B-17 FLYING FORTRESS MAKES COMBAT DEBUT

London, England • July 8, 1941

On this date in 1941, five months before the United States was drawn into World War II, the Boeing B‑17 Flying Fortress was flown in combat for the first time, this by the Royal Air Force in an attack on the North German port of Wilhelmshaven. The first production model, the Boeing B‑17B, was flown on June 27, 1939, and by year’s end 25 of these high-performance, four-engine heavy bombers were in America’s air fleet. By the end of World War II, nearly 13,000 “Forts” would see service in the RAF and U.S. Eighth, Ninth, Twelfth, and Fifteenth Army Air Forces.

The later-model B-17s—there were six in all—had a top speed of just under 300 mph, a range of 2,000 miles, and carried a 10- or 11‑man crew. Flying at altitudes up to 30,000 ft where temperatures were –50°F, their gutsy crewmen wore oxygen masks and an electrically heated combination of leather flight suits, boots, gloves, and googles. Like the twin-tailed Consolidated B‑24 Liberator and the British-built Avro Lancaster, the B‑17 was at the heart of the Anglo-American strategic bombing campaign in Nazi-occupied Europe. According to a statement by the U.S.-British Combined Chiefs of Staff in January 1943, the objective of the strategic bombing campaign was to destroy and dislocate the Axis “military, industrial, and economic system, and [undermine] the morale of the people to a point where their capacity for armed resistance is fatally weakened.” This strategy had widespread appeal especially in the run-up to D-Day, June 6, 1944, when the Western Allies were marshaling their strength for a full-scale ground invasion of Northwestern Europe, the prelude to their invasion and conquest of Nazi Germany.

In carrying out its role, the heavy defensive armaments of the B‑17 limited bomb loads to 2-1/2 tons per plane, which meant that raids over Axis-occupied Europe consisted, on any single mission, of hundreds and later several thousand of these warbirds, accompanied by a thousand-fighter escort. The bombers carried a deadly mix of high-explosive bombs and incendiary bombs that devastated not just population centers like Hamburg (mid-1943) and Berlin (a turnabout on the London Blitz of 1940–1941) but also key economic and military chokepoints; for example, classification/marshalling yards where troop and freight/goods cars were formed into trains, rail lines, highways, and bridges; aircraft and armament factories; ball bearing plants; and oil and artificial fuel refineries and tank farms. Tragically, an estimated 15 percent of all ordinance dropped by Allied bombers failed to explode, providing a hazard to citizens more than seven decades later.

The theory that round-the-clock bombing by the RAF (by night) and the USAAF (by day) would seriously undermine Germany’s defenses, devastate the German economy and workforce, demoralize civilian morale, and force the country’s leadership to the negotiation table like it did Italy (more or less)—all without a bloody ground invasion—did not materialize. But applied to Japan’s Home Islands, the theory worked up to a point, nudged in the end by two nuclear bombs.

Allied Heavy Bombers Over Germany and Their Escorts

|  |

Left: A B-17 Flying Fortress of the U.S. Eighth Air Force stationed at RAF Bassingbourn near Cambridge, England. Unable to conduct ground operations on the European continent until Allied strength was sufficient for a full-scale invasion, British and American war planners based their grand strategy on a protracted campaign of aerial bombardment of Germany’s industrial sites and civilian areas in order to bring the Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich to its knees. Flying in mutually supportive tight formations that enhanced protection against enemy fighters, Allied heavy bombers carrying several tons of high-explosives apiece proved devastatingly effective in combination with night-navigation and precision-bombing techniques. Of Germany’s 25 largest population centers (half-million or more residents) Leipzig suffered the least (at 20 percent) and Bochum the most (83 percent). Hamburg was 75 percent destroyed, the ill-fated target of Operation Gomorrah in 1943; Mainz, Duesseldorf, Cologne, Hannover, and Mannheim suffered 60 percent or better; and a third of the Nazi capital, Berlin, an area of 1,600 sq. miles, lay in ruins at war’s end.

![]()

Right: Three RAF Avro Lancaster B.Is based at Waddington, Lincolnshire, fly above the clouds, September 29, 1942. Introduced into service in February 1942, 7,377 of these four-engine “Lancs” were built. They became the main heavy bomber used by the RAF as well as the most famous and successful of the war’s night bombers in contrast to the USAAF heavy bombers that were used mostly in daylight raids over occupied Europe.

|  |

Left: First flown on May 6, 1941, 15,660 of these Republic P‑47 Thunderbolt air combat, ground attack, and bomber escorts were built. Rugged and armed with eight .50 caliber machine guns, these jug-shaped fighters were powered by a Pratt & Whitney R‑2800 radial engine for a maximum speed of 433 mph at 30,000 ft. They were a good match for the Luftwaffe’s Messerschmitt Bf 109s and Focke-Wulf Fw 190s. But even outfitted with extra fuel in belly tanks, P‑47s in their escort role could only accompany Allied heavy bombers from England to the German border before they were forced to turn back for home.

![]()

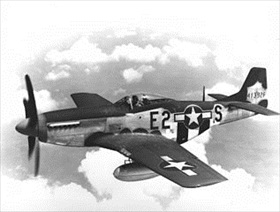

Right: North American P-51 Mustangs were used in air combat, ground attacks, precision bombing, and long-range bomber escort service. Over 15,000 P‑51s in 12 major production variants were built. The P‑51 entered service at the end of 1943. Equipped with a Rolls-Royce Merlin V engine that could propel it at 441 mph at 29,000 ft, the P‑51 and the Lockheed P‑38 Lightning virtually swept the Luftwaffe from the sky in time for June 1944’s Normandy landings. In this photo the P‑51 is wearing its Normandy invasion stripes. P‑51s destroyed 4,950 enemy aircraft in the air, more than any other fighter in Europe.

U.S. Air Force’s Presentation of the Schweinfurt and Regensburg Raids, August 17, 1943

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click