FOREIGN NATIONALS CREATE NANKING SAFETY ZONE

Nanking, China • November 22, 1937

On this date in 1937 in Nanking (today’s Nanjing), China’s capital at the time, fifteen foreign businessmen, missionaries, and journalists under the leadership of German national and Nazi Party member John Rabe organized the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone. The mission of the committee was to shelter Chinese refugees against the looming Japanese assault on the city, which had a prewar population of between 200,000 and 250,000. The Japanese had laid siege to the coastal city of Shanghai (they would enter that city on November 26) and had begun bombing the terrified inhabitants of Nanjing, nearly 200 miles inland, in August.

When Nanjing fell on December 13, the Nanking Safety Zone housed over 250,000 refugees in refugee camps that could fit inside the area of New York City’s Central Park (3.5 sq. miles). These refugees were mostly spared the incredible violence and brutality inflicted on Nanjing’s population and their city over a period of three months (December 10, 1937, to February 10, 1938). Historians, period film and photographs, and eyewitness accounts of Westerners, Chinese, and Japanese (Rabe and others kept detailed diaries) agree that tens of thousands of Chinese women, men, and children were raped, sometimes gang-raped in public streets, and 370,000 or more civilians and surrendered soldiers perished in what became known as the Nanking Massacre, or the Rape of Nanking.

Reputedly 57,500 Chinese POWs were shot and individually bayoneted on December 18, 1937, in the Straw String Gorge Massacre, their bodies mostly dumped into the Yangtze River, after Emperor Hirohito (ironically, the name Hirohito means “abundant benevolence”) had personally approved removing the constraints of international law the previous August on the treatment of Chinese ensnared in “military operations.” The Emperor advised his staff officers to stop using the term “prisoner of war” so that Chinese captives could be “lawfully” executed.

In 1946 the Chinese Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek established the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal to try Japanese Army officers accused of war crimes. Two former lieutenants were convicted of taking part in the infamous Nanjing contest to kill 100 people using a sword. Hundreds of survivors as well as several foreigners who had witnessed the monthslong atrocity from their refuge in the Nanking Safety Zone provided testimony to convict Lt. Gen. Hisao Tani, whose superior officer in Nanjing, Iwane Matsui, had been tried by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo and hanged as a war criminal. Tani’s guilty verdict corroborated the records of Rabe and his Nanking Safety Zone committee.

![]()

![]()

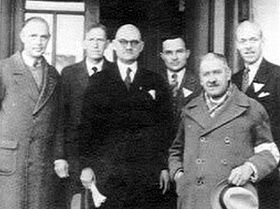

John Rabe and the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone (November 1937 to February 1938)

|  |

Left: John Rabe (center in photograph) was elected chairman of the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone, partly owing to his status as a member of the Nazi Party and to his country’s membership in the German-Japanese bilateral Anti-Comintern Pact (November 25, 1936). Rabe, his zone administrators, and other refugees from foreign countries frantically tried to protect Chinese civilians from being killed by unrestrained Japanese soldiers (some who went from house to house in search of young girls) and to halt the wholesale rape, mutilation, looting, and burning. Owing to their efforts, between 250,000 to 300,000 Chinese were protected inside the Nanking Safety Zone or managed to escape the city during the two-month-long massacre.

![]()

Right: In China since 1908, Rabe had moved into the top slot of Siemens China Corporation. In this photograph he is seen in his underground office on the grounds of his home during the period of the Nanking Massacre (December 10, 1937, to February 10, 1938). The sign says his office hours are from 9 p.m. to 11 p.m.

|  |

Left: Rabe opened up his home and garden to shelter 650 more refugees from the carnage outside the Nanking Safety Zone. In his diary Rabe wrote that from time to time Japanese soldiers would enter the zone, carry off a few hundred men, women, and children, and either summarily execute them or rape and then kill them. Between mid-December 1937 and February 5, 1938, the Nanking Safety Zone Committee forwarded to the Japanese embassy a total of 450 cases of murder, rape, and general disorder by Japanese soldiers in Nanjing.

![]()

Right: The former residence of John Rabe located in the then Nanking Safety Zone. On February 18, 1938, the Nanking Safety Zone International Committee was forcibly renamed “Nanking International Rescue Committee,” and the Safety Zone effectively ceased to function. Ten days later Rabe left Nanjing for Germany. With him he took a large number of source materials documenting the atrocities committed by the Japanese in Nanjing. On returning home he showed films and photographs of Japanese atrocities in lecture presentations and even wrote to Adolf Hitler, asking him to use his influence to persuade the Japanese to stop further inhumane violence. By the time of his death from a stroke in 1950, Rabe had amassed more than 2,000 pages of his and other foreigners’ eyewitness reports, newspaper articles, radio broadcasts, telegrams, and photographs of the atrocities, all meticulously typed, numbered, bound, and illustrated.

Nanking Massacre, 1937: Japanese Aggression in China (Contains Scenes of Violence and Gross Brutality)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click