BRITISH NAVY ENJOYS CAPITAL VICTORY AT TARANTO

Alexandria, Egypt • November 11, 1940

Italian Army operations in North Africa, based in Libya, required a supply line from the Italian mainland. The British Army’s North African Campaign, based in Egypt, suffered from supply difficulties in the Mediterranean Theater due to the proximity of Italy’s Regia Marina naval base at Taranto on the Italian “heel.” Taranto was home port to 6 battleships, 7 heavy and 2 light cruisers, and 28 destroyers that bristled with more than 700 antiaircraft guns. The naval base itself was well protected by 13 large listening devices (no radar) that could detect aircraft from miles away, 21 batteries of 4-inch antiaircraft guns, 84 automatic cannons, more than 100 light machine guns, and 22 powerful searchlights to blind incoming pilots during night attacks. Adding passive devices to harbor defenses were 87 barrage balloons and 2.6 miles of anti-torpedo nets deployed around some of the ships.

On this date, November 11, 1940, and the next citizens in Great Britain received cheering news. The carrier HMS Illustrious based in Alexandria, Egypt, had launched the first all-aircraft, ship-to-ship naval attack in history, crippling Benito Mussolini’s fleet at Taranto for the loss of two aircraft, two killed, and two captured. Just two waves of obsolescent Fairey Swordfish biplane torpedo bombers had severely damaged or sunk half of Italy’s battleships in one night, shifting the balance of power in the Mediterranean Theater in favor of the Allies. Bad weather the following night prevented the Illustrious from launching another raid on the remaining ships in Taranto’s harbor, though the Regia Marina had begun hastily transferring its undamaged battleships, cruisers, and destroyers from Taranto to Naples, on Italy’s west coast, to protect them from similar attacks.

The devastation inflicted by 21 British torpedo bombers on the Italian battle fleet was the beginning of the rise of naval aviation over the big guns of battleships, a lesson not lost on the Japanese, who flew an assistant naval attaché from Berlin to Taranto to investigate and report back on the attack firsthand. Among the people the naval attaché spoke with was Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, who led the December 7, 1941, attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

(Interestingly, a U.S. Navy observer, Lieutenant Commander John Opie III, was aboard the HMS Illustrious to witness the Taranto strike and report back what he learned. The Royal Navy, he reported on November 14, 1940, now favored air-dropped torpedoes over high-level aerial bombing. From Opie and front-page newspaper headlines senior U.S. naval commanders were well aware of the Taranto strike and the danger a similar strike posed to the Pearl Harbor naval base. Memos and reports advocating improvements to the island’s defenses languished in bureaucratic la-la land. Sadly, Opie’s request to visit Pearl Harbor and recount his “war experiences and how to train to meet the lessons learned” fell on deaf ears. Unlike the Japanese, senior U.S. Navy brass failed to make a Taranto-Pearl Harbor connection.)

Three weeks later, on December 9, Britain’s desert forces, led by the one-eyed Gen. Archibald Wavell, launched Operation Compass (December 1940 to February 1941), a dramatic thrust into Italian-held Libya against much superior enemy forces. With the Italian Navy momentarily hobbled, distracted by salvage work, or holed up in ports further up the Italian boot, Wavell’s units achieved extraordinary success, driving hundreds of miles westward, and securing 130,000 Italian prisoners. For the British people, smarting from the nightly Blitz inflicted by Hermann Goering’s Luftwaffe, the good news from Italy and North Africa brought some comfort to a grim Christmas season. If Britain’s political and military leaders were still at a loss how to win the war against Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, it seemed enough to have avoided absolute defeat in 1940.

![]()

One-Hour Battle of Taranto (Operation Judgment), the British Strike Against the Italian Naval Base at Taranto, November 11–12, 1940

|  |

Left: At 10:40 p.m. on November 11, 1940, 12 British Swordfish torpedo bombers operating from the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious in the Ionian Sea some 170 miles off the Italian coast attacked the Regia Marina (Italian Navy) at Taranto in Southern Italy, hitting the battleships Conte di Cavour of World War I vintage and the recently completed Littorio, which sustained three aerial torpedo hits. A second wave of Swordfish sank the World War I battleship Caio Duilio, which also received three torpedo hits, causing extensive damage requiring five months of repairs, the same number of months it took to bring the Littorio back into service. Two unexploded bombs hit the cruiser Trento and the destroyer Libeccio. Near misses damaged the destroyer Pessagno. Italy’s flagship battleship with it nine 15‑in cannons, the Vittorio Veneto commissioned six months earlier, was lucky to have escaped the single aerial torpedo meant for its destruction. Additionally, substantial damage was inflicted on the main Italian dockyard, nearby oil-storage facility, and seaplane base. The crippling air drop of bombs and torpedoes on the Italian naval port left 85 dead, including 55 civilians, and injured more than 581. A little over a year later, on December 19, 1941, the Italians revenged themselves when frogmen riding midget submarines planted limpet mines that badly damaged two British battleships docked at Alexandria.

![]()

Right: Affectionately called “Stringbag” (a kind of British shopping bag), the Fairey Swordfish was a torpedo bomber biplane used by the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm during World War II. By 1939 the slow (cruising speed of less than 100 mph), canvas-covered Swordfish was already outdated, yet it remained in front-line service for the duration of the war, outliving several types intended to replace it. Not only did the biplane achieve fame at Taranto in November 1940, but it famously crippled the German battleship Bismarck, which was scuttled in the North Atlantic on May 27, 1941, following incapacitating battle damage inflicted by ships of the Royal Navy.

|  |

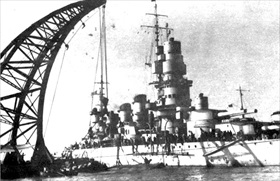

Left: The semi-submerged battleship Conte di Cavour after the attack on Taranto. A single torpedo from a Swordfish tore a 27‑ft hole in the ship close to her bow and below the waterline, killing 17 crewmen. To avoid sinking in deep water, the ship was brought into shallow water, where she settled on the bottom. The Conte di Cavour was subsequently raised and was still undergoing repairs in Trieste when Italy switched sides following the September 8, 1943, armistice with the Allies, so she never returned to service.

![]()

Right: The battleship Caio Duilio undergoing repair work after the Taranto raid. The ship was hit around midnight on November 11, 1940, by a single torpedo. The explosion caused a 36‑ft hole in the forward magazine and killed three sailors. In the early hours of November 12, the ship was run aground in shallow waters. After undergoing further repairs in Genoa, the battleship was returned to service escorting convoys headed for Libya. After the September 1943 armistice, her crew surrendered her to the Allies on Malta.

One-Hour Battle of Taranto (Operation Judgment), the British Strike Against the Italian Naval Base at Taranto, November 11/12, 1940

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click