. At an Imperial Conference of Japanese officials (Gozen Kaigi) attended by Shōwa Emperor Hirohito on this date in 1941, Gen. Hideki Tōjō—war minister, home minister, and since October 17 prime minister as well—said Japan must be prepared to go to war with the West, with the time for military action tentatively set for December 1 if diplomacy with the U.S. and European colonial powers failed to improve relations and reverse trade sanctions. The Japanese foreign minister didn’t see that happening, telling the august assembly that the prospects for diplomatic success are, “we most deeply regret, dim.” Hirohito, who two days earlier had been briefed about the planned attack on U.S. military installations at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, readily assented to the operations plan for war against the Western nations. He held meetings with Tōjō and the military leadership until the end of November. Meanwhile the Japanese Diet (parliament) approved a resolution of hostility against the U.S. Late that month Kichisaburō Nomura, Japan’s ambassador to Washington, failed to overcome President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s insistence that Japan must withdraw from China and stop its aggressive Southeast Asian incursions before the U.S. would resume trade with his country. On December 1, another Imperial Conference officially sanctioned war against the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands. Continued talks in Washington to heal the breach between the two nations were a smokescreen for Vice-Adm. Chūichi Nagumo’s Striking Force (Kido Butai) of six aircraft carriers as they made their way to the Hawaiian Islands by a little-used route and took up positions on December 4, 1941, 250 miles northwest of their designated targets: the U.S. Pacific Fleet riding at anchor at Pearl Harbor and U.S. aircraft parked smartly at Hickman Field.

![]()

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0307594017,0060931302,0842051538,1595554572,1591145201,161200010X,046503179X,0801495296,0823224724,082481925X” /]

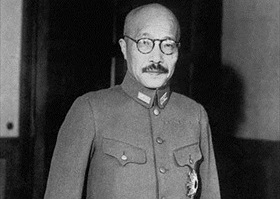

Emperor Hirohito and His Wartime Prime Minister, Gen. Hideki Tōjō

|  |

Left: Soldiers parade before Shōwa Emperor Hirohito, a revered symbol of divine status. While perpetuating a cult of religious emperor worship, Hirohito also burnished his image as a warrior in photos and newsreels riding Shirayuki (White Snow), his beautiful white stallion. One news agency reported that Hirohito made 344 appearances on Shirayuki.

![]()

Right: Shōwa Emperor Hirohito, seated in middle, as head of the Imperial Conference (Gozen Kaigi), January 1, 1945. Convened by the Japanese government in the presence of the Emperor, the Imperial Conference was an extraconstitutional conference that focused on foreign affairs of grave national importance. Hirohito was also a member of the Imperial General Headquarters-Government Liaison Conference. The Liaison Conferences coordinated the wartime efforts between the Imperial Japanese Army and Imperial Japanese Navy. In terms of function, it was roughly equivalent to the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. The final decisions of Liaison Conferences were formally disclosed and approved at Imperial Conferences over which the Emperor presided in person.

|  |

Left: Defendants at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (1946–1948). Gen. Hideki Tōjō (1884–1948), former war minister and prime minister of Japan, is fifth from left in first row of the defendants’ dock. Alluding to Emperor Hirohito’s success in dodging indictment as a war criminal, Judge Henri Bernard of France concluded that the war in the East “had a principal author who escaped all prosecution and of whom in any case the present Defendants could only be considered as accomplices.”

![]()

Right: Tōjō in military uniform. On July 22, 1940, Tōjō was appointed Army Minister. During most of the Pacific War, from October 17, 1941 to July 22, 1944, he served as Prime Minister of Japan. In that capacity he was directly responsible for the attack on Pearl Harbor. After the war Tōjō was arrested, sentenced to death for war crimes during the Tokyo Trials, and was hanged on December 23, 1948.

Part I of BBC Documentary on Emperor Hirohito’s Role in Japanese Aggression in World War II

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click